Nija Guider, 21, spent three days in a Georgia jail ― locked away from her infant son ― because she attended a party where marijuana was present.

Meanwhile, in states across the country, businesses, many run and funded by wealthy white men, stand to make millions of dollars selling the federally illegal substance.

It is easy, amid the fog of flippant news coverage and caricatured weed culture, to mistake America’s stance on marijuana. Our parlance concerning cannabis use is decidedly more humorous than our actual posture toward it, with playful stoner parodies and punny news segments affording the nation a veneer of tolerance.

Twenty-nine states, including Arkansas, Florida and West Virginia, have legalized cannabis in some form. But neither the rewards of cannabis nor its tremendous risks are dispersed evenly among its users and distributors. Some have the luxury of imagining the cannabis plant and its surrounding industries romantically, while others must acknowledge it for what it is ― a Schedule 1 drug subject to life-altering scrutiny by law enforcement.

While we’ve given a great deal of focus to the ways this disparity impacts black men, black women are also harmed disproportionately.

Throughout the country, in red states and blue states, black women have been arrested for marijuana at higher rates than both white men and white women.

In Atlanta, for example, research from a city councilman found black women accounted for twice as many weed arrests as white men in 2016, and seven times as many as white women. In San Francisco, a recent study found black women comprised 30 percent of felony weed arrests in 2013, despite making up only 6 percent of the total population.

There is a caste borne of this inequality, with a seemingly ever-growing class of enterprising white men superseding, among others, a class of black women whose entanglement in the justice system forebodes grave things for the households they head.

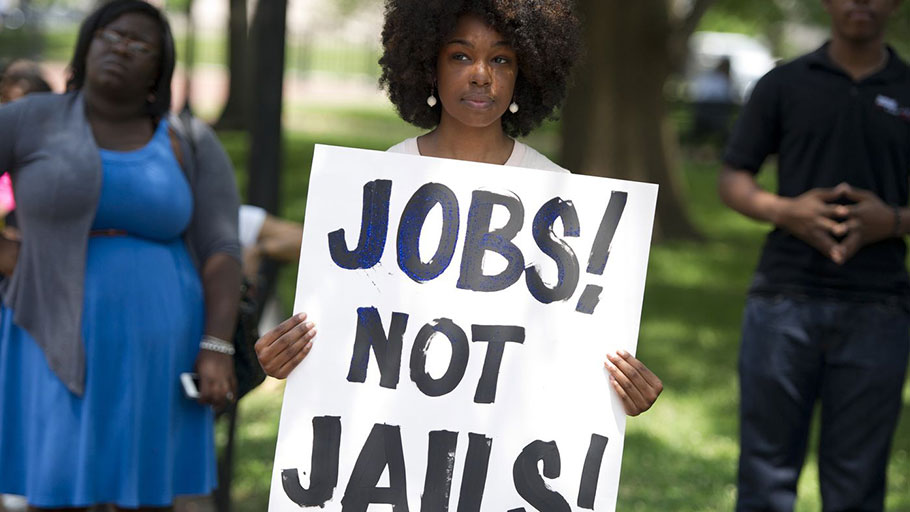

A demonstrator holds a sign during a 2013 rally following a protest march calling on former President Barack Obama to end the so-called War on Drugs. Photo: Saul Loeb, Getty Images

In the early hours of New Year’s Day, news broke of a mass arrest of partygoers in Cartersville, Georgia, a suburb not far from Atlanta. The bust snagged at least 63 attendees (most of them black) at a birthday party for 21-year old Deja Heard. Officers found less than 1 ounce of marijuana, the Cartersville Daily-Tribune reported. Nobody confessed to owning the drug, and each of the 63 arrested was initially charged with possession because the drug was “within everyone’s reach and control,” the Bartow Cartersville Drug Task Force said in a news release.

The incident had plenty of symbolism. In this predominantly white suburb of Cartersville, the optics of officers descending on a party of black attendees and levying stringent drug law ― for a plant legally enjoyed in 29 states ― against a great many inspired dismay in progressive circles across the nation.

Some advocated on behalf of those arrested. But their good intentions could not save Guider and many of her fellow party attendees from the implications of that evening.

Over the phone, Nija Guider’s voice carries an authority that defies her age.

At 21 years old, she navigated seamlessly between relaying stories of her crippling stint in a Cartersville jail and returning blown raspberries to her 1-year-old son, Isaiah.

“You sit up there and look at a man who’s doing his job,” Guider said of supervising officers at the county jail, “while you can literally feel your life turning to shambles. You can feel it.”

Guider, a close friend of Heard, said she doesn’t smoke weed. But the sweep that night left Guider and more than 20 other women from the party crammed in a single holding cell nonetheless.

Guider said that until she was guided through the rigmarole of jail booking, she believed she’d return home that evening.

I’m looking at it as, ‘I shouldn’t be going through all this.’ Nija Guider

“‘Maybe we’re just going to go up to the jail and all of our parents are going to get us’ ― that’s what I was thinking. But when we got to the jail, and when they started making us do the little squat and cough, I was like, ‘Yep, we’re in,’” she said.

As she recollects, Guider manages a tragic chuckle, suggesting she should have known better.

From there, she remembered distinctly the yells from nearby holding cells, in which dozens of men collected from that night’s party clamored, offering to accept drug possession charges in return for their release.

“I’ll take the charge! I want to go home, I want to go home!”

Guider remembers the police responding, “It’s too late.”

For so many reasons, and for so many people that evening, it was.

It is responsible to view willful, false admissions of guilt to avoid jail time as a failure of our rehabilitative techniques. Ideally, jails are not petri dishes used for testing the resiliency of innocent people against self-harm.

But in speaking with Guider, it’s clear how such a frenzy can occur. When a person’s lifeblood is withheld, they will stop at nothing to reach it again.

When Guider thought of her son, she too realized the lengths to which she’d go to reunite with him once more.

“There was nothing I wouldn’t give to wake up and hold my child like I normally do at home,” she said.

During the three days she spent in jail on alleged weed possession, Guider’s life was effectively ruined. That’s not to say her life cannot be rebuilt, but rather that the time and energy she’ll have to dedicate to doing so disadvantages her when compared to others, particularly white Georgians and white Americans more broadly, whose time is not similarly consumed with correcting the wrongs of disproportionate policing.

Guider lost her job over those three days.

“My job is not going to hire me back,” she said. The position allowed her to flex her hours around her school and church schedule, and she could carpool with coworkers in the morning. (Guider does not have a car.)

She also spent the last of her money bailing herself out.

“I promise you,” she said of her bail costs, “I had just enough money to buy me the little $2 box at Checker’s,” a nearby fast-food joint.

Guider’s mother, who learned of her daughter’s incarceration on the evening news, watched after Guider’s son until her return. But the days-long absence impacted Guider deeply.

“It was one thing for me to be in jail,” she said, “and another thing being away from my son. Every time I woke up without my son, I cried.”

Guider spoke with an acute awareness of the ways her motherhood would be used against her in the court of public opinion.

“Some people looked at the incident as, ‘You’re a mom, you shouldn’t have even been there,’” she said. “And then I’m looking at it as, ‘I shouldn’t be going through all this.’”

When all was said and done, Guider and the dozens of others implicated in alleged drug crime saw the charges dropped.

Many of us might want to dismiss Guider’s trauma as a mere peculiarity, or suggest that the sole responsibility rests with the backward state of Georgia.

But truly, these are national sins. The same racist impulses condemning this young woman in right-leaning Georgia have been found in left-leaning California.

Customers line up in West Hollywood as the legal sale of recreational marijuana begins in California. Photo: Christina House, Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

At 49 years old, Linda Grant is a prime example of the enduring costs incurred by people who end up in the justice system for weed. Having been jailed in 2003 for an ounce of weed, even she ― now a licensed cannabis salesperson ― feels a lingering air of persecution.

“Back then, I was told if I ever got caught with an ounce of weed that I was going to do 10 to 20 years in prison,” she said. “They told me I would never see my kids again. Now, to be able to have this permit, it’s still unreal. And it’s still scary.”

The same nation which harasses black mothers for standing in the same room as cannabis celebrates white mothers for inhaling it. And black women are bearing the psychological and financial burden.

Reckoning with cannabis use in America is not as simple as legalizing it; not when racial biases within us — deep as the marrow — inflect our every experience with it, in industry, incarceration and elsewhere.