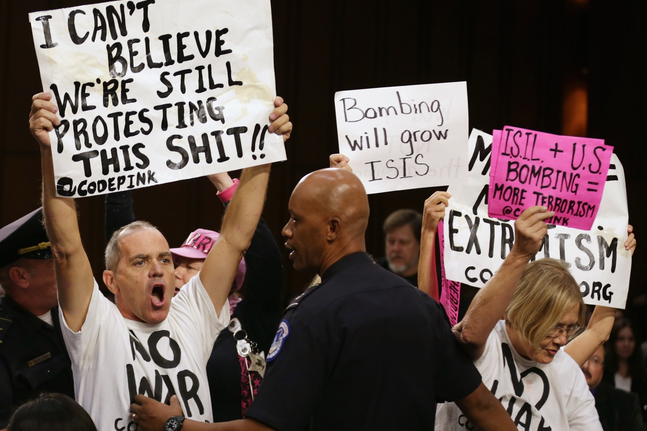

Protesters from CODEPINK interrupted a hearing on the war against ISIS. (Photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

By Alex Kane

When President Obama said he intended to strike Syria last year after the Assad regime launched a chemical weapons attack, anti-war sentiment surged in the U.S. Phone calls and e-mails poured into Congressional offices with one message: don’t bomb Syria. The president eventually backed off from his plan after agreeing to a Russian proposal that saw President Bashar al-Assad get rid of his chemical weapons.

One year later, the administration declared war on the Islamic State, the Sunni extremist group that has taken over territory in Syria and Iraq. Warplanes have repeatedly hit targets in Iraq and Syria, and the U.S. is reportedly considering a no-fly zone over Syria. But this U.S. war is commencing with no serious opposition to slow the president down.

The anti-war movement is struggling to gain traction in the face of headwinds that include fear over the Islamic State, or ISIS, a media incessantly broadcasting news of ISIS atrocities and the loss of one obvious leverage point: Congress. Last year, Obama tossed the ball to Congress on the question of whether to attack the Assad regime. This time, though, there has been no Congressional vote on whether the U.S. should bomb Syria and Iraq. The president did it anyway in a move criticized by some legal analysts.

There has been no big demonstration to call attention to anti-war sentiment, though groups have held dozens of small actions.

For now, polls show that the American people are backing U.S. intervention, though they don’t want U.S. troops to be sent to Syria or Iraq. (At least 1,600 soldiers are already in Iraq in what the administration says is an “advisory” role.)

Anti-war organizers say that the beheadings of two American journalists–James Foley and Steven Sotloff–by ISIS are the principal reason why there’s widespread support for the intervention.

“It’s always hard in the beginning of a war when you have all of the hype about how awful the enemy is, and the enemy is always awful. and certainly ISIS is no different–it’s horrible just like Saddam Hussein was horrible, just like Al Qaeda is horrible and the Taliban is horrible,” said Medea Benjamin, the co-founder of CODEPINK, a group that has been visibly active against the new U.S. bombing campaigns. “The beheadings are particularly impactful on people’s sense of outrage.”

Adding to the anti-war movement’s difficulties is that “this is a different fight than the ones we’ve had before…it’s a much more complicated situation, it requires much more public education, much more understanding the issue,” said Stephen Miles, the advocacy director of Win Without War, a coalition of about 40 progressive groups.

Organizers also say that media outlets have played a big role in encouraging support for war. Some prominent figures like MSNBC’s Chris Matthews have voiced skepticism and opposition about American intervention. But that’s more the exception than the rule. “War time is when TV screens are full of former generals and hawkish politicians, and reporters are busy transmitting official claims,” wrote Peter Hart, Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting’s activism director, in a September blog post criticizing media coverage of the intervention against ISIS.

Compounding these obstacles for the anti-war movement is that the election of President Obama in 2008 deflated activism in opposition to Middle Eastern wars. CODEPINK’s Benjamin said that the decrease in peace activism can be attributed to a focus on domestic issues, frustration at the inability to change U.S. foreign policy, Democratic support for the president and Obama’s opaque drone wars. “We’ve never been able to have a big demonstration, anti-war demonstration, ever since Obama came into office. So that’s number one–the whole peace movement is really a shadow of what it was under Bush,” she said.

But even though organizers acknowledge the uphill battle, some say there’s cause for optimism. There was some Congressional opposition to arming Syrian rebels to fight the Islamic State. The authorization to help rebels passed the House by a 273-156 vote; the Senate opposition amounted to only 22 votes.

“This war is far less popular than either the Afghanistan or Iraq War at their outset at this time period. And it’s worth remembering that inevitably what happens, no matter where these wars start, they always end at the same place, which is incredibly unpopular,” Win Without War’s Miles told me.

So where does the anti-war movement go from here? Ali Issa, the national field organizer with War Resisters League, says the key is connecting struggles against militarism to other movements. War Resisters League has been linking police militarization in the U.S. and war-making worldwide. He cited the “multi-racial, cross-movement coalition” that opposed Urban Shield, an annual international weapons expo featuring SWAT training. The event also sees arms vendors showing off their wares to police departments around the country and globe. After protests were held, the mayor of Oakland announced that Urban Shield would no longer be held in the city.

“If we take this experience as a lesson for how to address the recent U.S. military escalation, that can provide a model for how the anti-war movement builds across communities,” he said. “Without strategic organizing centered on relationship building, it’s going to be hard to break through the pro-war media noise which exists to shock and awe us.”