The late James Forman, in his book The Making of Black Revolutionaries, signaled the arrival of Bob Moses to the civil rights movement. “A New York school teacher, Moses had quit his job and begun to work full time in Mississippi voter registration. He did not attend the workshop [preparing volunteers] but his ideas would soon feed into the mainstream of Southern students thinking about what forms of action to take.”

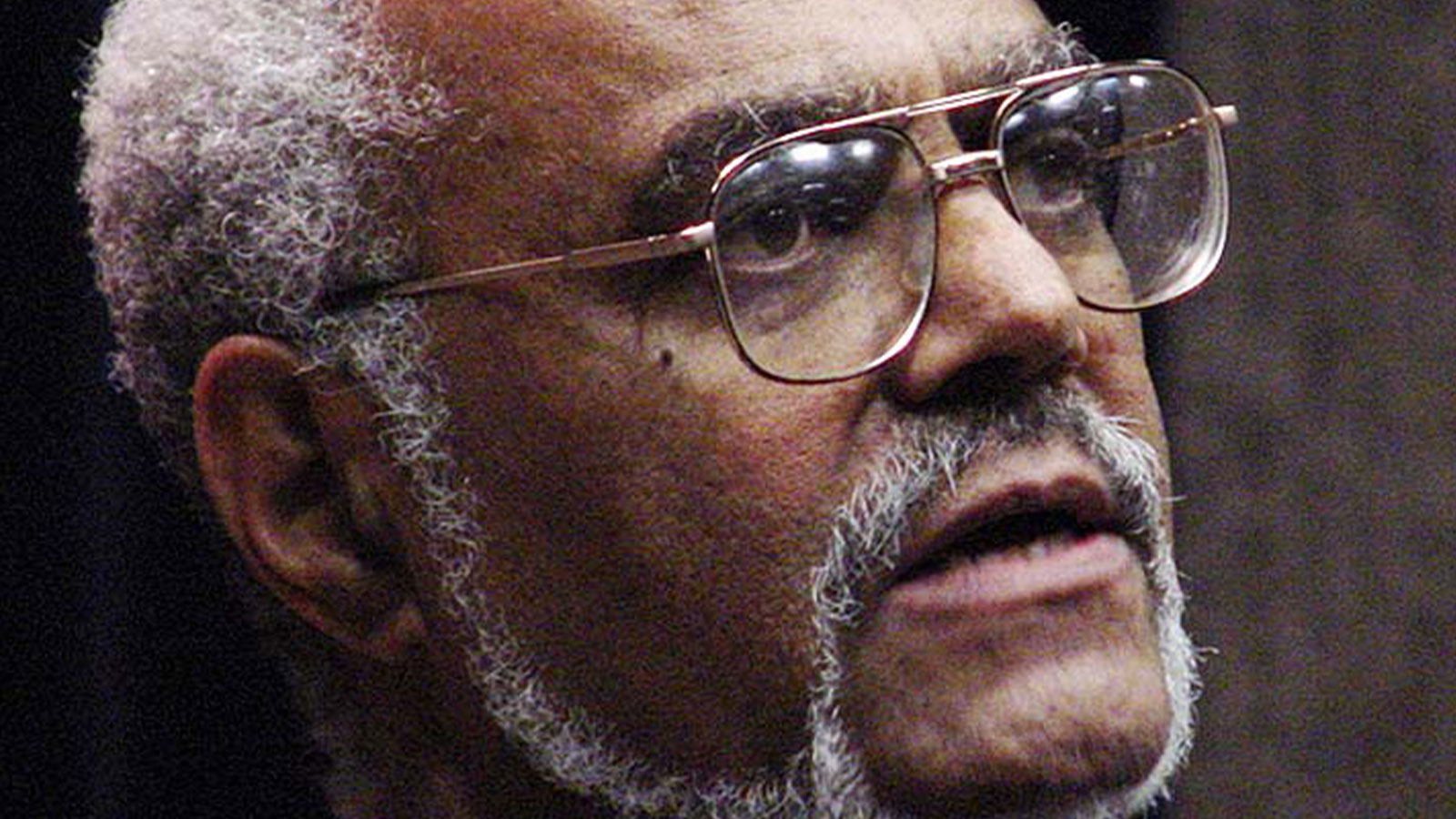

Forman, who was executive secretary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, from 1961-1966, not only chronicled Moses’ arrival in the summer of 1961, he witnessed his courageous, relentless commitment to overturn the racism of Jim Crow. Moses was in McComb, Mississippi but a few days before he was savagely beaten for leading a group of Black citizens to register to vote. This moment epitomized this legendary civil rights activist who died July 25 at his home in Hollywood, Florida. He was 86 and no cause of death was specified.

Beaten, shot at, arrested and jailed, none of these acts of terrorism stopped Moses in his fight for equal rights and against the tyranny that kept countless number of Black Americans for exercising their democratic rights. In his book Radical Equations—Math Literacy and Civil Rights, co-authored with Charles Cobb, Jr., Moses relates that “The sit-ins woke me up. Until then, my Black life was conflicted. I was a twenty-six-year old teacher at Horace Mann, an elite private school in the Bronx, moving back and forth between the sharply contrasting worlds of Hamilton College, Harvard University, Horace Mann and Harlem.”

Mississippi may have been another eye-opener, but he was born Robert Parris Moses in Harlem on January 23, 1935. He graduated from the elite Stuyvesant High School in 1952 and four years later received his B.A. from Hamilton College. After earning his Master’s degree in philosophy from Harvard University, he began teaching at Horace Mann High School.

Before eventually following his impulse to join the civil rights movement he had ventured to Mississippi, but the young people participating in the sit-ins sealed the commitment. Rather than adhering completely to Dr. King’s style and tactics, Moses improvised on those put forth by Ella Baker, “quiet work in out-of-the-way places” and getting to the “radical” root causes of the problem. Such a strategy, however, did not make him immune to the brutal reception he received from the arch-segregationists. And even in those remote locations, he was highly visible in his role as director of SNCC’s Mississippi Project, and traveling from county to county.

His fearless leadership was soon widely recognized and in 1964 he became co-director of the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) and consequently a key organizer of the Freedom Summer project to educate and register Blacks to vote. The initiative received public notice when three of its volunteers—James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman—whose bodies were found in a buried earthen dam. It was a terrifying incident and it was all Moses could do to calm the other volunteers and keep them from departing.

When Fannie Lou Hamer and her cohort formed the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, Moses was a vital ally but he was disheartened by the results and this along with other setbacks led to his resignation of COFO and even the U.S. settling in the East African nation of Tanzania. In 1976 he returned to the states and began graduate work at Harvard in the philosophy of mathematics while teaching high school in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

He was the recipient of MacArthur “Genius” Scholarship in 1982 and used the award to create the Algebra Project, mainly to improve the math skills of Black Americans and other minority groups. The project received an award from the National Science Foundation in 2006 to expand on his innovative approach to the teaching of algebra that he viewed as an aperture to a wider understanding of science, technology, and other facets of our culture.

In 2006, he was named Frank H.T. Rhodes Class of ’56 Professor at Cornell University. With the publication of his book Radical Equations in 2001 and his academic standing lecture circuit expanded exponentially as well as the honorary degrees.

The civil rights icon and mathematician is survived by his wife, Janet Moses, his daughters Maisha and Malaika; his sons Omowale and Tabasuri, and seven grandchildren.