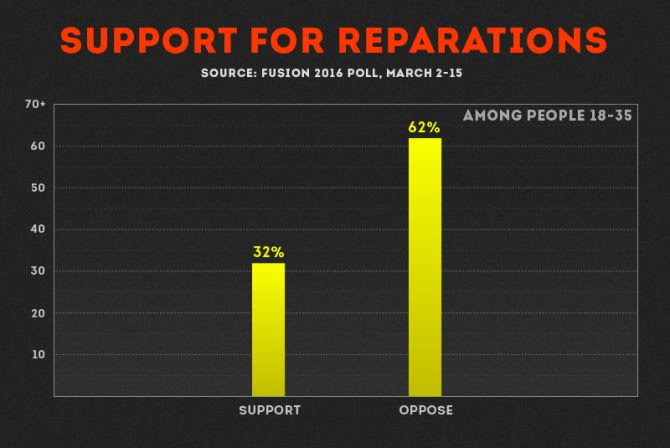

Only half of young Americans between ages 18 and 35 want the U.S. government to formally apologize for slavery, and nearly two-thirds think America should not redress the horrors of slavery by implementing a reparations program through cash payments for black Americans.

These are just two of the findings of the new 2016 Fusion Issues Poll, which surveyed 1,045 adults age 18 to 35 about their views on a number of important social justice issues.

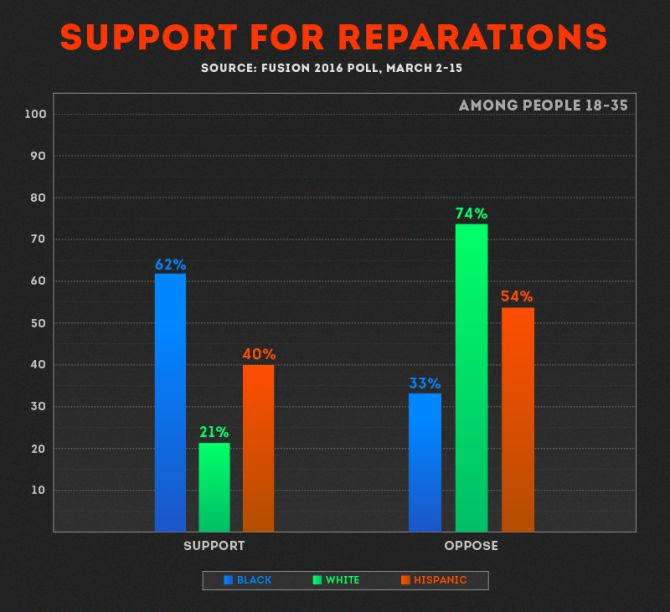

Perhaps predictably, poll respondents split along racial lines on questions of racial injustice. Sixty-eight percent of black respondents and 59% of young Hispanics favored a federal apology to black Americans for slavery, while only 41% of young whites do. Sixty-two percent of young black people favored reparations, while a majority of young Hispanics (54%) and a large majority of young whites (74%) were opposed.

Reparations—the idea that black Americans descended from slaves should receive some sort of financial compensation—has long been a divisive issue, even among progressives. But the debate has taken on new life in recent years, as social movements such as #BlackLivesMatter have brought racial justice to the fore.

None of the candidates from either major party formally supports reparations. (Although Jill Stein, the Green Party candidate, does). Bernie Sanders has called for a federal apology for slavery in this campaign, but when I asked him about reparations at Fusion’s Brown & Black Forum in January, Sanders said he didn’t think reparations were politically feasible:

First of all, its likelihood of getting through Congress is nil. Second of all, I think it would be very divisive. The real issue is when we look at the poverty rate among the African American community, when we look at the high unemployment rate within the African American community, we have a lot of work to do.

Hillary Clinton also dodged the reparations question at the Brown & Black Forum, saying:

I think we should start studying what investments we need to make in communities to help individuals and families and communities move forward. And I am absolutely committed to that.

The progressive case against reparations, as articulated by Adolph Reed, has been that the best way to help black people who have been harmed by the legacy of white supremacy is to build a multiracial movement built on working class solidarity. Conservatives have always argued against race-specific policies.

An apology for slavery, in any form, may seem like a trivial matter. After all, that would do nothing to reverse the injustices we have already committed. But there is evidence that suggests that historical atonement can have an effect on the culture at large, which in turn can have powerful and long-lasting reverberations on the way policy is crafted and carried out.

The leading voice making the case for American reparations has been Ta-Nehisi Coates, arguably the most influential political writer in America today. Coates has argued that after 250 years of slavery, 90 years of Jim Crow, 60 years of so-called “separate but equal” laws, and another 35 years of racist housing policy, the United States has an obligation to redress the systemic and ongoing crimes it has perpetrated on black people if it is ever going to be a nation that is can effectively deal with racism.

Young people may not know that decades after Jim Crow officially ended, the median wealth of white households is still nearly 16 times that of black households. But paying some kind of reparations to black Americans wouldn’t just help address economic inequality—it could also help us avoid repeating the wrongdoings of the past.

Criminal justice lawyer and activist Bryan Stevenson makes this point, traveling to Germany, he was struck by a conversation he had with a German scholar about the death penalty: “There is no way, with our history, we could ever engage in the systematic killing of human beings. It would be unconscionable for us, to in an intentional and deliberate way, set about executing people,” the scholar told him. Stevenson makes the point that in Germany, a nation that paid massive reparations in various ways, the memory of the Holocaust looms large.

“You can’t go anywhere in Germany without seeing reminders of the people’s commitment not to repeat the Holocaust,” Stevenson said. “We don’t do that [in the U.S.]. We do the opposite.”

Indeed. In fact, while the U.S. still has hundreds of Confederate memorials all across the South, we have only one federal slavery memorial (it’s in Philadelphia, and it’s falling apart). Reckoning with America’s history of white supremacy, whether through a formal apology for slavery or financial reparations for black Americans, would help keep the horrors of the past fresh in our national memory.

In an interview with Democracy Now, Coates said that if he could have one thing from a presidential candidate, it would be a “greater acknowledgement of history.” Our polling, however, shows that many young Americans do not want a greater acknowledgement of our slave-owning past.