“I think we should—we should advocate for the end of the embargo” on Cuba, Hillary Clinton said in an interview this summer at the Council on Foreign Relations. “My husband tried,” she declared, “and remember, there were [behind-the-scenes] talks going on.” The way the pre-candidate for president recounts this history, Fidel Castro sabotaged that process because “the embargo is Castro’s best friend,” providing him “with an excuse for everything.” Her husband’s efforts, she said, were answered with the February 1996 shoot-down of two U.S. civilian planes by the Cuban air force, “ensuring there would be a reaction in the Congress that would make it very difficult for any president to lift the embargo alone.”

The history of this dramatic episode is far more complicated than Hillary Clinton portrays it. But she is correct about one thing: Should she become president, it will be far harder for her to lift the 50-year-old trade embargo against Cuba than it would have been when her husband first assumed the office. The person most responsible for that, however, is Bill Clinton.

* * *

The beginning of Bill Clinton’s presidency marked a change in tone on Cuba policy. Personally, Clinton understood the folly of a hostile U.S. posture toward the island. “Anybody with half a brain could see the embargo was counterproductive,” he later told a confidante in the Oval Office. “It defied wiser policies of engagement that we had pursued with some Communist countries even at the height of the Cold War.”

The Clinton administration’s early initiatives included public assurances that the United States posed no military threat to Cuba—to reinforce the point, U.S. officials began alerting Cuban authorities in advance of routine naval maneuvers near the island and opened low-level discussions on cooperation against narcotics trafficking. U.S. officials also dialed back the anti-Castro rhetoric. In Havana, the Cubans recognized and appreciated the change in tone. “There is less verbal aggression this year in the White House than in the last 12 years,” Raúl Castro told a Mexican reporter. Still, the administration worked overtime to assure the exile community and congressional Republicans that no opening to Cuba would be forthcoming. U.S. policy, stated Richard Nuccio, the Clinton administration’s special advisor on Cuba, was to “maintain the existing embargo, the most comprehensive we have toward any country.”

“Anybody with half a brain could see the embargo was counterproductive.”Hard-liners in Congress were not reassured. Senate majority leader and Republican presidential hopeful Robert Dole declared that “all signs point to normalization and secret negotiations with Castro.” In September 1995, the House passed legislation co-sponsored by Senator Jesse Helms and Representative Dan Burton that prohibited U.S. assistance to Cuba until the advent of democracy and imposed sanctions against foreign countries and corporations that did business on the island. “It is time to tighten the screws,” Senator Helms announced when he first presented the bill to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Congressman Burton predicted that passage would be “the last nail in [Castro’s] coffin.”

Helms-Burton became a bitter battleground between the executive and the legislative branches. Not only did the bill “attack the President’s constitutional authority to conduct foreign policy,” according to a White House legislative-strategy memorandum for Clinton, “Helms-Burton actually damages the prospects of a democratic transition in Cuba, and could conflict with broader U.S. interests, including compliance with major international trade agreements … and our commitment to respect international law.” Secretary of State Warren Christopher threatened a presidential veto.

* * *

As the Helms-Burton legislation dominated public debate on Cuba policy in the latter half of 1995, a veritable Greek tragedy played out in the skies over Cuba’s coast—a tragedy set in motion by repeated incursions into Cuban airspace by a group of Cuban-American pilots known as Brothers to the Rescue (BTTR). Since 1991, the Brothers had been flying search missions for distressed Cuban rafters who had begun to flee Cuba for the U.S. by the hundreds, and then by the thousands, notifying the U.S. Coast Guard whenever a small boat or raft needed rescue.

But despite its humanitarian mission, BTTR’s founder and director, José Basulto, had a history of anti-Castro violence. In April 1961, Basulto had, along with some 1,500 Cuban exiles trained by the CIA, participated in the failed Bay of Pigs invasion aimed at overthrowing Castro. In August 1962, he had positioned a boat with a 20mm cannon on its bow just off the coast of Havana and shelled the Hornedo de Rosita hotel, where he and his co-conspirators believed Castro would be dining. “I was trained as a terrorist by the United States, in the use of violence to attain goals,” Basulto said in an interview with a documentary filmmaker, but he claimed to have converted to nonviolence. “When I was young, my Hollywood hero was John Wayne. Now I’m like Luke Skywalker. I believe the force is with us.”

After secret back-channel diplomacy ended the rafters crisis in the fall of 1994, Basulto shifted BTTR’s mission from rescue to provocation. On November 10, Basulto dropped Brothers to the Rescue bumper stickers over the Cuban countryside. Repeatedly over the next eight months, BTTR planes violated Cuban airspace. Their most provocative act in 1995 came on July 13, when Basulto’s Cessna Skymaster buzzed Havana, raining down thousands of religious medallions and leaflets reading “Brothers, Not Comrades” along the Malecón, Havana’s broad seaside avenue. “We are proud of what we did,” Basulto exalted on local TV after landing back in Miami. “We want confrontation,” Basulto declared, boasting that his bold incursion served “as a message to the Cuban people. … The regime is not invulnerable.”

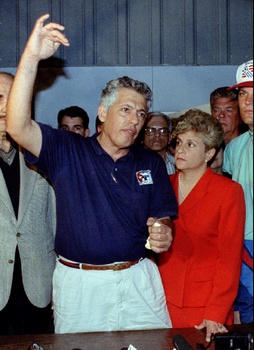

José Basulto, founder of Brothers to the Rescue,

José Basulto, founder of Brothers to the Rescue,

in 1996 (Colin Braley/Reuters)The overflights constituted a direct challenge to Cuba’s national security and a flagrant affront to its sovereignty. “It was so humiliating,” Castro later told Time magazine. “The U.S. would not have tolerated it if Washington’s airspace had been violated by small airplanes.” Castro and his generals had long memories of the early years of the revolution when little planes would take off from Florida and drop incendiary devices over the Cuban countryside as part of the CIA’s covert war of sabotage.

Given that dark history, Cuban officials made it clear to the Clinton administration that the incursions could not and would not be tolerated. The Cubans filed one diplomatic protest after another, warning in a note after the July 13 incursion that Cuban security forces had a “firm determination to adopt whatever positions are necessary to avoid acts of provocation,” and “any boat from abroad can be sunk and any airplane downed.” In Miami, U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) officials met face-to-face with Basulto to warn him to stay away from Cuba. State Department officials meanwhile used diplomatic notes to request that the Cuban government exercise “the utmost discretion and restraint and avoid the use of excessive force” in dealing with the incursions.

But BTTR and Basulto continued their provocations. Between August 1995 and February 1996, the Cuban government filed four more diplomatic notes protesting violations of its airspace—only to have the FAA request additional evidence, since the agency had determined Basulto could not be grounded until it had fully completed an enforcement investigative report. Emboldened by his seeming impunity, on January 13, 1996, Basulto again flew his planes over Havana, this time dropping a half a million leaflets exhorting the Cuban people to “Change Things Now.” His ability to penetrate Cuban airspace, Basulto bragged on the radio back in Miami, demonstrated that “Castro isn’t impenetrable, that many things are within our reach to be done.”

The Cuban military tried to send a warning through private channels. At one point Cuban Air Force Brigadier General Arnaldo Tamayo Méndez briefed a visiting delegation of retired U.S. officers on the BTTR overflights, warning that Cuba had the capability “to bring them down at any moment.” Tamayo explained: “We haven’t done so precisely because we do not want to overheat the situation, because then, of course, Cuba will be presented as a culprit, and the violators and those who stimulate these acts of piracy against us will get off scot free.” Castro, he told two of the delegates in a side conversation, had given a standing order to the air force to take all necessary steps to prevent another violation of Cuban airspace. “Are you going to wait until they drop a bomb on me before you take action?” Castro had asked his commanders in frustration.

“What would be the reaction of your military if we shot down one of those planes?” Tamayo asked the visiting Americans, who were stunned by the question.

* * *

The highest-level effort at secret diplomacy was undertaken by Fidel Castro himself. The Cuban leader seized the opportunity of a January 1996 visit by Bill Richardson to propose an unusual quid pro quo: political prisoners in exchange for grounding Basulto. Then a relatively unknown congressman from New Mexico with close ties to President Clinton, Richardson had developed a reputation for humanitarian missions abroad, having previously succeeded in talking Saddam Hussein into turning over two Americans Iraq had been holding on suspicion of espionage.

On arriving in Cuba, Richardson found Castro to be a “personable guy, engaging and humorous,” as he wrote in his memoir. Fidel gave Richardson the red-carpet treatment, taking him to a baseball game, holding a lengthy nighttime meeting to discuss U.S.-Cuban relations, and giving him a box of premium Cuban cigars as a gift for President Clinton. (They were confiscated by the Secret Service before the president ever knew about the gift.) He also, according to Castro biographer and former Carter White House official Peter Bourne, told Richardson he would release some political prisoners if the congressman could secure Clinton’s assurance that the Brothers to the Rescue flights would be stopped.

“What would be the reaction of your military if we shot down those planes?”Richardson returned to Washington and purportedly raised the issue with the president, who instructed Secretary of Transportation Federico Peña to put an end to the flights. When Richardson came back to Havana on February 9 to ferry three prisoners back to the United States, Castro felt he came with a promise that Clinton would halt the violations of Cuban airspace. Castro, according to Bourne, had told Richardson he was releasing the prisoners in the belief that “he had a clear commitment from one head of state to another that the flights would be stopped.”

But as he returned to Florida with the released prisoners, Richardson told CNN reporters that Castro had asked for nothing in exchange; he denied the existence of a quid pro quo to a New Yorker reporter two years later. Revisiting this episode in 2011, however, Richardson acknowledged that he had, in fact, approached the White House about the BTTR flights, although he could not recall to whom he had spoken.

Years later, after stepping down from power, Castro recalled that Richardson had “very earnestly told me, to the best of my recollection, the following: ‘That will not happen again; the president has ordered those flights stopped.'” When BTTR once again violated Cuban airspace only two weeks later, Bourne reported, “Castro was outraged and fuming over Clinton’s behavior which, he felt, showed his word meant nothing.”

* * *

In the weeks, days, and hours before the final confrontation in the skies off Cuba’s coast, some U.S. officials sensed a calamity was coming. In January, U.S. military radar picked up evidence that the Cuban air force was practicing intercepting and firing on slow-moving aircraft. Alarmed State Department officials peppered the FAA with requests for action. “State is increasingly concerned about Cuban reactions to these flagrant violations,” wrote Cecilia Capestany, an official at the FAA’s international-aviation division, on January 22, 1996. “Worst-case scenario is that one of these days the Cubans will shoot down one of these planes …”

Cecilia Capestany’s email of January 22, 1996 (National Security Archive)At the White House on the evening of February 23, Richard Nuccio received an alert that BTTR would be flying the next day. He fired off an urgent email to Deputy National Security Advisor Sandy Berger. “Previous overflights by José Basulto of the Brothers have been met with restraint by Cuban authorities. Tensions are sufficiently high within Cuba, however, that we fear this may finally tip the Cubans toward an attempt to shoot down or force down the plane,” Nuccio warned.

Cecilia Capestany’s email of January 22, 1996 (National Security Archive)At the White House on the evening of February 23, Richard Nuccio received an alert that BTTR would be flying the next day. He fired off an urgent email to Deputy National Security Advisor Sandy Berger. “Previous overflights by José Basulto of the Brothers have been met with restraint by Cuban authorities. Tensions are sufficiently high within Cuba, however, that we fear this may finally tip the Cubans toward an attempt to shoot down or force down the plane,” Nuccio warned.

Nuccio instructed FAA officials in Miami to halt the flight, but to his surprise, they refused; they would agree only to “warn Basulto again about violating Cuban airspace.” The best Nuccio could do was try to alert the Cuban government. Told that an approach through semi-official channels “may actually make things worse,” Nuccio grasped at his one remaining opportunity to alert the Cubans: the ballet.

By coincidence, that very evening Nuccio was scheduled to attend the performance of Cuba’s Ballet Folklórico—a major cultural event made possible by a people-to-people initiative Clinton had initiated. Aware that Fernando Remírez, the new chief of Cuba’s de facto diplomatic arm in Washington, the Cuban Interest Section, would also be attending, Nuccio hoped to meet him there, casually, for the first time, since he was not allowed to meet formally with Cuban diplomats. But an informal, accidental introduction could be useful in a future crisis. “I really just wanted to open a dialogue with Remírez,” Nuccio told the authors. “I visualized someday having to be on the phone saying harsh things to this guy and I wanted him to know something about me.”

As the troupe danced its way through the rich history of Cuban music, Nuccio was in a “state of anxiety” over the BTTR flights. But when the chance came to meet Remírez at the post-performance reception, the two engaged in only perfunctory small talk. The most substantive exchange came as Remírez commented on the difficult state of U.S.-Cuban relations. Nuccio’s Mexican-born wife, Angelina, then reminded him of a famous saying in her country: “So far from God, so close to the United States.”

“Yes, that’s it,” Remírez replied. “You understand us exactly.”

As the pleasantries concluded, Nuccio faced a critical decision: whether to warn the Cuban official about the impending incursion. “I recall looking at Remírez as he moved toward the door and fighting with my impulse to pull him aside,” Nuccio later wrote in an unpublished memoir. “I struggled with a gut instinct to appeal to the Cubans to exercise restraint in reacting to the flight and the worry that my remark would be misinterpreted if something tragic did occur.” The security of silence prevailed. “As Remírez exited, I turned back to the bar and said nothing.”

* * *

At 1:15 p.m. the next day, Basulto’s plane took off from Opa-Locka airport in Miami, accompanied by two other BTTR Cessnas. They filed a false flight plan with the FAA to patrol off the northern coast of Cuba in search of rafters. In reality, their mission was to again penetrate Cuban airspace as an act of solidarity with a Cuban dissident group called Concilio Cubano. In a crackdown on opponents, Castro’s police had arrested dozens of Concilio members a few days before.

“Good afternoon, Havana Center,” Basulto radioed Cuban flight controllers as the planes headed toward the island. “A cordial greeting from Brothers to the Rescue and its President José Basulto.”

The Cuban controllers immediately warned him not to cross into their airspace. “I inform you that the zone north of Havana is active. You run danger by penetrating that side of North 24.”

“We are ready to do it,” Basulto responded with bravado. “It is our right as free Cubans.”

Acting on Castro’s standing orders to prevent another penetration of Cuban airspace, two MiG-29 jets scrambled from their base at San Antonio de los Baños. The Cuban pilots followed none of the international protocols for warning, intercepting, and escorting unarmed civilian planes. Instead, at 3:19 p.m., a heat-seeking missile obliterated the first BTTR Cessna; at 3:26, the second was shot down. The attack took the lives of four young Cuban-Americans: Mario de la Peña, Armando Alejandre, Carlos Costa, and Pablo Morales. Only Basulto and his three crew members escaped back to Miami.

Cuban exiles scream “Death to Castro” following the shoot-down of Brothers to the Rescue planes in February 1996. (Reuters)In Washington, the shoot-down generated a full-scale crisis. Within minutes, Nuccio received a call to report immediately to Sandy Berger’s office; there he was tasked to draw up “tough” options, including “military responses,” for President Clinton’s consideration. Nuccio cautioned against an overreaction. BTTR had “been playing with fire,” he told Berger. “They got exactly what they were hoping to produce. If we respond militarily, they will have succeeded in producing the crisis they’ve been looking for.” But the blatantly provocative nature of the BTTR flights no longer mattered. The United States, Berger told him, could simply not “stand by and let Castro kill American citizens.”

Cuban exiles scream “Death to Castro” following the shoot-down of Brothers to the Rescue planes in February 1996. (Reuters)In Washington, the shoot-down generated a full-scale crisis. Within minutes, Nuccio received a call to report immediately to Sandy Berger’s office; there he was tasked to draw up “tough” options, including “military responses,” for President Clinton’s consideration. Nuccio cautioned against an overreaction. BTTR had “been playing with fire,” he told Berger. “They got exactly what they were hoping to produce. If we respond militarily, they will have succeeded in producing the crisis they’ve been looking for.” But the blatantly provocative nature of the BTTR flights no longer mattered. The United States, Berger told him, could simply not “stand by and let Castro kill American citizens.”

When President Clinton convened his top national-security team two days later, he considered a surgical airstrike or cruise-missile attack on Cuba’s MiG base but decided against it. Instead Clinton ordered that a private warning be sent to Castro: “The next such action would meet a military response directly from the United States.” In addition, Clinton ordered a new ban on commercial flights between Cuba and the United States, restricted Cuban diplomats from traveling outside of their posts in New York and Washington, and authorized compensation for the families of the four BTTR victims from frozen Cuban bank accounts.

More importantly, the president declared that he would “move promptly” to reach an agreement with Congress to pass the Helms-Burton legislation. Emboldened and empowered, anti-Castro forces in the Congress added a dramatic new clause to the bill—the codification of the embargo into law. No longer would it be a presidential prerogative to lift sanctions against Cuba; now it would take majority votes in Congress. The Clinton team put up no objections.

Nuccio tried to argue against this wholesale capitulation on Helms-Burton, only to be overruled. “Forget it,” Undersecretary of State Peter Tarnoff told him. “The decision’s been made. It’s over.” That verdict was about more than just Helms-Burton, Nuccio knew. “He was saying that our gambit to improve relations was over, done.” Shortly thereafter, Nuccio stepped down as White House special advisor on Cuba.

On March 12, 1996, with the families of the four BTTR pilots standing behind him, President Clinton signed the Helms-Burton bill into law as a “powerful, unified message to Havana.” Clinton understood what he had done. He felt “backed into a policy of proven failure,” he lamented to a confidante in the Oval Office, “closing off political engagement toward a peaceful transition in Cuba” for the sake of electoral expediency. “Supporting the bill was good election-year politics in Florida,” Clinton conceded in his autobiography, “but it undermined whatever chance I might have had if I won a second term to lift the embargo in return for positive changes within Cuba.”

With that political calculus, Clinton gave up his presidential authority to make policy toward Cuba, and the authority of the presidents who would succeed him. That includes his wife, should she win the presidency in 2016.

This article has been adapted from Peter Kornbluh and William M. LeoGrande’s new book Back Channel to Cuba.