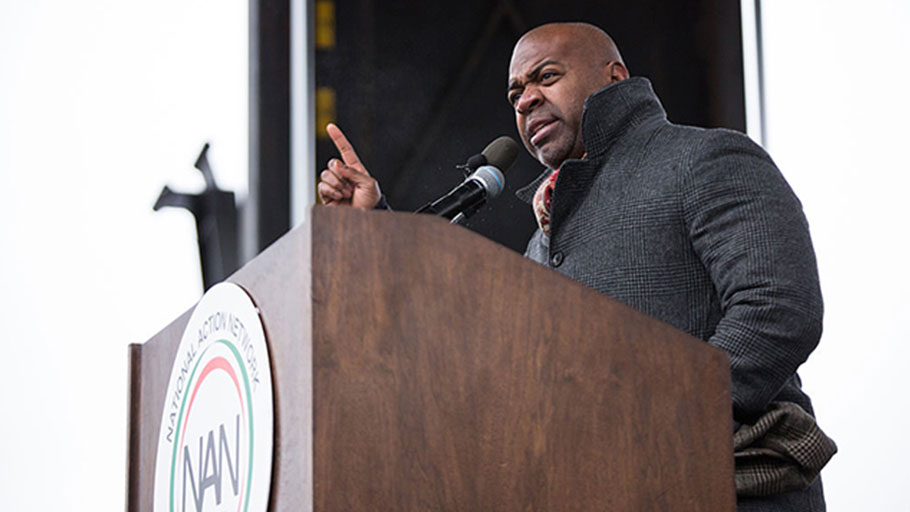

On Saturday, January 14, 2017, in Washington, DC, Ras J. Baraka, Mayor of Newark, New Jersey, addresses the crowd at the We Shall Not Be Moved march. (Photo: Cheriss May / NurPhoto via Getty Images)

By Nishani Frazier, Truthout —

On November 7, Detroit’s Coleman Young II may join the new pantheon of elected or soon-to-be elected Black mayors. This group’s uniqueness lies not in their race per se, but in their willingness to defy the Obama-era neoliberal, post-racial orthodoxy about municipal economic development. These new Black mayors are a resurgence of the old mixed with the sophisticated new. They are Black Political Power, 2.0.

If the analogy seems exaggerated, it bears noting that three of these elected or upcoming Black mayors have direct lines to 1960s Black Power. Ras J. Baraka, Newark’s mayor, is the well-known son of famed poet and activist Amiri Baraka. Baraka gained fame as one of the key writers of the 1960s Black Arts Movement and as co-chair for both the 1967 Black Power Conference and Gary Convention. Chokwe Antar Lumumba, the “radical” mayor from Jackson, Mississippi, was elected to fill the position his father held for a tragically short eight months before his untimely death in office. The elder Lumumba had a long history of activism as a member of the Republic of New Afrika. And of course, there is Coleman Young II, son to none other than Detroit’s first elected Black Mayor Coleman Young, who rode an initial wave of Black electoral success in the 1960s and 1970s.

These are not isolated cases, but instead signal a larger movement afoot. A growing body — including mayoral candidate Farad Ali of Durham, North Carolina; newly elected Mayor Randall Woofin of Birmingham, Alabama; mayoral candidate Charles Francis in Raleigh, North Carolina; Mayor Sylvester Turner in Houston, Texas; 27-year-old Stockton, California, Mayor Michael Tubbs; and more — find themselves locked in a similar battle that beleaguered local Black politicians during the 1970s. And it is not just men. Black women are also joining the struggle, including Compton, California’s youngest elected mayor, Aja Brown; Atlanta candidate Keisha Bottoms; my former Miami University colleague Yvette Simpson running in Cincinnati; Minneapolis NAACP President Rev. Dr. Nekima Levy-Pounds; and many others.

These folks are tasked with the near impossible: rescue decaying communities in a landscape marked by poverty, declining city budgets and city services, under-funded and (re)segregated schools, persistent unemployment and declining availability of affordable housing. Though many policy makers and economic development professionals celebrated the revival of downtowns as the solution to urban crisis, the truth was that poor Black communities lagged behind in the decades of “renewal” marked by the return of the young, affluent and white to the urban core.

Chokwe Antar Lumumba’s remedy for delivering economic justice to his city’s permanent underclass is to turn Jackson, Mississippi, into “the most radical city on the planet.” This is no small feat. How exactly do you create a radical city? What does a radical city look like in the midst of gentrification, food deserts, poor public transportation, climate change and the dogged, intractable 1970s dilemmas of city decline?

Carl B. Stokes and the Cleveland Model

The ascent of these new mayors is an opportunity to build real solutions for those left behind by decades of disinvestment and dispossession. Yet radical intentions and hard-hitting rhetoric is not enough to produce radical answers to economic problems. Black mayors must actively incorporate history and make it an essential part of this project to study the successes and failures of a previous generation. Historian Leonard Moore noted that Cleveland’s Carl Stokes, the first Black mayor of a major urban city, entered politics to wreak havoc on this “corrupt machine,” or rather the political structures that hindered black attainment of power in Cleveland and throughout the United States. However, he quickly learned he “didn’t know where the buttons were.” Not long into his tenure, Stokes not only found the buttons but began pushing them when he launched Cleveland NOW! The project combined private, state, federal, philanthropic and individual funding into a proposed $1.5 billion plan for housing improvement, employment, urban renewal, youth services and economic revitalization.

Cleveland NOW! had community support in the form of neighborhood economic improvement groups, like the Hough Area Development Corporation. But the most sweeping proposal came from an entity created by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), a civil rights organization. During the late 1960s, CORE shifted its focus from desegregation in public accommodation and education toward political community control and municipal development projects. In 1968, CORE created a model for economic development called CORE Enterprises (CORENCO). CORENCO constructed a cooperative wealth-building model that included employee stock ownership, community owned shopping centers and housing developments, and job training designed to promote advancement from manual labor to high tech and industry positions. CORE labored to meld private and public interests in new enterprises that facilitated cooperative ownership and global manufacturing, building links for direct trade with Africa and Asia.

However, both endeavors ultimately failed to permanently transform Cleveland’s circumstances. The reasons are wide and varied, but key factors included a hostile city council, middle-class ambivalence (both Black and white) to low-income housing, media portrayals quick to seek saviors and quicker to assert failures, and short-lived investment from private interests who steadfastly ignored the need for long-term economic commitment.

Current Black mayors and candidates would do well to remember the innovations and processes which produced efforts like CORENCO and Cleveland NOW!, and more importantly, the reasons why they collapsed. They should ask themselves: What barriers did CORENCO/Cleveland NOW! break? How did funding sources become both a political landmine and/or a resource for innovation and experiment? They must courageously question our economic structure and wonder: Is it possible to transform a city through a national network, or must mayors borrow CORE’s idea and establish economic relationships beyond the US borders? How does the political aim of cooperative economy navigate a system still mired in dogmatic adherence to laissez-faire capitalism?

Déjà Vu but Not Quite

Three Black mayors may well be on their way to answering these questions and creating the radical city. The young Michael Tubbs launched his mayoral tenure with a call for universal basic income, a proposal that harkens back to Martin Luther King’s “Other America” contestation that only guaranteed income can end poverty. Chokwe Antar Lumumba intends to find “creative economic development measures [by] looking to structures like cooperative businesses, where the community can decide what it wants to own.” He also has an opportunity to introduce industries that produce jobs for technology and health services, particularly given the recent report on global warming’s effect on economic inequality for the US South.

In Newark, Ras Baraka’s private and public development projects are reshaping the city. The administration just introduced the 2020 plan, which aspires to increase the minimum wage to $15 per hour and expand employment and training programs for city residents. Newark’s new vertical farm (a food cultivation process that made the Netherlands the world’s second-largest food exporter) is particularly exciting and tackles the food desert dilemma. Indeed, there is much to like about this administration and the 2020 plan, but its weakness stems from a dependence on corporate cooperation and solvency. The problems that Black mayors inherited during the 1970s included deserted cities and few hiring opportunities. The 2020 plan gives tax abatements to companies with at least 50 percent hire rate for Newark residents, but the goal for 2,020 workers for 2020 falls quite short of the city’s 29 percent poverty rate — a number that would equal close to 80,000 or more.

Additionally, there is a great need to markedly increase Newark’s promotion of cooperative economics as an alternative that expands community economies that potentially serve as a bulwark against city job losses and an opportunity for Black workers to transition beyond low-wage laborers. The outcome determines whether city development outpaces economic justice, development opens the door to gentrification, and Newark’s future ability to remain financially stable should these corporations desert the city as it did in the 1970s.

While Lumumba, Tubbs and Baraka offer insight for economic development, the potential elections of Farad Ali and Coleman Young, II in Durham and Detroit could point to innovations around housing and the problems of gentrification.

Ali faces a rather challenging space in Durham, North Carolina. Surrounded by its sister cities Chapel Hill, Raleigh, Cary and the Research Triangle Park, investment was slow in the Triangle’s poorer, darker city until population expansion pushed the surrounding areas to its seams. Investors then turned to Durham — pushing out long-time Black businesses and turning Black spaces unrecognizable. As one Durham resident — adjacent to the gentrified American Tobacco District — told me, “We knew they was coming when they put all that new stuff up there and said they would revitalize the neighborhood. But they didn’t. They just bought up everything for nothing, and now look.”

Similar to Harlem, Durham now undergoes a rebranding process where Blackness has proven rather inconvenient. In both places, for instance, conflicts have emerged around the issue of drumming and public space, with longstanding Black cultural traditions provoking hostile reactions from new white residents.

While Durham has investors breathing down its proverbial neck, Detroit wrestles with an even bigger crisis. Mayoral candidate Coleman Young II recalled that his father “beat back stress and the Big Four and diversified the city workforce,” but lamented “What was all that sacrifice for if we’re going to engage in gentrification and Negro removal?” Coleman plans to redirect urban removal funds toward halting home foreclosure, but it is an open question to what extent he can influence state and federal policies.

Young must navigate private interests, state political power and other external groups that operate beyond his control. His father’s experiences and that of other 1970s Black mayors offer insight. Yet regrettably, he insisted in a recent interview that there was no need to evaluate or “question any of the decisions that the Honorable Coleman Alexander Young made.” Proceeding without this reflection, however, is a grave miscalculation. “Opportunity for All,” a report published by The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, has noted that Detroit’s problems are rooted in more than 50 years of housing disparity, education denial, racial segregation and low economic opportunity. Over the long term, Coleman Young’s policies barely alleviated the Black community’s decline, and Detroit’s financial and housing crisis became entrenched. To undo these structural inequalities, Young II and other Black mayors will need to examine how 1970s Black mayors failed to institutionalize processes or a continuum for change over time.

The new Black mayors tread a path well traveled. Though some economic development policies reflect the spirit of the 1970s, there are lost opportunities to institutionalize these ideas beyond the mayor’s tenure and to ensure that uplift equals or outpaces development. From Durham to Detroit, gentrification is the outcome of development without poor and working-class people. This is not to say that the radical city is impossible. The radical city is absolutely crucial for ending urban decline and economic inequality. However, if Black mayors ignore history, they remove one of the most important tools for community transformation. And the city revitalizes while the people are once again left behind.

Nishani Frazier is the author of Harambee City: The Congress of Racial Equality in Cleveland and the Rise of Black Power Populism, an associate professor of history at Miami University of Ohio, and a fellow at The Democracy Collaborative.