By Manisha Sinha

The nation was a beacon for the anti-slavery cause

UNESCO has chosen Aug. 23 to commemorate the International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and Its Abolition, but the historical significance of that day may escape many. On the night that spanned August 22 and 23, 1791, slave rebels in the French colony of Saint-Domingue started the Haitian Revolution, the only instance of a successful slave rebellion in world history and the founding event of the first modern black republic. More than the American Revolution and its aftermath, which resulted in the gradual abolition of slavery in the northern states, the Haitian Revolution, which continued until 1804, constitutes a landmark in the history of abolition. It highlighted the abuses of slavery and dealt a blow to the Atlantic Slave Trade, the profitable and inhumane traffic in human beings from the west coast of Africa to European colonies and countries in the Americas.

The history of abolition begins with those who resisted slavery at its inception. African resistance to enslavement—epitomized in the more than 200 shipboard insurrections that dot the four centuries of the slave trade and in maroon communities of runaway slaves on both sides of the Atlantic—is often forgotten in the recent scholarship on African nations’ participation in the slave trade.

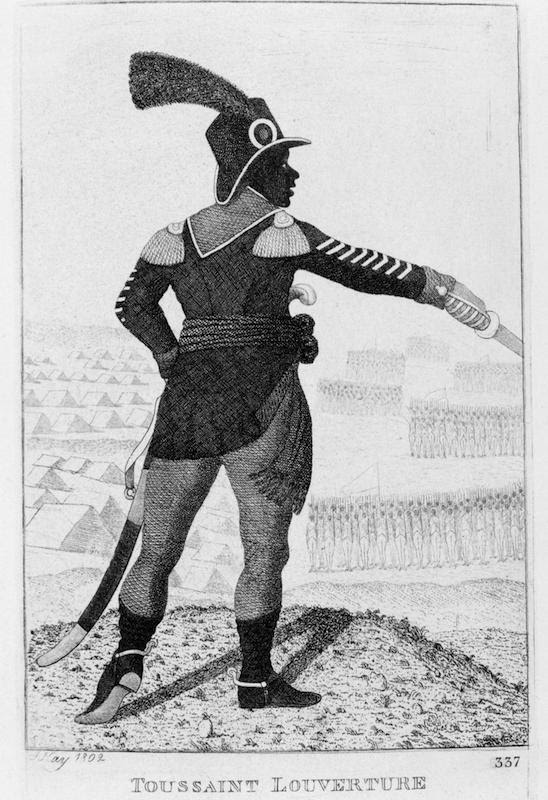

The “Black Jacobins” of Haiti were not only influenced by the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of the French Revolution of 1789, but also by the long tradition of petit marronage and slave resistance established by enslaved Africans in Saint-Domingue. Under the brilliant military leadership of Toussaint Louverture—who warded off challenges to his authority by slaveholders, free men of color, French emissaries and the armies of the slaveholding British and Spanish empires—black Saint-Dominguans laid the foundation for Haitian independence after 13 years of unremitting warfare. Louverture was eventually imprisoned and died in France, but his successors defeated the world-conquering army of Napoleon, who, after the first French Republic attempted to abolish slavery, re-established the practice in the rest of the French empire.

More than 300 years after Christopher Columbus landed in Hispaniola, destroyed its native population and introduced African slavery, the island witnessed the birth of the independent Republic of Haiti, its native name, on Jan. 1, 1804. The Haitian Declaration of Independence simply stated, “We have dared to be free, let us be thus by ourselves and for ourselves.”

Four years later, on that very date, Britain and the United States abolished the African slave trade. Interestingly enough, the first instances of modern racial slavery did not take place from Africa to the Americas but among the native Taino population of Hispaniola, who virtually disappeared through warfare, disease and enslavement by the Spanish. In the long history of the slave trade and European colonization of the Americas, the Haitian revolutionaries were truly “Avengers of the New World.”

Their bloody, decisive challenge to slavery and white supremacy—notwithstanding Haiti’s subsequent political instability and poverty, which were aggravated by the colonial policies of its erstwhile rulers—became sanctified in abolitionist memory.

French abolitionists in the Société des Amis des Noirs, or society of the friends of the blacks, founded in 1788, campaigned for the rights of free people of color and the abolition of the slave trade. The French abolitionist Abbé Henri Grégoire viewed the Haitian republic, not the United States of America, as the custodian of revolutionary ideals and a beacon to the world.

The link between the Haitian Revolution and the British movement to abolish the slave trade was also intimate. British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson wrote one of the first briefs in defense of the slave rebels of Saint-Domingue in 1792 and argued for an end to the slave trade. Clarkson became an unofficial ambassador of Haiti, lobbying the French to recognize it.

American abolitionists too praised the Haitian Revolution. In his “The Rights of Black Men,” Abraham Bishop of Connecticut asked antislavery societies to assist the Haitian revolutionaries with “pen, the tongue, the counsel, the sword…and money.” The founder of the African Masonic Lodge, Prince Hall of Boston, asked enslaved blacks to look to their “African brethren” in Haiti for inspiration. Black and white abolitionists would long praise Haiti, “the glory of the blacks and the terror of tyrants.” They demanded that the United States government extend diplomatic recognition to Haiti, which the Lincoln administration finally did during the Civil War.

The best exponents of revolutionary abolition were the slaves themselves, whose world-historical actions forever changed the dynamic in the battle between slavery and freedom in the Americas. How apt it is then that, in 1994, Haiti asked UNESCO to map “The Slave Route,” to remember the victims of the slave trade and slavery—and that the U.N. has named the day that the Haitian Revolution began as abolition day. Haiti’s abolitionist heritage belongs to all of humanity.

Manisha Sinha is the author of The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition.