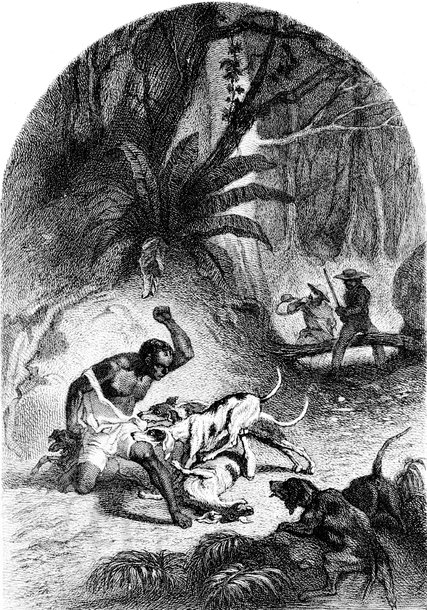

The capture of a black slave attempting to run away from a plantation. Engraving, around 1860. Credit Apic/Getty Images

NEW HAVEN — LAST week, a milestone passed for my family in South Carolina — the 150th anniversary of the last day of slavery. We were the slaveholders.

At the start of March 1865, a company of black Union soldiers from the 35th United States Colored Troops regiment rode up the oak allée of Limerick, one my family’s rice plantations north of Charleston, where 250 of our slaves lived and worked. At the head of the column was a white colonel named James Beecher, a brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

It was a Sunday, and the family of William Ball, my great-great-grandfather, sat in the dining room, reading from the book of Lamentations. With the Civil War rushing to its end, they must have found it an apt choice: The passage recounted the miserable fate of Jerusalem condemned by God for its sins: “She that was great among the nations, and princess among the provinces … she weepeth sore in the night … for the Lord hath afflicted her for the multitude of her transgressions.”

That morning, the Ball women had put on two dresses, afraid that they might be raped, as the papers had told them to expect from black Yankees, just like the ones now approaching the house.

Behind the big house at Limerick, on the slave street, the mood was high and restless. Everyone knew the hour had finally arrived. Turning from the lawn of the mansion, the black company headed soundlessly to the barn, where soldiers pulled down the bell that had been used to call field hands to work, six dawns a week for a century, and smashed it to pieces.

William Ball opened his front door to admit Colonel Beecher. The white officer and abolitionist had one demand: “I want to see all the people on this place, now, in front of the house.” The black village gathered — field hands, cooks, boatmen, hostlers, nurses, carpenters, mothers, seamstresses, children, old people — and Beecher yelled, “You are free as birds, you don’t have to work for these people anymore!”

Many in the black village, according to a diary, danced and sang, while others fell to their knees and prayed. That night the scene gradually turned to one of drunkenness and music. The food stores were emptied, the china was smashed and a tent city went up on the lawn for the invaders — or liberators.

Early 1865 was the season when millions were freed from slavery, as Yankee armies crisscrossed the Deep South and unlocked the gates of a thousand plantations. I imagine these scenes were similar to ones at the end of World War II in Europe, when American and Soviet armies arrived at the gates of the German camps in Central and Eastern Europe. In popular memory — in white memory — the plantations of the antebellum South were like a necklace of country clubs strewn across the land. In reality, they were a chain of work camps in which four million were imprisoned. Their inhabitants, slaves, were very much survivors, in the Holocaust sense of that word.

Colonel James Chaplin Beecher, circa 1863.

That was a long time ago, and everything has changed, people say. But the poet Claudia Rankine describes memory like this, in her book “Citizen,” published last fall: “The world is wrong. You can’t put the past behind you. It’s buried in you; it’s turned your flesh into its own cupboard. Not everything remembered is useful, but it all comes from the world to be stored in you.” If by some method of time travel the former slaves and slaveholders of Limerick plantation could be brought face to face with us, they would not find our world entirely alien. In place of the rural incarceration of four million black people, we have the mass incarceration of one million black men. In place of laws that prohibited black literacy throughout the South, we have campaigns by Tea Party and anti-tax fanatics to defund public schools within certain ZIP codes. And we have stop-and-search policing, and frequently much worse, in place of the slave patrols.

The first armed police force formed in the South was assembled to apprehend black people. These “slave patrols” rode down country lanes and seized people, invariably young black men, who did not have proper papers to be away from their home plantation. They were regarded as suspect, by reason of their color and situation. My ancestor William Ball often rode in a slave patrol, as did other male members of my family, as well as every other slaveholding clan. Deadly force was often used against slaves who resisted being taken into custody. When a “suspicious” slave was arrested, he was sent to a jail in Charleston called the Work House, to labor for the city, increasing its revenue and keeping the government budget in balance.

Earlier this month the Justice Department found the police in Ferguson, Mo., culpable for conducting a continual dragnet in which they stopped, harassed and took into custody black citizens in disproportionate numbers. African-Americans make up approximately 90 percent of traffic stops and tickets, and nearly 95 percent of arrests, in Ferguson. Furthermore, according to Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr., the courts of the largely black and yet white-run town use arrests and fines against African-Americans to raise revenue and keep the city budget from falling into deficit. It’s hard to imagine that Ferguson is alone among American cities in applying this strategy.

I do not mean to suggest that police forces of today are like slave patrols. I do not mean to imply that the long roster of deaths of unarmed black men at the hands of the police — from Eric Garner, in July, on Staten Island; to Michael Brown, in August, in Ferguson; to Ezell Ford, in August in Los Angeles; to 12-year-old Tamir Rice, in November, in Cleveland; to Akai Gurley, in November, in Brooklyn; to Rumain Brisbon, in December, in Phoenix; to Tony Robinson, last week, in Madison, Wis. — is a result of police behavior that resembles that of antebellum slave patrols, which routinely killed young black men, and faced no punishment for doing so.

No, that would be overstatement. Yet lying behind such recent events is a mentality that originates during the slave period, and provides police action with an unconscious foundation. A mentality that might be called part of the legacy of slavery. “The past is buried in you,” as Ms. Rankine says.

Edward Ball is the author of “Slaves in the Family” and, most recently, “The Inventor and the Tycoon.”