By Frank Joyce / AlterNet

Ah, July 4th. Of all the national orgies of self-congratulation, militarism and, of course shopping, this one stands out. Even more than say Memorial Day it perfectly captures the combination of myths and ignorance that make up the fairy tale view we hold of our national origins and character.

Fortunately, a new generation of scholars is bringing new research and perspective to our understanding of what really happened and especially why white racism is so intractable. One reason is that its roots run so much deeper than most whites even begin to understand or acknowledge. (A partial list of essential recent books appears at the end of this article.)

What most of us think the Declaration of Independence says is this and only this:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

But there was much more to the Declaration than those famous words. Far more attention was dedicated to a long list of grievances that the founding fathers had with the King. One of them was that the British were in cahoots with, “the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages.” Another complaint which didn’t make it into the Declaration but was included in a precursor document, the Virginia Constitution, complained that the British were “prompting our Negroes to rise in arms against us…”

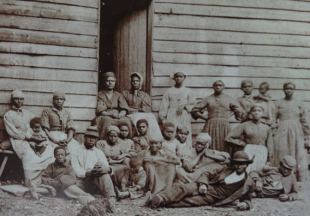

The first slaves arrived in what is now the United States in 1619. By the late 1700’s they were already a critical component of the economy and of the political conversation that led to the conflict with England.

So much so that historian Gerald Horne poses a radical reinterpretation of the founding of the nation’s origins, in his trailblazing book, The Counter-Revolution Of 1776. “Ironically, the founders of the republic have been hailed and lionized by left, right and center for—in effect—creating the first apartheid state,” he writes.

Citing previously ignored evidence, Horne argues convincingly that a combination of alarm over the growing abolition sentiment in Britain, well underway by the late 1700’s, and the deep rooted fear of potential British support for slave uprisings were major motivating forces behind the desire for “independence” in the first place.

And indeed, notwithstanding the legend of Crispus Attucks, a black man, as the first pro-independence casualty of the revolution, most African Americans and indigenous people who fought at all fought on the side of the British. And why not. Nothing was to be gained for them in transferring power from the King of England to the white property owners of the colonies, many of whom were slave-owners or otherwise profiting from the slave trade.

Thomas Jefferson himself said as much in his account of the Declaration of Independence, “The clause too, reprobating the enslaving the inhabitants of Africa, was struck out in complaisance to South Carolina and Georgia, who had never attempted to restrain the importation of slaves, and who on the contrary still wished to continue it. Our northern brethren also I believe felt a little tender under those censures; for tho’ their people have very few slaves themselves yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others.”

The Inconvenient Truth

The reality represented by July 4th is this: protecting slavery and antagonism toward Native Americans was inseparable from the lofty ideals promulgated by the founding fathers. Yes, the one percenters of 1776 sought “freedom” from a colonial master. But accurately understanding our history makes it clear that the “revolution” was not against colonialism per se. Rather it was to swap the masters at the top of the colonial pyramid from those who lived in England to those who lived in Virginia, Maryland, New York, South Carolina, Georgia and the rest of the 13 colonies.

For more proof, fast forward to the modern era. Is anti-colonialism at the core of our deepest values? When we celebrate July 4th, do we, for example, identify with other anti-colonial struggles such as that of the Vietnamese against the French following WWII? Of course not.

When Ho Chi Minh, who based the Vietnamese Declaration of Independence on our own, approached Harry Truman for assistance in throwing off the yoke of French colonialism, Truman famously turned a deaf ear. In fact the United States became a major supporter of the French to the point of offering them nuclear weapons to use against the Vietnamese. This despite the fact that the US was only too willing to fight side-by-side with Ho Chi Minh in WWII against the Japanese.

And as we all know, when the Vietnamese defeated the French and won their independence anyway, the US took up the fight to overthrow Ho Chi Minh directly, bringing enormous death and devastation to Viet Nam, Laos and Cambodia. The US record of support for anti-colonial struggles in Africa is no better.

With the possible exception of some interventions driven by geo-political considerations, the United States has never supported any anti-colonial struggle except our own. To be sure, along with solidifying the first apartheid state, the revolution also set the stage for the State protecting some core ideals such as trial-by-jury and freedom of movement, press and speech. That’s why this essay can be openly published.

That does not change however the fact that the fight for independence from England decidedly did not draw a principled line against colonialism. Rather, it was a fight for control of the settler colonialism that came to define the history of brutal westward expansion to California, Hawaii, the Philippines and beyond.

As Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, author of another ground breaking book, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States, points out in a recent article:

US policies and actions related to Indigenous peoples, though often termed “racist” or “discriminatory,” are rarely depicted as what they are: classic cases of imperialism and a particular form of colonialism—settler colonialism.

The extension of the United States from sea to shining sea was the intention and design of the country’s founders. “Free” land was the magnet that attracted European settlers. After the war for independence but preceding the writing of the US Constitution, the Continental Congress produced the Northwest Ordinance. This was the first law of the incipient republic, revealing the motive for those desiring independence. It was the blueprint for gobbling up the British-protected Indian Territory (“Ohio Country”) on the other side of the Appalachians and Alleghenies. Britain had made settlement there illegal with the Proclamation of 1763.

Especially taken together, the work of Horne, Dunbar-Ortiz, Ned and Constance Sublette and others demolishes the storybook picture that has dominated the telling of US American history for centuries. Perhaps most importantly their research reveals that US capitalism and the unique US slave system were invented simultaneously as one thing. This places debates over race versus class in a different perspective. Simply put, it’s a mostly useless conversation that does more to obscure what we are dealing with than to explain it. And yes, the left sadly has its own virulent strain of race deniers past and present.

Especially as cotton became the driver of the global economy, race-based capitalism drove the push for more territory for slavery in the South and West. That not only exponentially expanded the market for the domestic slave industry, it also contributed greatly to the need to slaughter and displace Native Americans. Mile by mile; law by law; massacre by massacre; whipping by whipping; lynching by lynching and war by war the system that drives the violent and existential danger to all life visited by white male power all over the earth was created and consolidated.

By The Dawn’s Early Light

O’er all this waves the flag. Nothing gets more attention on July 4th than the flag. Ironically, all by itself, the stars and stripes can tell us more than we learn from textbooks. The stripes of course are the original 13 colonies. The stars represent brutal colonial expansion and plunder of which Hawaii, the 50th state is an especially poignant example.

As a relevant side note, the National Anthem has its own dirty little secret. Composed during the fight with the British known as The War of 1812, its third stanza is virtually never sung today. As Ned and Constance Sublette explain in The American Slave Coast—A History of the Slave-Breeding Industry there is a reason for that. The last part of that stanza is:

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave,

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Frances Scott Key, author of the Star Spangled Banner lyrics, was himself a slave owner and hard core white supremacist. The reference to the hireling and the slave is to those, including former slaves, who were fighting on the side of the British. The Sublette’s point out further, “New England did not want the war of 1812, the Southerners did. They got what they wanted: under cover of war with Britain a substantial chunk of the Deep South was made safe for plantation slavery when Andrew Jackson vanquished the Creek Nation and took its land.”

Do we have a better banner to wave? Not yet.

So, does this mean that there is nothing to celebrate in the founding of the United States? That is a good and difficult question. Frederick Douglass wrestled with it when asked to speak to a gathering in Rochester, New York on July 4th, 1852:

Fellow Citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of this republic. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were brave men. They were great men, too — great enough to give frame to a great age. It does not often happen to a nation to raise, at one time, such a number of truly great men. The point from which I am compelled to view them is not, certainly, the most favorable; and yet I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration. They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory.

Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here today? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? and am I, therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and to confess the benefits and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting from your independence to us?

Would to God, both for your sakes and ours, that an affirmative answer could be truthfully returned to these questions! Then would my task be light, and my burden easy and delightful. For who is there so cold, that a nation’s sympathy could not warm him? Who so obdurate and dead to the claims of gratitude, that would not thankfully acknowledge such priceless benefits? Who so stolid and selfish, that would not give his voice to swell the hallelujahs of a nation’s jubilee, when the chains of servitude had been torn from his limbs? I am not that man. In a case like that, the dumb might eloquently speak, and the “lame man leap as an hart.”

But such is not the state of the case. I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. — The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me.

The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak today?

That was 164 years ago. Who do we mock today if we wallow in July 4th business as usual? It was one thing for Frederick Douglass to begin his remarks by offering respect to the Founding Fathers in 1852. In 2016 race based capitalism menaces not just enslaved Black people and Native Americans, but animals (including humans), plants, oceans, lakes and air. Changes in form such as the hard-won expansion of the franchise notwithstanding, white male power rules the earth more dangerously today than it did in 1776.

So as we peer through the haze of fireworks, barbeque smoke and the red glare of drone fired rockets this July 4th, let us spend some time in contemplation. If indeed we are “free,” does our freedom permit us to move past the triple evils of racism, materialism and militarism that Martin Luther King challenged us to confront?

The late Vincent Harding dedicated his life to the belief that we can. Vincent was fond of saying, “I am a citizen of a country that does not yet exist.” Amen to that.

(An incomplete but basic list of essential new work on US history includes, Gerald Horne’s The Counter Revolution of 1776 (and several other works covering the same era); The American Slave Coast—A History of the Slave-Breeding Industry by Ned and Constance Sublette; The Half Has Not Been Told by Edward Baptist; An Indigenous People’s History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz; Empire of Cotton—A Global History by Sven Beckert and Slave Patrols—Law And Violence In Virginia And The Carolina’s, by Sally E Hadden.