By Christopher Mathias National Reporter, The Huffington Post

Preston Gilstrap, 64, was a Dallas police officer for over 41 years before he retired in 2013. Earlier this week, he saw the two brutal videos of police officers killing black men ― Philando Castile in St. Paul, Minnesota, and Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana ― that shook the nation.

And Friday morning, Gilstrap, who is black, woke up to news of the horror that had visited his hometown: at a peaceful Black Lives Matter protest Thursday night over the killing of Castile and Sterling, a lone gunman opened fire, killing five Dallas police officers and wounding nine other people.

“My heart has been totally torn out of my chest by both violence perpetrated on officers and violence perpetrated by officers,” Gilstrap told The Huffington Post Friday.

“These officers were there to protect the protesters and make sure their expression of discontent and freedom of speech were protected,” added Gilstrap, who has long advocated for police reform. “They were taking selfies [with the protesters.] There was nothing wrong with the protest.”

Malik Aziz, an active-duty deputy chief in the Dallas Police Department and the national chairman of the National Black Police Association ― which also advocates for police reform ― said Friday that “the atmosphere is somber” in the police department right now. “And one of disbelief.”

Dallas Deputy Chief Malik Aziz, who is also the chairman of the National Black Police Association.

“Our hearts are very heavy,” he said. “The citizens here have shown so much love and support.”

“In 27 years of law enforcement my heart has never been this heavy and I have never felt this way,” he said. “This is the worst day in our history and among the worst in our nation’s history of policing.”

“I tell officers to take your time. Officers are human beings. We are hurting. We need healing. But we are professionals. We are now saying, ‘we are going to make it.’”

Corey Pegues, a former deputy inspector in the New York Police Department and author of the book Once a Cop: The Street, The Law, Two Worlds, One Man, said, “Every black cop in America was looking at their TV this week and watching the execution of Castile and Sterling and they were feeling really bad about being a cop because that’s not what being a cop is. These weren’t mistakes. These were executions.”

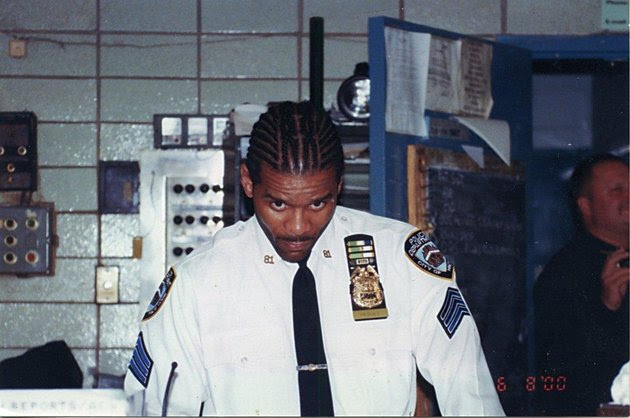

Corey Pegues, a former NYPD officer, shows off his corn rows after being promoted to lieutenant.

In the meantime, he added, black police officers “have family members getting stopped and frisked and wrongfully locked up, and then wake up in the morning and see that 10 cops are shot.”

Some politicians and pundits were quick on Friday to paint the triple tragedies of Minneapolis, Baton Rouge and Dallas as a kind of tit-for-tat battle between law enforcement and the police reform movement. The New York Post’s front page screamed “CIVIL WAR” and Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick (R) blamed Black Lives Matter protesters for the shooting.

But the experience of black police officers exposes such narratives as absurd. After all, black police officers naturally want black civilians to be policed fairly and without brutality, and they also want to ensure that their fellow officers ― their friends and colleagues ― aren’t killed in the line of duty.

“There is way too much blame to go around,” said Aziz, the Dallas police department deputy chief. “After the finger-pointing we need to sit together and commit to open dialogue for progression. We cannot operate on the false foundation of us versus them. This is all about us.”

Before the Dallas shootings, a black police officer in Ohio, Nakia Jones, gave an emotional speech on Facebook live that has since been watched over 7 million times. Jones, who works in Warrensville Heights, near Cleveland, had watched the video of Castile being shot during a traffic stop in St. Paul and was deeply disturbed by it.

She said that for the first time, she was able to see a police brutality incident through the eyes of a civilian.

“So I’m looking at [the video], and it tore me up because I got to see what you all see,” she said. “If I wasn’t a police officer and I wasn’t on the inside, I would be saying, ‘Look at this racist stuff. Look at this.’ And it hurt me.”

“If you are white and you’re working in a black community and you are racist, you need to be ashamed of yourself,” she added, her voice rising. “You stood up there and took an oath. If this is not where you want to work, then you need to take your behind somewhere else.”

But Jones said she still wants to be a cop. “I am my brothers’ and my sisters’ keeper,” she said. “That’s why I’m going to keep this uniform on.

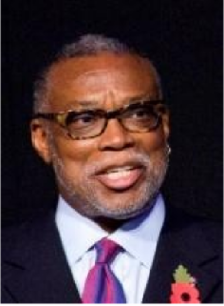

Ronald Hampton, a former Washington D.C. police officer.

Ronald Hampton was a police officer in Washington, D.C., for 24 years, many of those during the crack epidemic of the 1980s. He’s now retired and works with the Black Law Enforcement Association. He said he knows what it feels like both to experience systemic racism and to lose a fellow officer.

“When a white colleague was shot and killed, then of course I felt sympathy for him and his family,” he said. “But him getting killed didn’t erase the racism and discrimination I was experiencing in the police department. It didn’t erase [how police treated black communities]. Those are two separate things. One doesn’t eliminate the other. You have to deal with it.”

A cop car in Dallas is covered in flowers and messages of love Saturday, July 9, 2016.

What happened in Dallas, he said, is the result of decades of failing to hold cops accountable for acts of brutality.

“People who kill police officers go to jail,” he said. “Police officers who kill people don’t go to jail.”

“We’ve been talking about reform all the way back to the ‘80s,” he continued. “We saw these killings and Rodney King. We’ve been talking about reform and it hasn’t worked. There wouldn’t be Alton or Castile. There would be no Trayvon. It’s a lack of reform that has created the environment for police to keep doing what they do, without accountability.”

According to Damon Jones, a black corrections officer in Westchester County, New York, who also works for the Black Law Enforcement Association, police commissioners and politicians only “pay lip service” to comprehensive police reform. Meanwhile, “all these black men are still getting shot in 2016.”

Black law enforcement is caught in the middle. Damon Jones, corrections officer

“People have lost faith,” he said. “Then you have shootings of police officers and the first thing they do is point the finger at people voicing their opinion on the justice system and how black men are getting treated. And then you have crazies, with their own agenda, that use this conflict for their own agenda, not to bring law enforcement and the community together, but for their own sick reasons.”

“Black law enforcement is caught in the middle,” he added. “We understand the issues in black communities and the dangers that law enforcement face. It’s up to black law enforcement to fix this and be more vocal on this issue.”

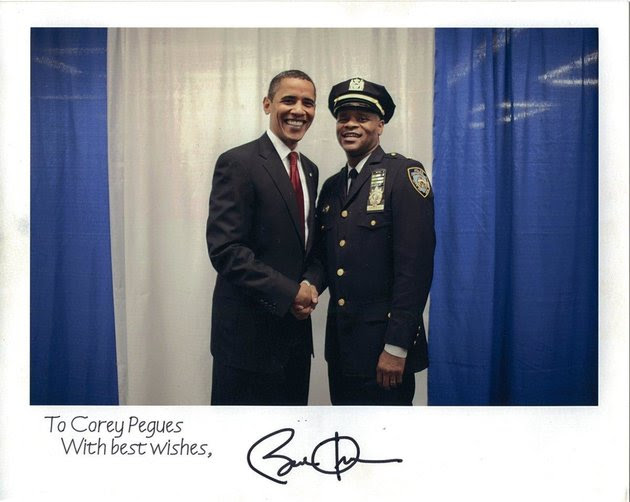

Corey Pegues poses with President Barack Obama.

Pegues, the former NYPD officer, agrees. He said “black cops are standing on eggshells right now. They want to speak out but they’re afraid to speak out for fear of backlash.”

“My advice is to black cops is specific: it’s to collectively come out and speak about the various injustices in their departments,” he said.

If they don’t put pressure on their police departments to make reforms, Pegues fears the U.S. will be doomed to a vicious cycle: police kill black people, leading to outrage and large protests, which in turn leads to deranged, lone wolf shooters who will start “plucking off cops.”

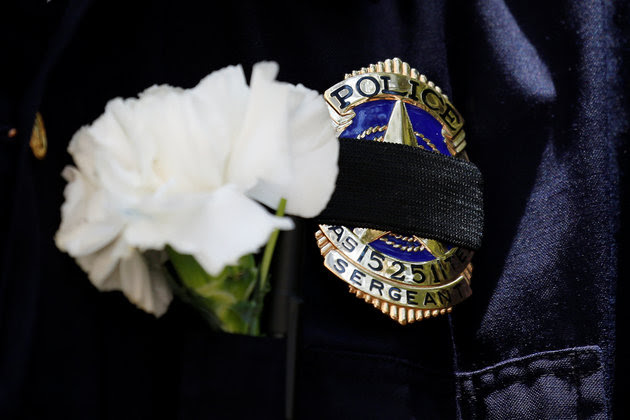

Police officers gather for the funeral of NYPD Officer Wenjian Liu. Liu and his partner, Rafael Ramos, were gunned down by Ismaaiyl Brinsley in December 2014.

He pointed to Ismaaiyl Brinsley, the man who killed two NYPD officers in Brooklyn in 2014 before taking his own life. Brinsley had posted to Instagram before the shooting that he planned to put “wings on pigs.” He added the hashtags #EricGarner and #MichaelBrown, both unarmed black men who died at the hands of police months before and whose deaths sparked massive protests across the country.

Similarly, the Dallas shooter, a 25-year-old Army veteran named Micah Xavier Johnson, reportedly said that he wanted to kill white people, and in particular, white police officers. Johnson was killed by police after a long standoff.

“We’re at a critical point right now,” Pegues said. “Action needs to be done. The various police officers need to discipline these rogue officers.”

“We can’t keep having this.”

Outside the Dallas Police Department on Saturday, Det. Ira Carter held a rose he received from a supporter. Nearby, two cop cars were smothered with flowers and signs of support.

“It’s tough to deal with, especially when you’ve lost officers you work with,” Carter said of the past couple days. “Looking out and seeing all the people who have come out to offer their support, it means a lot to us.”

Carter, who is black, said he respected the anti-police sentiments shared by some protesters — the same protesters his fellow officers lost their lives protecting.

“As police, we took an oath,” Carter said. “No matter who the person is, we took an oath to treat everybody equally.”

“We’re taking strides to try and do what’s right,” he added. “It’s not perfect, but we’re taking strides.”