A new study offers two answers: White people are making up a smaller percentage of the population than they used to, and different races are living in different school districts.

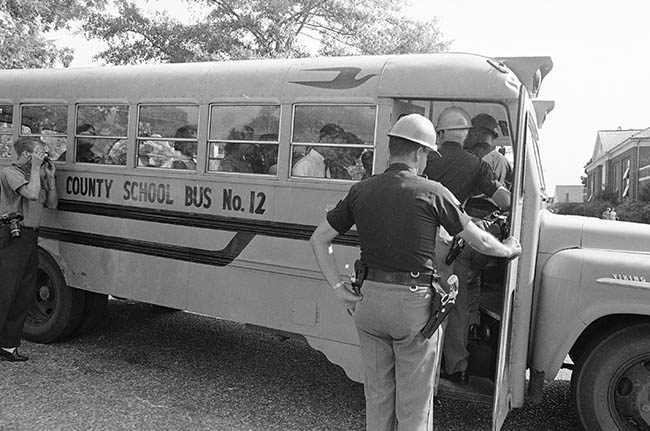

Fifty years ago this fall, Alabama state troopers turned away a bus with 13 black students who were on their way to the all-white Tuskegee High School. (Associated Press)Jeremy Fiel grew up going to fairly diverse public schools in Lubbock, Texas. “Some schools had a higher black or Hispanic population,” he said. “But there weren’t any all-white schools.” After graduating college in 2006, he spent three years teaching science in Greenwood, Mississippi. What he saw in Greenwood shocked him.

Fifty years ago this fall, Alabama state troopers turned away a bus with 13 black students who were on their way to the all-white Tuskegee High School. (Associated Press)Jeremy Fiel grew up going to fairly diverse public schools in Lubbock, Texas. “Some schools had a higher black or Hispanic population,” he said. “But there weren’t any all-white schools.” After graduating college in 2006, he spent three years teaching science in Greenwood, Mississippi. What he saw in Greenwood shocked him.

“Segregation there was the most extreme I’ve ever seen,” said Fiel. “There were literally less than five white kids in an entire public school.”

Fiel’s experience as a teacher inspired him to go to graduate school in sociology to study segregation and inequality in education. Now a Ph.D. candidate at University of Wisconsin–Madison, Fiel recently published a study in theAmerican Sociological Review that suggests the factors driving segregation have increased in scale in the past several decades—and that fixing the problem will require a new set of strategies.

Nearly 60 years after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision that ordered school districts to desegregate, schools seem to be trending back toward their segregated pasts. In the 1968-69 school year, when the U.S. Department of Education started to enforce Brown, about 77 percent of black students and 55 percent of Latino students attended public schools that were more than half-minority. By the 2009-2010 school year, the picture wasn’t much better for black students, and it was far worse for Latinos: 74 percent of black students and 80 percent of Latino students went to schools that were more than half-minority. More than 40 percent of black and Latino students attended schools that were 90 percent to 100 percent minority.

Related Story

American Education Isn’t Mediocre—It’s Deeply Unequal

The persistence of segregation is a problem because, today as in the Brown era, separate schools are unequal. “Schools of concentrated poverty and segregated minority schools are strongly related to an array of factors that limit educational opportunities and outcomes,” wrote the authors of a 2012 report by the University of California–Los Angeles’s Civil Rights Project. “These include less experienced and less qualified teachers, high levels of teacher turnover, less successful peer groups and inadequate facilities and learning materials.”

Fiel’s study found that one factor that’s led to the decline of white students in minority-heavy schools is the fact that white people make up a smaller proportion of the overall student population:

Jeremy E. Fiel, American Sociological ReviewWhites are nearly a minority in the U.S. population under the age of five, and Census projections predict that by 2043, whites will no longer be the majority of the U.S. population overall. “There’s going to be fewer whites in minority schools because there are fewer whites in the population,” said Fiel.

Jeremy E. Fiel, American Sociological ReviewWhites are nearly a minority in the U.S. population under the age of five, and Census projections predict that by 2043, whites will no longer be the majority of the U.S. population overall. “There’s going to be fewer whites in minority schools because there are fewer whites in the population,” said Fiel.

Another part of the problem is with desegregation policies themselves. At the time of the Brown decision, schools in the same district were vastly unequal to one another, so efforts went toward integrating schools within each district. That made sense to combat segregation as it existed at the time.

Today, though, Fiel found that racial imbalance tends to exist between school districts, rather than within them. This chart shows how different factors have contributed to racial isolation over the past decade. Racial imbalance between districts (the black bar) has consistently played the most significant role in nearly all forms of racial isolation:

Jeremy E. Fiel, American Sociological ReviewThis map of school districts in and around New York City is a good illustration of this phenomenon:

Jeremy E. Fiel, American Sociological ReviewThis map of school districts in and around New York City is a good illustration of this phenomenon:

National Center for Education StatisticsThe darker the green, the larger the the black population in the school district. Notice that there are several dark-green (i.e. majority black) districts bordering off-white (i.e. majority white) ones. The Mount Vernon City School District near New Rochelle, for example, has a 62.1 percent black population. On its northern border lies a little off-white dot: the Bronxville Union Free School District, whose population is 0.6 percent black. Student achievement in those districts is similarly divergent: In Mount Vernon, 68 percent of students pass New York State’s high-stakes Regents exam; in Bronxville, 100 percent pass. You can see other, similar contrasts near Newark (on the southwestern side of the map) and on Long Island (on the eastern side).

National Center for Education StatisticsThe darker the green, the larger the the black population in the school district. Notice that there are several dark-green (i.e. majority black) districts bordering off-white (i.e. majority white) ones. The Mount Vernon City School District near New Rochelle, for example, has a 62.1 percent black population. On its northern border lies a little off-white dot: the Bronxville Union Free School District, whose population is 0.6 percent black. Student achievement in those districts is similarly divergent: In Mount Vernon, 68 percent of students pass New York State’s high-stakes Regents exam; in Bronxville, 100 percent pass. You can see other, similar contrasts near Newark (on the southwestern side of the map) and on Long Island (on the eastern side).

“The biggest barrier to reducing racial isolation…is racial imbalance between school districts in the same metropolitan area/nonmetropolitan county,” Fiel wrote in his American Sociological Review article.

Inter-district segregation does not come with an easy solution. Creating integrated schools in these areas would require students to travel across district lines—a form of desegregation policy that has been struck down by the Supreme Court.

“We need new policies and new ways of addressing segregation because it’s on a much larger scale now,” Fiel said.