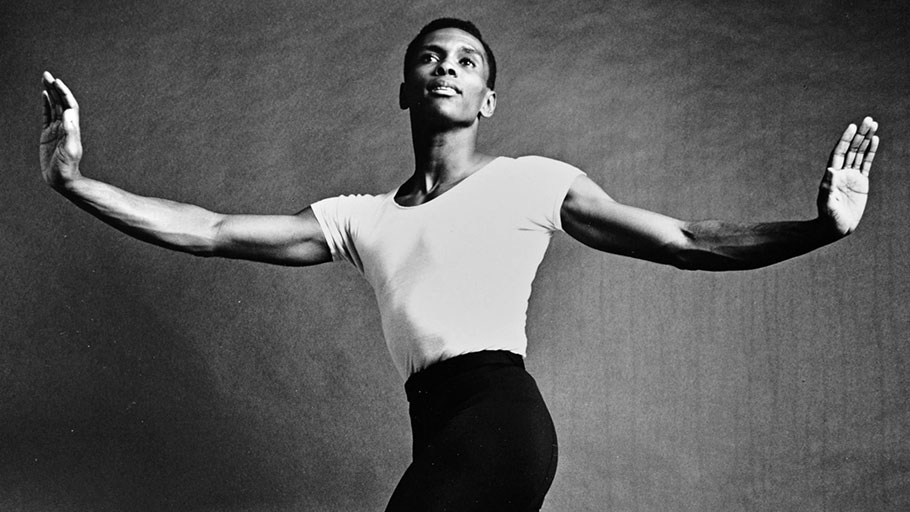

Arthur Mitchell dancing with New York City Ballet, 1963. Photograph: Jack Mitchell/Getty Images

The first African American principal dancer to star in a major ballet company.

By Wendy Perron, The Guardian —

A star of New York City Ballet and the co-founder of Dance Theatre of Harlem, Arthur Mitchell was also the first African American principal dancer in any major ballet company. Mitchell, who has died aged 84, had classical lines, buoyant energy and a palpable joy in movement.

In NYCB, where he danced from 1955 to 1968, he gained renown for two roles he created: the startlingly modernist Agon pas de deux, choreographed for him and Diana Adams by George Balanchine, and the mischievously bounding Puck in Balanchine’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. According to his fellow NYCB dancer Jacques d’Amboise, “every time we toured Europe, he was a sensation … There would be hundreds of fans at the stage door.”

After Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968, Mitchell had his own dream, which was to form a top-notch ballet company that would shatter the myth that black bodies were not “right” for ballet. In a garage lent by the Harlem School of the Arts and with the support of his mentor Karel Shook (artistic director of Dutch National Ballet), he started a school. They left the doors open to attract young people from the street. To keep them there, Mitchell compared ballet to basketball, hired drummers instead of pianists to accompany the class, and allowed the boys to wear jeans. Within four months, Dance Theatre of Harlem school had 800 students, and the professional company debuted in 1971 at the Guggenheim Museum. It thrived for more than three decades, becoming one of the most sought-after dance companies in the world.

Arthur was born in Harlem. His father, Arthur Mitchell Sr, was a janitor, and his mother, Willie Mae (nee Hearns), raised their five children. From the age of 12, Arthur helped support his family by shining shoes and delivering newspapers. He started singing at the local Police Athletic League, a youth programme run by US police departments, and tap dancing in neighbourhood studios. A guidance counsellor spotted him dancing at a junior high school party and suggested he audition for the High School of Performing Arts (now the Fiorello LaGuardia High School).

After graduating from LaGuardia in 1952, he won a scholarship to the School of American Ballet, the training ground for Balanchine’s New York City Ballet. He danced with John Butler Dance Theater and with the modern choreographers Sophie Maslow, Anna Sokolow and Donald McKayle before joining NYCB. While still in the corps, he stepped in for d’Amboise in Balanchine’s Western Symphony. As Puck, he brightened the entire stage with his devious bounding. For Agon, he had no problem with Stravinsky’s atonal music. “Because I can tap dance, I can always find the pulse,” he said.

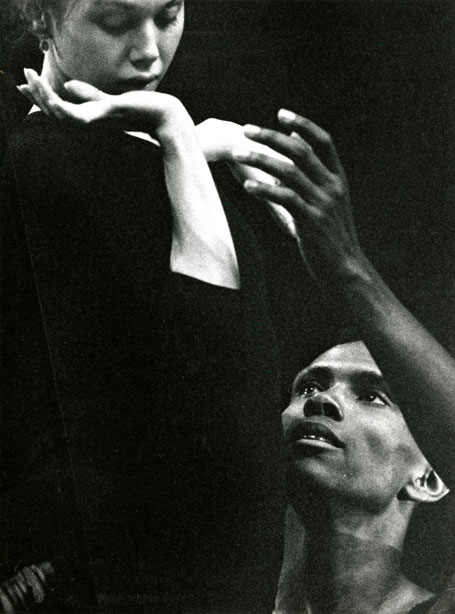

Mitchell praised Balanchine for having an African American man dance with white ballerinas in the time of civil rights. He was very aware of the potential controversy of the central pas de deux in Agon. The man manipulates the woman in ways that bring their bodies into unusual points of contact. “He used our skin tones as part of the choreography,” Mitchell said. “Like where I have my arm, or how I would take her foot.” However angular the choreography, Mitchell, who was promoted to soloist in 1958 and principal in 1962, always presented his ballerina graciously.

Arthur Mitchell as artistic director of Dance Theatre of Harlem, with dancers after a class in 2003. Photograph: Washington Post/Getty Images

The ballerina Allegra Kent, who partnered Mitchell in Agon during an NYCB tour of the Soviet Union in 1962, recalled how “the audience went wild” during their performance. She said: “Arthur was a superb partner. His musicality and stagecraft enhanced the choreography and made his partner look great.”

As co-founder and artistic director of DTH, Mitchell did not perform on stage, but his infectious energy made his mission come alive for those around him. One of his innovations was to replace pink tights and pointe shoes with those dyed to match each dancer’s skin colour, aligning the aesthetic with the Black Is Beautiful movement.

Balanchine supported the enterprise by giving his ballets gratis, including Agon, Concerto Barocco, Prodigal Son and Bugaku. However it was Geoffrey Holder’s Dougla (1974) that brought the house down. With its festive costumes, extreme technique and Trinidadian blend of African and Hindu traditions, Dougla concluded each programme with a gloriously giddy celebration. When the company debuted at Sadler’s Wells, London, in 1974, Mary Clarke wrote in the Guardian: “The company is irresistible. Young, fresh, still excited about the pleasures of the physical movement, they move with ease from the most demanding choreography of George Balanchine to the classical capers of Le Corsaire.”

Allegra Kent and Arthur Mitchell rehearsing Agon. Photograph: Fritz Peyer/Arthur Mitchell Collection, Rare Book & Manuscript Library/Columbia University

In addition to Holder, Mitchell commissioned ballets by John Butler, John Taras and Talley Beatty, and choreographed a few of his own. He also mounted an evening of works by Nijinska.

Sir Frederic Franklin, of Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo fame, staged Swan Lake and Valerie Bettis’s A Streetcar Named Desire for DTH. But it was his Creole Giselle that established the group’s ability to weave magic into a full-length romantic ballet. Mitchell set the ballet in the Louisiana bayou, and Franklin, who later became artistic adviser of DTH, staged it with traditional steps, but changed the harvest from grapes to sugar cane. When it premiered at the London Coliseum in 1984, Creole Giselle received the Olivier award for the most outstanding dance production of the year. It was broadcast on US public television in 1987.

In 1992 DTH was invited to perform in South Africa. Mitchell was reluctant, but Nelson Mandela called him and persuaded him that the young people needed inspiration. The company made the trip and performed for newly integrated audiences. Mitchell’s experiences teaching children in the townships inspired him to start the Dancing Through Barriers outreach programme at DTH.

Plagued by financial difficulties in 2004, DTH took a break. Mitchell named Virginia Johnson artistic director in 2009 but the company did not resume full operation until 2012. It celebrates its 50th anniversary this season.

Mitchell’s awards include a National Medal of Arts, a Kennedy Center Honor, and a MacArthur “genius award”. Earlier this year, Arthur Mitchell: Harlem’s Ballet Trailblazer, a show celebrating his life and work, was held at the Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University.

He is survived by a niece.

Arthur Adam Mitchell, dancer, choreographer and artistic director, born 27 March 1934; died 19 September 2018