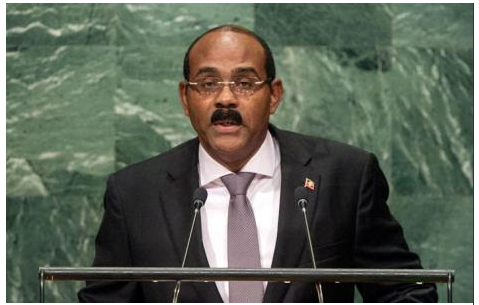

NEW YORK, USA — Gaston Browne, prime minister of Antigua and Barbuda, told the United Nations General Assembly on Saturday that, along with climate change and lingering indebtedness, Caribbean islands face another existential threat from the withdrawal by global banks of correspondent banking relations to their financial institutions.

In the global campaign against money-laundering and terrorist financing, very strict penalties have been imposed on banks by regulatory bodies in North America and Europe for any infringement of the stringent regulations.

“In this environment, where even the slightest infraction could expose a bank to a fine of hundreds of millions of dollars, many have chosen to withdraw essential correspondent banking relations from financial institutions in the Caribbean, Central America and Africa,” he explained, adding: “They call this process de-risking. I call it economic destruction.”

Browne said while this trend is prevalent in a few regions, it will spread with global consequences unless checked by collective action.

“We would be severed form the world’s trading system, unable to pay for basic services we purchase, or to receive payments for gods and services we sell to other countries,” he explained, stressing that this “growing cancer” would likely lead to economic collapse, poverty and high crime in small countries and worse still, would force underground the financial transactions that are being regulated by law enforcement agencies, creating huge opportunities for money laundering and terrorist financing.

“This would undermine the very global, multilateral cooperation that is required to fight these scourges,” he said, and noted that of all the terrorist financing and money laundering cases that have been prosecuted, not a single one of them involved Caribbean financial institutions.

Given their size and limited choices for economic expansion, small island states like Saint Lucia have looked to the more advanced economies for innovative means of economic development, the country’s prime minister, Allen Chastanet, also told the United Nations on Saturday, among many speakers from the region who said they now find themselves being penalized as tax havens by the very architects of such strategies.

Having adopted programmes created by wealthy countries, such as citizenship by investment’ programmes, and financial services and trusts, small island states have been “left to dance between the raindrops, criticized by the very same countries and branded as tax havens.

“A painful example of such exclusion is the inescapable fact that while we continue to feel the negative effects of the 2008-2009 global financial and economic crises, we are not involved in the solutions to the problems,” he said, noting that while the G20 has designated itself the forum for collective international economic cooperation, Saint Lucia, like the majority of UN member states, is not a member of that bloc, “nor were we consulted on its appointment as the arbiters of our economic fate.”

The G20 also has a serious legitimacy problem, Chastanet continued, noting that aside from being unofficial and non-inclusive, many of the countries at the table represent the champions of the economic and financial systems and policies that led the world into the crisis in the first place.

“The crisis has produced in our states, increased poverty, suffering and social and political upheaval. Its disproportionate impact on the poor has only widened the gap between developing and developed countries,” he said.

For his part, Dr Timothy Harris, prime minister of St Kitts and Nevis, said the trend has led to Caribbean and other small island states being further marginalized in the global financial system. Already, in the Caribbean, as of the first half of this year, some 16 banks across five countries have lost all or some of their correspondent banking relationships, putting the financial lifeline of these countries at great risk.

“In our tourism-dependent economies, where remittances factor greatly in national development, such actions threaten to derail progress, undermine trade, direct foreign investment and repatriation of business profits,” he explained, also echoing the region’s call on the G7, G20 and the international financial institutions to reevaluate the methodologies used to assess how and whether a country qualifies for concessional support or access to certain types of international funds.

As the world sharpened its focus on achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), it must recognize the stakes for small island developing states, Francine Baron, the minister for foreign affairs of Dominica told the United Nations on Saturday, noting that the 2030 Agenda must drive action on climate change, environmental protection and access to clean energy, all critical concerns for Caribbean countries.

“Realizing the Sustainable Development Goals is not about ticking boxes, but about making a real difference, said Baron, who stressed that the effects of climate change continue to impact development in her region, as countries are experiencing more severe and prolonged droughts, often times followed by sudden and high volumes of rainfall which result in massive soil erosion and catastrophic loss and damage.

“Likewise, the ongoing phenomenon of beach erosion, destruction of coral reefs – so vital to our tourism product and the character of our islands – risk untold damage, to our prized tourism assets,” she said, calling for more urgent and wide-ranging action “to ensure our very survival.”

In this regard, she looked forward to building on the momentum generated by the Paris Agreement ahead of the next meeting of the States Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), in Marrakesh next year.

As an example of the urgency of the issue, Baron noted that Dominica had been painfully reminded of that in 2015, when Tropical Storm Erika had killed 30 of its citizens. That event had caused economic damage estimated at $483 million, the equivalent of 90 percent of national gross domestic product (GDP), she recalled.

While Dominica has since made great strides in building more climate-resilient and adaptive infrastructure in a process facilitated by the support of bilateral and multilateral partners, it “still suffers the disproportionate burdens and impacts of climate change,” which hamper its efforts to develop in a sustainable manner, she said, adding that resources intended for sustainable development programmes have instead been shifted to post-disaster rehabilitation efforts.

Dominica, therefore, continued to call for the establishment of an international natural disaster risk fund, she said, describing the Caribbean Risk Fund and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank Disaster Recovery Facilities as “good starting points.”

In her address, Maxine McClean, minister for foreign affairs and foreign trade of Barbados, said it is necessary to act now to make the vision of the 2030 Agenda a reality, and that this is particularly true for the small island developing states. She was proud to have participated in the launch, in Barbados, of the Caribbean Human Development Report 2016, and noted the three central issues it highlighted for low-lying coastal Caribbean states: vulnerability, resilience and sustainability.

The existential threat which climate changed posed for island states is well-documented. The prime minister of Barbados had participated in the signing ceremony of the Paris Agreement at the UN in April, and deposited the instrument of ratification on the same occasion. Barbados developed a national climate change policy framework, and recognized the potential of sustainable ocean exploitation as an important component of its future development.

“As we seek to protect and preserve our oceans and seas for future generations, Barbados will continue to participate actively in the various oceans-related processes of the United Nations,: reported McClean, noting that during this current session, her delegation will collaborate with other members of the Association of Caribbean States to strengthen the level of support for the ‘Caribbean Sea Resolution,” with the ultimate aims of designating the Sea as a “special area in the context of sustainable development.”

In his remarks, Elvin Nimrod, minister for foreign affairs of Grenada, said history has shown that development is tenuous wherever human rights and the environment are not prioritized. The 17 SDGs are the product of “deep reflection and learning, and the realization that development without human rights and environmental considerations is unreliable.”

With this in mind, he said Grenada is resolute in its commitment to conserve and promote the sustainable use of the oceans, seas and marine resources, in line with SDG 14. Indeed, the ocean economy is an important starting point for thinking about conservation.

“The natural capital of the ocean is like the principal deposit of an interest-bearing bank account. Unfortunately, instead of living off the interest, we have been drawing from the principal,” he said.

Nimrod said the work done by the World Wildlife Fund and the Boston Consulting Group on the Ocean Economy notes a $24 trillion asset value of the oceans, which generates $2.5 trillion per year. “The need to preserve this natural capital is self-evident,” he said, adding that nine Caribbean nations have committed to conserving and managing 20 of the region’s marine and coastal environment by 2020.

On Friday, two Caribbean island nations took to the podium at the United Nations General Assembly to highlight their vulnerabilities, including indebtedness and poor access to financing for development.

“Like many other countries, our path towards sustainable development has been hindered by years of low growth, crippling national debt and high unemployment, which have been exacerbated by our vulnerability to natural hazards and other exogenous shocks,” Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness told the Assembly’s annual debate.

Highly indebted middle income countries (HIMIC) like Jamaica are poised for economic transition with relatively high levels of health and education attainment, he said. However, in a climate of historically low economic growth, this potential is gravely threatened, ironically, by having to choose between debt repayment and catalytic growth spending, he added.

“For Jamaica, there is no choice. Jamaica must, and we are, repaying our debt,” he said.

The consequence of this is that there are no resources available for the government to make the kinds of public investments that can stimulate economic activity. In addition, spending on critical issues such as security, the absence of which negatively impacts growth, is compromised.

In these circumstances, developing countries would ordinarily be able to tap into development assistance that can be used for growth inducing countercyclical investment in infrastructure, which in turn strengthens debt repayment capacity, he said. However, arbitrary classification on the basis of gross domestic gross domestic product (GDP) per capita precludes HIMIC from accessing such resources.

Reforms do not immediately kick-start the growth cycle. Instead, new investment needs to follow, of a scale and velocity that is difficult to undertake without the full engagement of international development institutions, he said.

This creates the prospect for the so-called “HIMIC trap,” a situation where countries are at the cusp of transitioning but are stalled with a risk of reversal, Holness explained.

He stressed the need to review this broad categorization of countries as this per capita GDP measure in isolation fails to fully and accurately capture added vulnerabilities, and levels of indebtedness.

He also spotlighted the need to effectively address the emerging crisis of the withdrawal of correspondent banking services to certain financial institutions in the Caribbean.

“De-risking threatens our economies. This trend hinders our participation in the global financial system and in international trade,” he said, noting that trade represents about 70 per cent of the Jamaican economy and, as such, de-risking measures threaten its integration and economic viability.

He encouraged international partners to establish principles that ensure inclusive development strategies based on a country’s ability to engage in a vibrant, dynamic international trading system.

Also addressing the annual debate on Friday was Dr Ralph Gonsalves, prime minister of St Vincent and the Grenadines, who said that a number of rules and regulations implemented in the wake of the 2008 crisis and the global war on terror have had unintended, and potentially devastating impacts on the economies of small states.

Current heavy-handed Financial Action Task Force (FATF) regulations have led to a wave of de-risking and loss of correspondent banking relations in the Caribbean banking sector.

“These regulations must be revised urgently before legitimate transactions in the Caribbean – from credit card payments to remittances to foreign direct investment – grind to a halt,” he said.

In its quest for affordable and clean energy, St Vincent and the Grenadines has invested heavily in developing its geothermal resources, he said. By 2019, 50 percent of its national energy needs is expected to be supplied by geothermal energy and a full 80 percent of its energy will be generated by a mix of renewable resources, including hydro and solar.

The project is financed by partners, including the Clinton Global Initiative, the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development, the Caribbean Development Bank, and the International Renewable Energy Agency.