Fifty years ago, Martin Luther King Jr. and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference took on a new challenge: expose and overcome racial discrimination in Chicago. Here, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, author of From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation, explains the backdrop to this new struggle of the civil rights movement and tells the story of a challenge to institutional racism in 1960s America’s second-largest city.

THE MAIN goals of the Southern civil rights movement included ending Jim Crow and securing the right of African Americans to vote across the South. Federal legislation guaranteeing both of these, in 1964 and 1965 respectively, signaled victory for the movement.

But the end of legal discrimination in the South only heightened the growing awareness about inequality across the North. Indeed, Malcolm X had pointed out that the conditions experienced by Black people in Northern ghettos rivaled the conditions faced by African Americans in the South. As he wrote in his autobiography:

The Deep South white press generally blacked me out. But they front-paged what I felt about Northern white and black Freedom Riders going South to “demonstrate.” I called it “ridiculous”; their own Northern ghettoes, right at home, had enough rats and roaches to kill to keep all of the Freedom Riders busy. I said that ultra-liberal New York had more integration problems than Mississippi…The North’s liberals have been for so long pointing accusing fingers at the South and getting away with it that they have fits when they are exposed as the world’s worst hypocrites.

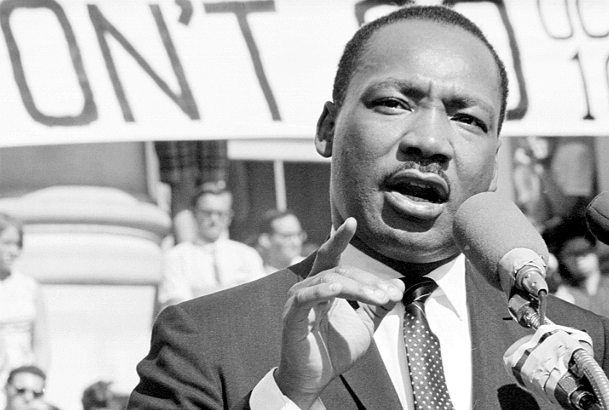

A year after the assassination of Malcolm X, civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. would shift the attention of his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), from its campaigns across the South to the developing movement in the North.

It was not mainly chastising from Malcolm X that created awareness about racism, poverty and inequality across the urban North. In the summers of 1964 and 1965, urban riots and rebellions dramatized conditions in Black ghettos for the nation and the world to see.

In cities as disparate as Rochester, New York; Philadelphia; Harlem in New York City; Jacksonville, Florida; Patterson, New Jersey; and South Central Los Angeles, Blacks rebelled against poverty, underemployment, substandard housing and rampant police violence and abuse. When the Watts section of LA ignited only a few days after the Voting Rights Act was to take effect, it symbolically shifted the focus of the Black movement from the South to the North and West.

The Watts Rebellion in the summer of 1965 was the largest of its kind. It was shocking in its destruction and devastation, but also in the combative reaction of local Blacks.

King traveled to Watts to assess the damage and was stunned by the attitude of local youth, who claimed the rebellion as a “victory” because it brought attention of the world on to the racism experienced by Blacks in LA. King came to understand the Watts Rebellion as a local expression of a worsening economic and political situation for the great mass of Black people across the country. He wrote:

Let us not assume that this is a situation peculiar to Los Angeles alone. It is a national problem. At a time when the Negro aspirations are at a peak, his actual conditions of employment, education and housing are worsening. The paramount problem is one of economic stability for this sector of our society. All other progress, in education, family life and the moral climate of the community is dependent upon the ability of the masses of Negroes to earn a living in this wealthy society of ours.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

SOME FIVE months after the Watts uprising, King arrived in Chicago in January 1966 and announced “the first significant Northern freedom movement ever attempted by major civil rights forces.” King declared the focus of the movement would be the “unconditional surrender of forces dedicated to the creation and maintenance of slums.”

King came to Chicago by the invitation of activists who formed the core of the Chicago Freedom Movement (CFM). They had been the key organizers of boycotts and campaigns in 1963 for the struggle against public school apartheid in the city.

Chicago activists debated whether to focus on job discrimination or racism in public schools. Eventually, King, organizers from SCLC and local activists agreed on a target: slum conditions in housing on the West Side of Chicago. They concluded that the problems in housing were closely tied to problems of access to jobs and good schools. To dramatize the point, King moved into a shabby apartment on the city’s segregated West Side as the campaign began to set up.

The campaign was to lead to the creation of “Unions to End Slums” across the city. This was part of a collaborative effort between the AFL-CIO and SCLC to use the “union model” to organize tenants and expose conditions of poverty in cities across the country.

For their part, union leaders were attempting to regain favor among a growing layer of African American workers who were bitter about racism in the labor movement. Black workers often held the most physically difficult and worst-paid jobs in union shops–and growing numbers of them were critical of union officials. The civil rights agenda of unions like the United Auto Workers were intended to offset criticism of the internal politics of the organizations.

Nevertheless, the Unions to End Slums took off in Black communities across Chicago. From 1966 through 1969, tenant unions sprang up on both the West Side and South Side. They challenged high rents and miserable building conditions–and, most importantly, forced landlords and owners to sign collective bargaining agreements that linked payment of rent to apartment conditions.

It may seem remarkable today, but tenant unions across Chicago in the late 1960s compelled landlords who owned thousands of apartments to sign agreements. Through a combination of picketing, sit-ins, rallies and rent strikes, the Chicago tenants movement publicized the slum conditions that were ubiquitous in poor Black neighborhoods across the city–and landlords frequently bowed to the pressure.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

TENANT UNIONS typically formed when activists surveyed residents in their buildings about which conditions bothered them most. These surveys became the basis of the bargaining agreements with landlords. Tenant activists also held hearings about building conditions and invited landlords to defend themselves against charges of being slumlords.

As early as 1966, the East Garfield Park Union to End Slums was successful in compelling West Side slumlords into signing a collective bargaining agreement that allowed 1,500 tenants to withhold rent and named the union as their sole bargaining agent. This one-year agreement was the first of its kind in Chicago.

In August 1967, when it was time to renew the agreement, the landlords decided to sell the building rather than sign a new contract with reduced rent. The new owners quickly signed the contract for fear of a rent strike. The landlords agreed that rent payments would be tied to conditions, and that tenants would have the right to withhold payment if the building went into disrepair.

There was another dramatic struggle over tenant rights in 1966 when the Tenants Action Council (TAC) formed to fight landlord conduct in a housing complex in the Chicago neighborhood of Old Town. Black and white tenant-members of TAC were determined to resist their landlord, who used the common tactic of allowing building conditions to deteriorate so that white tenants would leave and be replaced by Black tenants paying higher rents.

When the landlord attempted a mass eviction, TAC initiated a rent strike, leading to a highly publicized confrontation in September 1966. According to the Chicago Tribune, hundreds of protesters and tenants faced off against 80 police officers. While crowds jousted with the police outside of the building, TAC members inside chained themselves to radiators and refused to leave, often taking shifts with other tenant-members.

Wherever the Cook County Sheriff’s deputies succeeded in removing the possessions of some tenants, TAC members and supporters gathered their belongings and returned them to the emptied apartments.

After about a week of these confrontations, building owners relented and agreed to sell the building to a buyer who would sign TAC’s collective bargaining agreement. The deal that ended the rent strike and protest included an agreement to stop all litigation against tenants who had participated in the strike.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

THESE BATTLES represent just a fraction of the tenant union and rent strike activity of that era. From 1966 to 1969, the conservative Republican newspaper, the Chicago Tribune, published more than 100 articles about tenant unions, rent strikes and the conditions that produced them.

In 1969, the Chicago Defender reported on a survey showing that in the first eight months of that year, tenant organizations “took action 67 times in 23 cities” against slum conditions and the absence of rights for tenants.

However, maintaining the tenant unions became increasingly difficult. Landlords brazenly used the lack of rights for tenants to simply evict renters who withheld rent. Moreover, because of slum conditions, there was high turnover in the housing as people moved out of their buildings as soon as they could. This inevitably created instability and turnover in the tenant unions.

As a result of this turnover, the SCLC focus on the Unions to End Slums quickly turned to “fair” and “open” housing as an alternative. King was preparing to transition the movement’s focus from slum housing to racial discrimination in the real estate industry in Chicago. He called it “Operation Equality.” Here, King and his lieutenants in the SCLC would look to instigate the kind of confrontation between movement activists and white racists that spurred the Southern movement.

While tenant unions had focused on conditions in the inner cities and the buildings where Black people lived, the focus on fair and open housing looked to dismantle the barriers that kept African Americans out of white suburban areas and white neighborhoods in the cities.

The CFM organized marches into hostile white neighborhoods hoping that a confrontation with white racists would spur the city into action. While these actions received a lot of publicity from the media and political detractors, the marches were never very big–Black Chicagoans were not interested in living in neighborhoods where whites wanted to kill them.

Moreover, the shift to focus on fair housing all but ignored the issue of combating the racist conditions of discrimination and exclusion in African American neighborhoods on the South and West Sides of Chicago. In other words, activists asked why African Americans should have to move to white neighborhoods in order to get access to good housing, good jobs and good schools?

Clearly, Black people should be able to move wherever they would like. But the focus on fair housing failed to address the lack of resources in African American neighborhoods in the cities.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

IN AN attempt to straddle the tensions in the movement–between addressing concerns within segregated Black neighborhoods and challenging local fair housing laws–the CFM organized a “freedom rally” at Soldier Field in downtown Chicago on July 10, 1966. King addressed 55,000 people–mostly African Americans to outline the demands CFM would look like. In his speech, King said:

This day, we must declare our own Emancipation Proclamation. This day, we must commit ourselves to make any sacrifice necessary to change Chicago. This day, we must decide to fill up the jails of Chicago, if necessary, in order to end slums. This day, we must decide to register every Negro in Chicago of voting age before the municipal election. This day, we must decide that our votes will determine who will be the mayor of Chicago next year…This day, we must continue our already successful efforts to organize, in every area of Chicago, unions to end slums. Together, we must withhold rent from landlords that force us to live in subhuman conditions.

And let me say, here and now, that we are not going to tolerate moves that are now being made in subtle manners to intimidate, harass and penalize Negro landlords who may own one or two buildings, while ignoring the fact that slums are really perpetuated by the huge real estate agencies, mortgage and banking institutions, and city, state and federal governments.

After the speech, 5,000 people accompanied King to place a list of demands on the front door of City Hall. Part of the CFM’s goal was to highlight the unequal living conditions in African American communities created by the existence of slum conditions. Some of the demands included:

– Creation of a citizens review board for grievances against police brutality and false arrests or stops and seizures.

– An ordinance giving ready access to the names of owners and investors for all slum properties.

– A saturation program of increased garbage collection, street cleaning and building inspection services in the slum properties.

– A program to vastly increase the supply of low-cost housing on a scattered basis for both low and middle-income families.

– Prepare legislative proposals for a $2 an hour state minimum wage law and for credit reform, including the abolition of garnishment and wage assignment.

– An executive order for Federal supervision of the nondiscriminatory granting of loans by banks and savings institutions that are members of the Federal Deposit Insurance.

The Chicago Tribune denigrated the march and the entire desegregation campaign in Chicago, writing, “We suppose that ‘civil rights’ spokesmen will engage in these charades just as long as there are publicity and a chance of passing the hat.” Mayor Richard Daley went so far as to insist that there was no segregation or slums in the city of Chicago.

The CFM’s plan of creating chaos and havoc in the city was met each time by racists who confronted marches that challenged the racialized neighborhood boundaries throughout Chicago.

When King and civil rights marchers marched through Marquette Park, thousands of white racists challenged the activists and threatened them with physical harm. Indeed, one placard at the march read, “King would look good with a knife in his back.” King was one of 40 people injured in the march. He went on to observe, “I have seen many demonstrations in the South, but I have never seen anything so hostile and so hateful as I’ve seen here today.”

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

FOR WHATEVER it was worth, these marches helped to demonstrate to the rest of the country that racism in the U.S. was no regional phenomenon. Chicago at this time was the second-largest city in the United States, and Black achievement and quality of life were still tightly constrained by pervasive and suffocating racial discrimination in every facet of life.

The deep and institutional character of racial discrimination in Chicago was even baffling to King. There would be no significant victories won in Chicago. Just exposing racism to be a fact of life outside of the South wasn’t enough to actually change those conditions. The intransigence of the racist structures governing Black life in Chicago certainly contributed to the radicalization of King and his turn to emphasizing the “radical reconstruction” of all of American society as a cure for its inequality ills.

In the end, King’s foray into Chicago politics quietly came to an end when the CFM and city officials agreed to a series of toothless pledges and promises to end discrimination in real estate and banking, and to allow for unfettered Black access to the entire Chicago housing market. Of course, none of these measures included any enforcement language or guarantee–just the promise to do better.

Fifty years later, Chicago’s landscape remains marred by strict residential segregation–and with it, persistent unemployment, poverty and under-resourced public institutions. Then as now, police violence and abuse is all that city leaders can muster as a response to the lack of resources and the Black public outcry as a result.

Chicago needs a new freedom movement to continue the struggles that were not resolved 50 years ago, and now have become even more severe.