By Christopher Petrella and Justin Gomer —

A *few weeks ago, we convened and moderated a “justice and equity” reading group for students, staff, and faculty at a local college. Our inaugural meeting centered on an essay in which the author calls attention to the shortcomings of organizing racial justice interventions in higher education around the sanitized and depoliticized language of “diversity.”

While nearly every participant agreed that programs and initiatives captured under the banner of “diversity” would fail to remediate historical and contemporary racial wrongs, we quickly noticed something else: a number of white discussants began describing racism as a “disease,” as a “mental illness,” and as a form of “deviant behavior.” In a private conversation after the gathering, one staff member approached us with the suggestion that we should consider “lobotomizing the racists that hold our country back.”

The subtext was palpable: racism is little more than a behavior-based psychopathology that discloses itself in discrete manifestations of bigotry, prejudice, and misunderstanding. According to such a construction, racism can only be treated with medical intervention. Racial inequity, therefore, is simply the sum of the actions of individual bigots and racial justice can be achieved by “curing” those individuals.

The presumption that one can eliminate racism by snuffing out a few “bad apples” misses the mark. In fact, such a paradigm misdiagnoses the systemic and ideological production of race itself which is squarely centered in white supremacy.

The “racism as disease” paradigm only seems to make sense if one were also to believe that racism is 1) a matter of (mis)recognition and (mis)perception meted out in an apolitical and behaviorist colorblind present; 2) an unfortunate holdover from slavery, a past mistake that has yet to be rectified; and 3) an anomaly; a radical deviation from the telos of dominant political institutions and practices.

Such a psychopathological paradigm, however, is not an appendage of nineteenth century scientific racism but rather twentieth century liberal social science. In An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (1944), Swedish Nobel-Laureate economist Gunnar Myrdal argued that “[racism] is a terrible and inexplicable anomaly stuck in the middle of our liberal democratic ethos.” His popular study — funded by the Carnegie Foundation — provides a forceful, if incomplete, framework for explaining the persistence of racial injustice in the United States. Myrdal’s book quickly became an authoritative text for defenders of racial integration in the postwar period and his work gained popularly in the US imagination after it was cited in Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Together, Myrdal’s study and the Brown decision helped to shift race discourse away from systemic critiques of white supremacy emblematized by DuBois’s The Souls of Black Folk (1903) to diagnoses based on “psychological knowledge” and personal attitudes. Addressing and eliminating quantifiable racial inequities gave way to treating individual racists (i.e. the few “bad apples”) in an otherwise racially just country. Structural white supremacy, in other words, became conflated with individual bigotry.

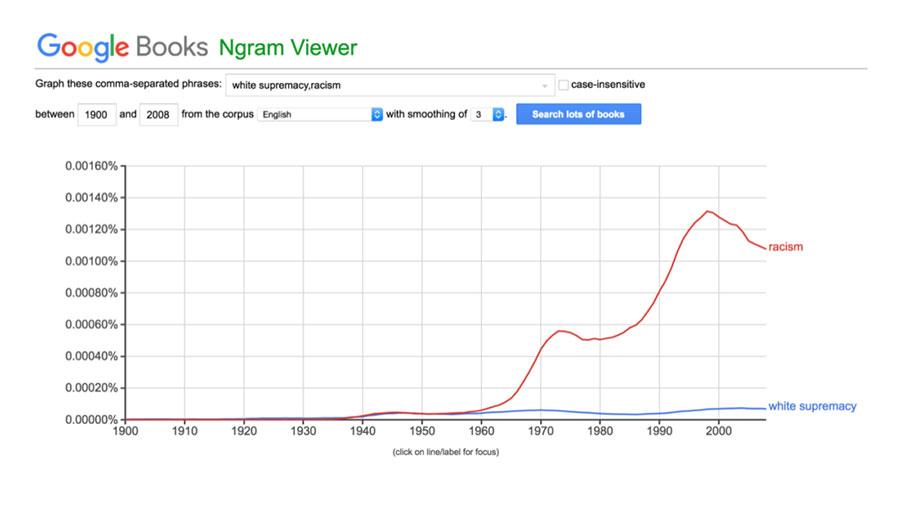

Google Books Ngram tracking usage of “white supremacy” and “racism” from 1900-2008. (Image: Google)

Consider the Google Books Ngram depiction above. From 1900 to the mid-century, the terms “white supremacy” and “racism” were both used at a similar rate in popular and scholarly usage. Beginning in the late 1950s, however, “racism” began to surpass “white supremacy” as the preeminent term for marking, diagnosing, and ameliorating various forms of racial injustice. The deficiency of this term rests in its ability to invisibilize both its locus and its origin: whiteness. Avoiding the term “white” overlooks the policies, practices, and hierarchies of domination and exclusion that has shaped US and global history.

Myrdal’s study continues to set the parameters of mainstream race discourse in the United States. His anomaly thesis casts racism in the vernacular of deviance and abnormality, providing the discursive basis for thinking about racism as illness or disease.

White supremacy, however, is unexplainable by the anomaly thesis. In School Desegregation (1984) scholar Jennifer Hochschild rightly argues that “racism is not simply an excrescence on a fundamentally healthy liberal democratic body…Liberal democracy and racism in the US are historically, even inherently, reinforcing; American society as we know it exists only because of its foundation in racially based slavery, and it thrives only because racial discrimination continues. The apparent anomaly is an actual symbiosis.” White supremacy is not an unfortunate, anomalous stain on an otherwise virginal tapestry of democracy but rather, to paraphrase Hannah Arendt, it’s terribly, terrifyingly normal.

In fact, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) has for decades admitted that racial injustice is too normal to be considered a mental illness or a disease. In 1969, a group of black psychiatrists urged the organization to acknowledge that racism is the “major mental health problem of this country” and to include extreme bigotry as a recognized mental illness in the Diagnostics and Statistics Manual (DSM). Though the APA endorsed the “general spirit of reform and redress of racial inequities in American psychiatry” it rejected the psychiatrists’ desire to classify extreme bigotry as a mental illness. In order for racism to be considered a mental illness, the APA declared, racism must deviate from normative behavior. Because racism is ubiquitous, it could not constitute a mental illness. The APA used this rationale to keep racism out of the DSM in 1980, 1987, 1994, and 2013.

The ideology of race itself leads back to whiteness and white supremacy. US immigration and naturalization legislation, race-based marriage statutes, inheritance law, redlining, and the segregation of public facilities are all examples of how whiteness informs policy and practice. They draw, secure, police, and legitimize the parameters of whiteness and non-whiteness.

So-called anti-miscegenation statutes reinforce this argument. From a strictly etymological perspective “anti-miscegenation” most closely refers to a proscription against “race-mixing” in marriage or conjugal entanglements. The term, however, does not accurately depict the ideological underpinnings of the law. Most anti-miscegenation laws, in fact, did not prohibit marriage or sexual relations between two non-white people. What architects of anti-miscegenation laws feared most was race-mixing between white and non-white people because such a social practice would compromise the prospect of white racial purity, white national purity, and global white supremacy. Similarly, US naturalization law from 1790 to 1952 carried with it an explicit prerequisite of whiteness. For instance, the first US Immigration and Naturalization law (1790) restricted naturalized citizenship to “a free white [male], who shall have resided within the limits and under the jurisdiction of the United States for the term of two years.”

Ultimately, framing white supremacy as exceptional, individualized, and through the language of disease obscures its origins and movements. As George Lipsitz argues, “Whiteness has a cash value” that produces advantages and “profits” for white people in virtually all areas of social organization including housing, education, employment, and intergenerational wealth. Lipsitz continues, “white supremacy is usually less a matter of direct, referential, and snarling contempt than a system for protecting the privileges of whites by denying communities of color opportunities for asset accumulation and upward mobility” and access to full and legitimate citizenship.

Those who continue to explain racial injustice through appeals to disease or illness implicitly reinforce a discourse that misdiagnoses the machinations of white supremacy. If we are truly to craft an antiracist politics capable of threatening the endurance of white supremacy, we must reject analyses and interventions that individualize social injustice by relying on notions of disease, mental illness, or deviance.

*Note: This article was originally posted in December 2016

Justin Gomer, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of American Studies at California State University, Long Beach. Follow him on Twitter @ProfessorGomer.

Christopher Petrella is a lecturer at Bates College in Lewiston, Maine, and a teaching fellow at Harvard University. He writes on race, incarceration and capitalism. His work is curated at ChristopherFrancisPetrella.net