This piece follows up on the January 2019 post “Haitian and French Petrol Protests in the Age of Climate Change.” Since that time, the PetrolCaribe Corruption protest actions have expanded into a full-fledged movement to challenge the legitimacy of the Haitian president, and to call for the end of government corruption and the United States’ political influence in the first free Black country of the Caribbean. The protests and road blockades essentially gridlocked the country, leading government officials including the President Jovenel Moïse to warn of an impending humanitarian crisis. Today’s piece is interested in power struggles within and over Haiti, the legacy of US imperialism to be specific, through the lens of Black scholars, W.E.B. Du Bois in particular. I use Du Bois’ relationship to Haiti to explore not just the trajectory of his intellectual interests, but also to raise the question of the role of intellectuals in addressing the demands of the communities we study, especially those who have contributed so much to the world.

There are few subjects within the fields of African Diaspora Studies, Sociology, or African-American History that cannot somehow be traced to the lifelong work of W.E.B. Du Bois and his intellectual legacy. We do not commonly think of W.E.B. Du Bois and his personal interest in Haiti and the Haitian Revolution, but the first Black sovereign nation in the Americas and its revolutionary history were an important aspect of Du Bois’ thinking and activism. He understood the fundamental importance of the Revolution and Haitian freedom, and touted Haiti’s global significance as the basis for speaking out against the US military occupation of Haiti during the early twentieth century.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts on February 23, 1868. The French origin of the Du Bois name reveals W.E.B.’s paternal lineage that in part traces to the Caribbean island of Haiti. W.E.B.’s father Alfred Du Bois was born in Haiti to an unnamed Haitian woman and to Alexander Du Bois, a free Black sailor and merchant who had traveled to Haiti in the early nineteenth century after having been raised in the United States. During his first voyage in the 1820s, Alexander was likely trying to take advantage of the emigration program initiated by then President Jean-Pierre Boyer who encouraged and invited free African-Americans who were seeking land, commercial opportunities, and freedom from the constraints of racism to relocate to newly independent Haiti. The migration campaign did not survive, as many who ventured to the young country did not find it to be all that they had hoped and many returned to the United States, including Alexander who arrived in New Haven, Connecticut around 1833 or 1834 and eventually settled in Massachusetts. However, upon his return to the US, Alexander had seemingly left behind a son he had sired, Alfred, and the son’s Haitian mother. Still, by the 1860s, Alfred also made his way to Massachusetts where he met and married W.E.B.’s mother Mary Silvinia Burghardt.

“Jean-Pierre Boyer; President of Haiti (ruler of all Hispaniola after 1822), 1818-43.” (Photo: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections.)

Despite Grandfather Alexander’s short-lived voyages to and from Haiti – he’d returned briefly in the early 1860s – and subsequent estrangement between the three generations of Du Bois men, W.E.B. remained curious about his paternal lineage and undoubtedly must have been somehow impacted by his grandfather Alexander’s experience and his Haitian grandmother’s heritage. Surely the young Du Bois had heard stories of the Haitian Revolution, the Black freedom struggle, and the changing dynamics of a free black nation from oral histories. Du Bois’ connection to his paternal lineage was initially tenuous, having only met his grandfather Alexander for the first time at age fifteen during a summer visit. But according to biographer David Levering Lewis, this summer encounter with Alexander did much to elevate young William’s self-understanding and allowed him to “transform his past” through connection with transoceanic travel, Caribbean notables, and Black abolitionists (1993: 46). W.E.B.’s interest in uncovering mysteries surrounding his paternal ancestry and Haitian heritage may reflect his advocacy for Haiti during the peak years of twentieth century Haitian-US relations. Perhaps then we might consider Du Bois’ expansive vision of the Black world as having been informed, at least in part, by his personal biography.

Photo: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collection. “Mary Silvinia Burghardt Du Bois, with her sister and infant son William”

In W.E.B.’s first major composition, his 1896 doctoral dissertation The Suppression of the African Slave Trade, he places emphasis on the Haitian Revolution and its impact on slavery and the slave trade stating “the role which the great negro Toussaint, called L’Ouverture, played in the history of the United States has seldom been fully appreciated (1904 [1896]: 70).” The chapter “Toussaint L’Ouverture and the Anti-Slavery Effort” carefully traces state-level measures to end the importation of Black people from the Caribbean and to repress the trade from Africa, due to fear of Black insurrection in the fashion of the events in Haiti. At a time when the United States was embarking on its imperial projects by intervening in the Cuban Independence War and was closely eyeing political unrest in Haiti, Du Bois was arguing that the Haitian Revolution had played a significant role in the abolition of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Moreover, he was one of if not the first to identify the connections between the Haitian Revolution and the Louisiana Purchase, which helped to facilitate the expansion of plantation slavery and the growing US cotton industry. This was an important, though sometimes overlooked, contribution to the quickly growing body of scholarship about the impact of the Haitian Revolution. Other of Du Bois’ writings in The Negro (1915) and Black Folk Then and Now (1939) elevated Haiti to the place of world significance prior to writings of other Black thinkers and established its connections to important shifts related to slavery and freedom.

Du Bois’ later publications on the global Black world overlapped with the United States Marines invasion and occupation of Haiti between the years 1915 and 1934, which over time drew the ire of intellectuals and activists throughout the Black world who spoke out against the occupation at the Pan-African Congresses and League of Nations. W.E.B. Du Bois, by then working as the editor of the NAACP’s Crisis magazine, is often credited as one of the earliest voices from the United States who spoke out against the occupation, having written a letter of opposition to President Woodrow Wilson within days of the invasion. Haiti’s revolutionary history was ever on Du Bois’ mind, as his letter to Wilson extolled the country’s achievements in order to counter prevailing racist notions that the Black state was incapable of self-rule: “Hayti is not all bad. She has contributed something to human uplift and if she has a chance she can do more. She is almost the sole modern representative of a great race of men among the nations.”

Du Bois used his platform to decry the occupation throughout its duration, including at a 1929 Foreign Policy Association debate where he spoke about the importation of Jim Crow-styled racism due to the high-ranking military officers stationed in Haiti who originated from the south, the undermining of Haitian democracy, and lack of investment in Haitian education and economy. He corresponded regularly with Haitian historian and political figure Dantès Bellegarde, historian of Haiti Rayford Logan, and with the Haitian consulate in attempt to invite the Haitian president, Stenio Vincent, to visit Atlanta University.

Du Bois was a leading voice in condemning American imperialism abroad. Given the recent protest events in Haiti, one cannot help but wonder what he would say about the current state of US-Haitian relations. Surely he would be a vocal opponent to the US government meddling in past Haitian elections, domestic policies, and foreign relations – 2011 Wikileaks cables indicated that the US attempted to prevent the Venezuelan PetrolCaribe aid from reaching Haiti in the first place and wanted to keep Haiti’s minimum wage at 24 cents an hour. Du Bois likely would be reluctant to support a president that many Haitian activists and protesters now consider to be illegitimate, and would express suspicion over US military presence in Haiti.

Since the PetrolCaribe protest movement has called for Haitian President Jovenel Moïse’s resignation, many fear the return of United States military forces in the country – perhaps with good reason. A group of seven men were arrested in February 2019 by Port-au-Prince police outside of the Haitian central bank. In their possession were multiple sets of license plates, automatic rifles, pistols, drones, satellite phones, and five US passports. The five Americans were identified as members of the military industrial complex: two were former Navy SEALs, two had served in the US military, and the fifth had served as a Blackwater-trained contractor with the Department of Homeland Security. It was later reported that the men were part of a botched plan to move funds on behalf of a high-ranking government official representing President Moïse. The US State Department quickly secured the mens’ release, and they were on a flight to Miami only hours after being detained. This and other recent incidents involving American military members further stoke discontent over US support of Moïse, and raises fears of US aiding in the violent repression of protestors and apparent political control of the Haitian government.

Given such egregious actions amidst an era of global protests against corruption, austerity and rising costs of living, and neo-fascism, it is important to ask what is the role of individual scholars, and the wider academic community, in advocating for the most marginalized of the global black population? What do we owe Haiti specifically, considering its contributions to humanity? What do scholars owe their subjects of study, especially during their times of crisis? What does solidarity look like in these days and times? Du Bois’ life, intellectual legacy, and activism continues to be a lens through which we consider our social responsibility as scholars and activists.

Crystal Eddins is an Assistant Professor of Africana Studies at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and the 2018-2019 Ruth J. Simmons Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for the Study of Slavery & Justice at Brown University. She holds a Dual Major PhD in African American & African Studies and Sociology from Michigan State University. Eddins’ areas of research are the African Diaspora, Historical Sociology, Social Movements, the Digital Humanities, and 18th century Haiti (Saint Domingue). Follow her on Twitter @CrystalNEddins.

Source: AAIHS

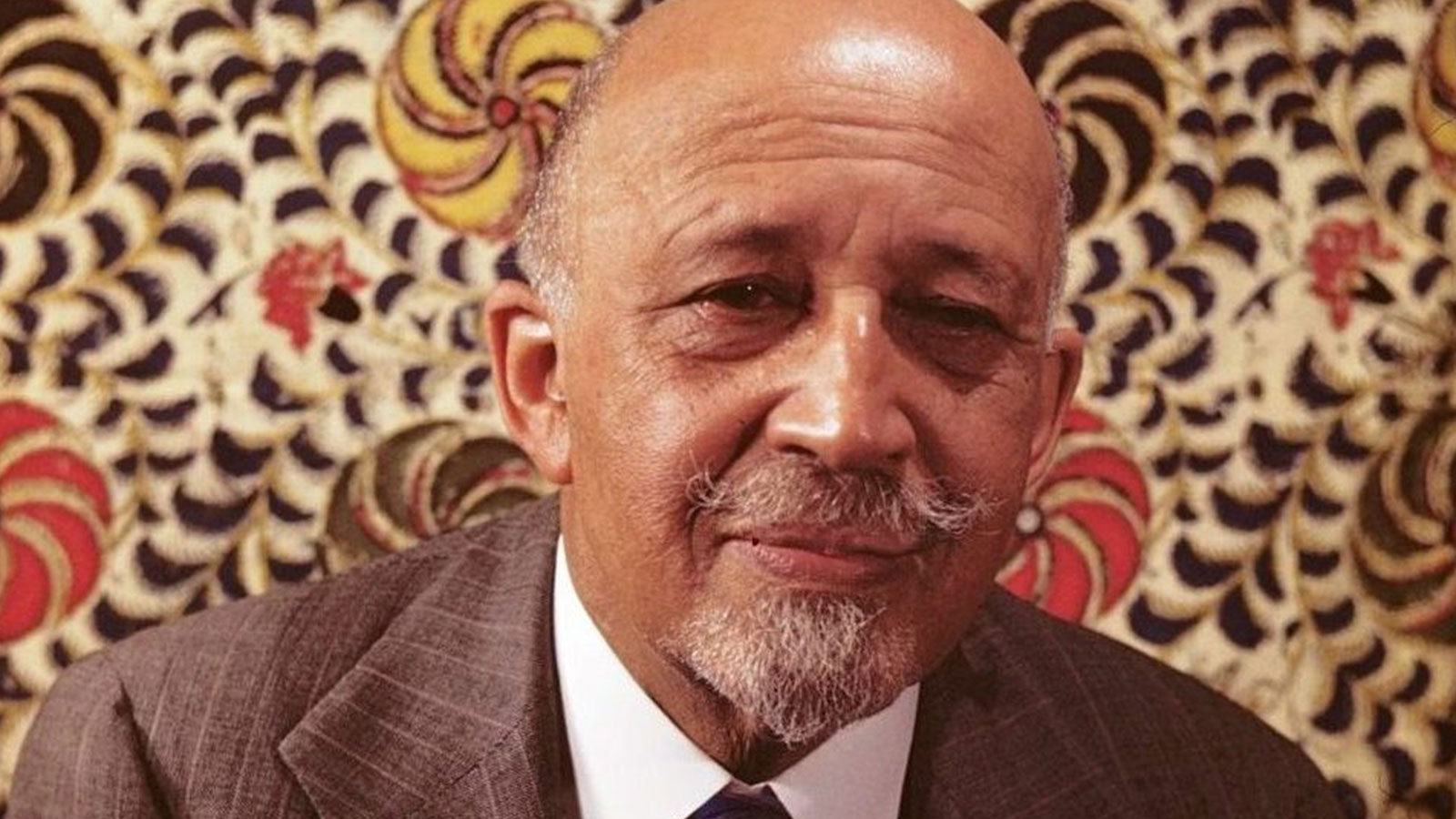

Featured image: W.E.B. Du Bois, ca. 1946. (Photo: Flickr; Van Vechten Photographs, Yale University)