By Shawn Fremstad

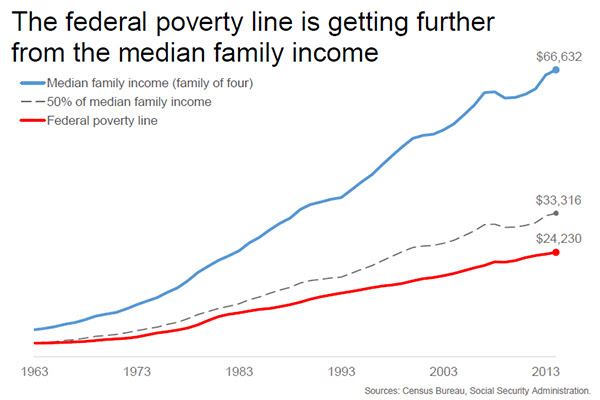

In 1963, the poverty line for a family of four was 50% below median family income—or one-half of the income of the typical four-person family in America. Today, however, the poverty line for a family of four is nearly 75% below median family income. (Photo: AP/Craig Ruttle)

The U.S. Census Bureau’s announcement today that the number of Americans living below the poverty line fell between 2014 and 2015 is good news. But before we get too excited, it is worth noting that the federal poverty line was a meager $12,000 for a single person living alone in 2015 (and only about $24,000 for a married couple living with two children).

If your initial reaction to that is “whoa, that’s waaay too low for a person to lead a minimally decent life on in the USA,” then you’re in good company. In a recent survey conducted by the conservative American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and the Los Angeles Times, Americans were asked, “[What is the] highest annual income a family of four can have and still be considered poor by the federal government.” The average response was $32,293—an amount 34 percent higher than the current federal poverty measure.

In short, conservatives did a poll on how much income it takes to avoid poverty, and the answer they got back was more than $8,000 above the federal poverty line.

The wonks reading this might be thinking “well, if the federal government says a married couple with their two kids only needs $24,000 to live a minimally decent life, then they must have good reasons to think this is enough.” I’m a bit wonkish myself and generally trust official government statistics—but the federal poverty measure is a big exception.

The main reason I don’t trust this approach to measuring poverty is shown in the figure below. In 1963, the poverty line for a family of four was 50% below median family income—or one-half of the income of the typical four-person family in America. Today, however, the poverty line for a family of four is nearly 75% below median family income.

That means to be officially counted as poor today, a family has to be much poorer compared to the typical American family than it had to be in 1963. In fact, if the federal poverty line today was set at the same place relative to median income as it was in 1963 it would be about $33,000, rather than $24,000.

The AEI survey results are not a fluke. We know from decades of evidence that the public’s understanding of the income needed to avoid poverty increases over time at a rate faster than inflation, and closer to the increases in mainstream incomes and living standards.

So why hasn’t the official poverty line been adjusted over time in a way that reflects the public’s more accurate understanding?

The reasons for this are largely political.

In the early 1960s—around the time when the Beatles were just becoming famous here—Mollie Orshansky, an employee in the Social Security Administration (SSA), developed working estimates of what it meant to be poor at that time.

The data available to Orshansky wasn’t particularly sophisticated, or even timely. For example, she based her estimates in part on a food consumption survey conducted in 1955. When the federal government started using her calculation of the poverty line in the mid-1960s, Orshansky and federal officials understood that it would need to be adjusted over the long-term for increases in mainstream living standards. The SSA “made a tentative decision early in 1968 to adjust the poverty thresholds for the higher general standard of living.”

But then two things happened that year. First, officials in the Johnson administration prohibited the SSA from making this kind of adjustment, likely in part due to concern that the updated figures would show an increase in poverty. Second, Richard Nixon was elected President. After he took office, his budget office issued a directive making the Orshansky thresholds the “official” poverty measure, and specifying that they would be adjusted for inflation only.

There have been repeated recommendations to reform the poverty measure

In 1970, Orshansky said this decision would likely “freeze the poverty line despite changes in buying habits and changes in acceptable living standards.” There have been repeated recommendations to reform the poverty measure since then, but no President has been willing to revise the Nixon directive.

The Census Bureau has an alternative measure of poverty, the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which improves the current federal poverty measure in many respects. But even this approach puts the poverty line at about $25,000 to $26,000 for a family of four—and that’s still too low.

Here’s a better approach: dump the current official poverty measure and replace it with two different measures. One measure would be anchored to half of the typical (median) American family’s income in 2016 and then adjusted for inflation over time; the other would be set at the same level initially, but adjusted annually using the median income over a 5-year period. This way, the poverty line won’t drift away from mainstream living standards of living over time.

It’s 2016: We need a poverty measure that reflects what the public thinks is required to meet basic needs in Beyoncé America. But instead we’re stuck in Beatlemania America—and that needs to change.

|

12:51 PM (1 hour ago)  |

|

||

|

||||

Black Lives Matter Fighting Alongside Dakota Access Pipeline Protesters

By Ashoka Jegroo

There’s been growing solidarity between the #BlackLivesMatter and #NoDAPL movements in recent weeks, and activists in New York are looking to strengthen that bond even more.

On Aug. 27, Black Lives Matter activists from Minneapolis and Torontotr

“We decided that we really need to stand in solidarity with the tribes out in Standing Rock because we know very well that all of our struggles are connected, and until we unite, we’re never going to win,” Kim Ortiz, organizer of NYC Shut It Down, told me.

NYC Shut It Down is one of several grassroots, anti-police brutality groups from New York City that will be in Standing Rock from Sept. 14 to 18. Its goal? To deliver supplies, and support a coalition of hundreds of tribes that want to stop the DAPL’s construction. Other groups traveling there include Millions March NYC, Copwatch Patrol Unit, and Equality for Flatbush, all of which are active in the city’s Black Lives Matter movement.

On Friday, these groups also helped New York City-based #NoDAPLactivists organize and promote a rally in Washington Square Park. Earlier that day, a judge denied the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s request to halt construction on the pipeline. But then, minutes later, three federal agencies issued a statement requesting that Texas-based pipeline developer Energy Transfer Partners “voluntarily pause” construction within 20 miles east or west of Lake Oahe—land the tribe considers sacred.

Despite the Obama administration’s support, however, Friday evening’s rally went on as planned because activists “do not see [the statement] as having any teeth,” Rally for Standing Rock organizer Audra Simpson said.

And so, hundreds gathered in Washington Square Park for several hours of speeches, songs, drum-beating, and chants of “water is life.” Organizers also collected piles of donated items—including school supplies, tents, blankets, sleeping bags, medical supplies, and coats—a portion of which will be delivered to Standing Rock by the BLM contingent.

For the activists, this kind of support between black and indigenous movements is the only way they’ll be able to defeat their common oppressors.

“It’s a pronouncement of solidarity, empathy, and support for each other in our intersecting movements and attempts to stay alive in a settler state that has targeted us differently for life and for death,” Simpson, a Columbia University professor of Mohawk descent, said.

Red Sky Harjo, a 22-year-old student, communicates regularly with his father and three cousins who are currently protesting in Standing Rock. Harjo said he was happy to witness unity among the various indigenous tribes protesting the DAPL, as well as BLM’s support for their cause.

“We have all these nations coming together, which I don’t think anybody ever thought was possible. And with Black Lives Matter, it’s just an added plus for the two movements to stand in solidarity with one another,” Harjo told me at Friday’s rally.

“I’ve been down with the Black Lives Matter movement since the beginning because white America just doesn’t understand the residual effects that going through slavery and going through a genocide has on future generations.”

Abby Rojas, a 22-year-old Mexican American of Tlaxcaltec descent and member of NYC Shut It Down, organized BLM’s upcoming trip to Standing Rock. Rojas said she was first inspired to join the #NoDAPL movement after meeting Victor Puertas, an activist with the anti-DAPL collective Red Warrior Camp, who told her about the situation. Then she and Ortiz found out about Defenders of the Water School, a makeshift Native school at Standing Rock, on Twitter. They decided to help by donating school supplies, but soon expanded the purpose of their trip.

“It all began when the donations began for the new school that’s coming up in Standing Rock, and everyone in NYC Shut It Down was willing to help. So we just decided to go as a group to help out the school,” Rojas told me. “But it became a bigger thing. Now, we’re just looking for supplies for the whole camp.”

In addition to the supplies collected at Friday’s rally, NYC Shut It Down set up a GoFundMe page on Aug. 31 to collect donations for protesters at Standing Rock, and ultimately raised $4,782. The activists are using this money to buy school supplies and fund their trip to North Dakota.

Imani Henry, a community organizer with Equality for Flatbush, is one of several New York-based BLM activists who traveled to Standing Rock earlier than the rest of his colleagues. “I am in solidarity to bear witness to this struggle, lend a hand in the kitchen, bring supplies, and do whatever is asked,” Henry, who flew to North Dakota on Sept. 9, told me via Facebook Messenger.

Beyond donating supplies and showing solidarity, one group called Copwatch Patrol Unit plans to act as a watchdog against police and private security forces, which reportedly behaved aggressively towards #NoDAPL protesters earlier this month.

“We are going to stand in solidarity with the Standing Rock Reservation after media reports of road blockades, security attacking people with dogs, and rumors of law enforcement overstepping their boundaries,” Michael Barber, a member of Copwatch Patrol Unit, told me at Friday’s rally. “So I’m going there to live-stream and document the police state that we all live in right now. Basically, the revolution will be televised.”

Much like the indigenous tribes they’re supporting, Black Lives Matter activists from New York City see themselves engaged in a fight against state violence, oppression, and exploitation. For these activists, black and indigenous struggles are intimately tied together.

“I think we’re starting to see that a lot of these movements are related, that there’s intersectionality between issues of social justice and issues of environmental racism,” Tara Houska, national campaigns director of the indigenous environmental-justice group Honor The Earth, told me. “We know that our communities are not only targeted by police and killed at a disparate rate by police officers, we also know that our communities are targeted at a disparate rate by these projects.”

Solidarity between Black Lives Matter and indigenous tribes are part of a long tradition of black and Native unity in the face of injustice, activists say.

“Solidarity and kinship between African peoples and the peoples of the Americas is almost 500 years old,” Equality for Flatbush’s Henry said. “We proudly have fought together in wars against European invaders and slavery, from Jamaica to Florida and elsewhere. This is why thousands of people of color claim both black and indigenous nations as their racial and cultural identities.”

And since black and indigenous people have historically been victimized by the state, activists on both sides see these movements as urgent battles for survival.

“We’re talking about forced enslavement, dispossession, corporate privatization of natural resource, and we see this from the Bronx to Flint to Standing Rock. And the key point is that this entire system is made possible by the police institution, by the prison system, which functions as the enforcement arm of this violent system,” Vienna Rye, an organizer with Millions March NYC, told me over the phone.

“Standing Rock is really the epitome of why reform continues to kill us, and why we need abolition. These institutions have proven, time and time again, that they can’t be reformed. Standing Rock is evidence 400 years later.”

Ultimately, though, both movements are cooperating because they know they’re much stronger together than apart.

“Native Americans have been through so much. African Americans have been through so much,” NYC Shut It Down’s Ortiz said. “And we will never be free until we unite and get free.”