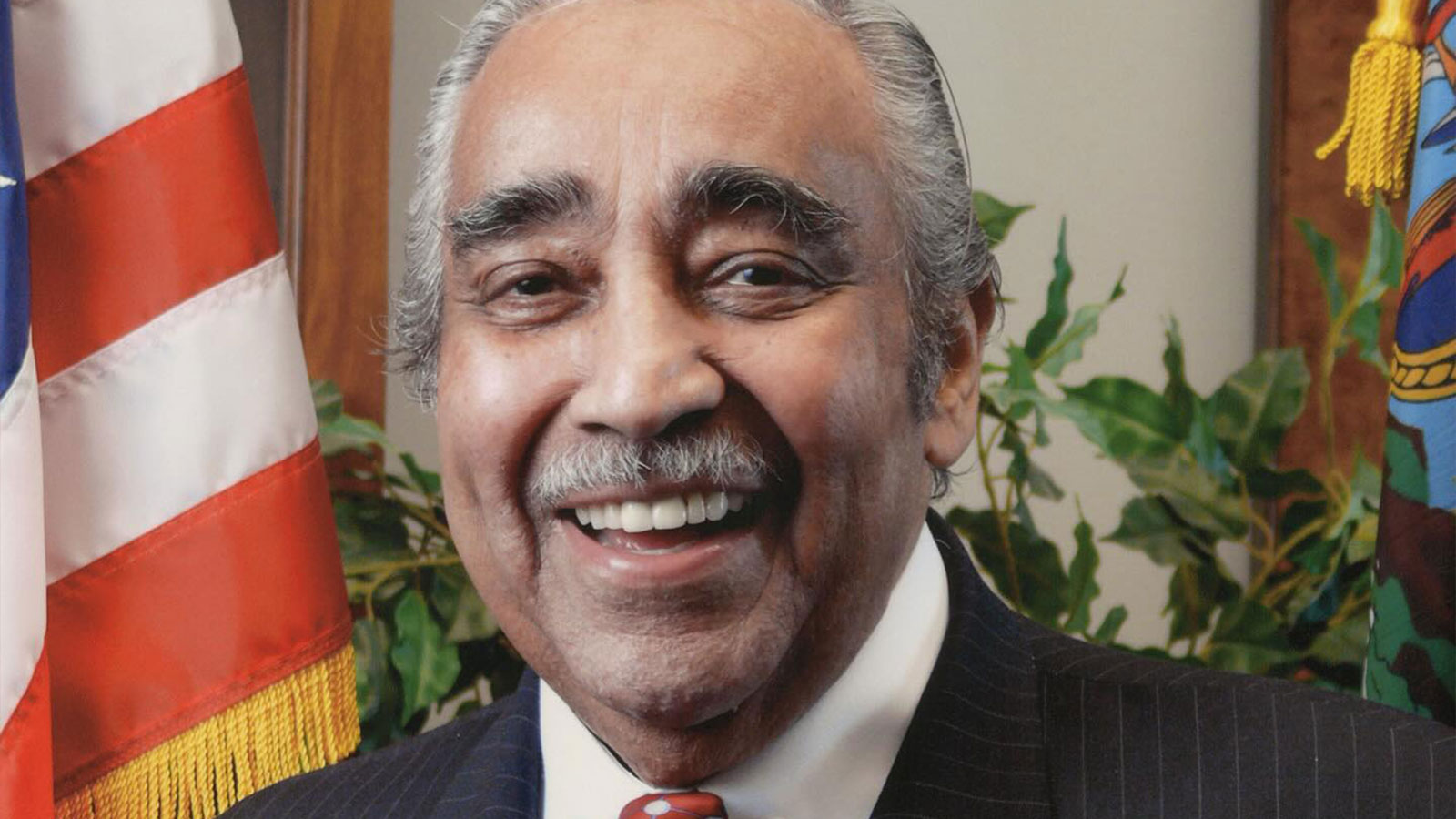

Charles Bernard Rangel, the former congressman from Harlem, and the last remaining founder of the Congressional Black Caucus, has died at age 94.

Charles Bernard Rangel, the former congressman from Harlem, and the last remaining founder of the Congressional Black Caucus, has died at age 94. Rangel passed away on Monday, May 26, Memorial Day, surrounded by family. He was a native of Harlem, and the lone surviving member of the legendary Gang of Four. He took his reputation as the “Lion of Lenox Avenue” to the House of Representatives in 1971 after defeating the renowned Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. The apogee of his tenure in Congress was in 2007 when he became chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee.

“Throughout his career, Congressman Rangel fought tirelessly for affordable housing, urban revitalization, fair tax policies, and equal opportunities for all Americans,” his family said in a statement.

In his autobiography, Rangel claimed he never had a bad day since he survived an attack by the Chinese and the North Korean armies when he served in the Korean War, “but it doesn’t mean I haven’t had some heartbreaking experiences,” he wrote, particularly noting the loss of his brother. “Setbacks I’ve had; but bad days, no.”

“Charlie was a transformative leader, he used his political position to elevate the people he represented. He was accessible and always available to anyone who came to him for assistance. He demonstrated that political figures could be honorable and serve as great examples for young people to follow. From Harlem, he made his mark on the country. He will always be remembered as a warrior for justice and equality,” said former NYS State Comptroller H. Carl McCall in a statement to the AmNews.

“It is sadly appropriate that my close friend and mentor ‘The Lion Of Lenox Avenue’ the great Charles B. Rangel would transition on Memorial Day,” said Lloyd Williams, President and CEO of the Greater Harlem Chamber of Commerce (GHCC). “Rangel was a true American hero, having been awarded the prestigious Purple Heart when fighting for our country during the Korean War in the 1950’s. Rangel will definitely go down in history as one of the most important and effective members of Congress. He will truly be missed internationally, nationwide throughout New York, but especially in his beloved Harlem where ‘he was the man.’”

Former Assemblymember Keith Wright told the AmNews that Rangel was a “political genius and a personal role model. The Harlem community, the state, and the nation are fortunate to have had Charlie Rangel in our lives. His legacy is cemented in perpetuity.”

During an interview with The HistoryMakers in 2018, Rangel recounted his early years coming of age on the streets of Harlem. “I came up from nothing,” he said, “I was a fatherless high school dropout with a gift of living by my wits and hiding my inadequacies behind bravado.” At the age of 22, he said, “I was pushing a hand truck in the gutters of New York’s garment district for a living…Yet somehow, by age 30, I had acquired three degrees in six years, and was a newly minted lawyer admitted to the New York Bar.”

Rangel’s rise from poverty to leadership in Congress began on June 11, 1930 when he was born in Harlem. Raised by his mother, grandfather, and his uncle Herbert, he attended P.S. 89, Junior High School 139, and later DeWitt Clinton High School, where he did well as a student. After dropping out of high school, he enlisted in the U.S. Army. He served during the Korean War and was seriously wounded in combat, and received the Bronze Star and Purple Heart.

“My heart is broken by the passing of a lion of Harlem today,” Rev. Al Shapton said in a statement. “I met Charlie Rangel as a teenager and we formed a bond that lasted over 50 years. Charlie was a true activist — we’ve marched together, been arrested together and painted crack houses together. After surviving the horrors of the Korean War, he made every day of his life count — whether it was coming home to get a law degree or becoming a fixture on the House of Representatives.”

On the rise

Upon discharge from the military, Rangel enrolled at New York University, earned his B.A. degree in 1957, and three years later, a law degree from St. John’s University Law School. A working man throughout his life, he was fond of recalling his job as a night desk clerk at the Hotel Theresa, Harlem’s Waldorf-Astoria. “At nights when I worked, it was Grand Central Station for the biggest Black stars of stage and screen, the top athletes, the highest rollers, and all the inevitable low-life hangers-on,” he wrote in his autobiography. In 1961, Attorney General Robert Kennedy appointed Rangel assistant U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York. Six years later, he won election to the New York State Assembly.

But only focusing on his first elected office, he misses two highlights of his life: His marriage to Alma Carter in 1964 and the 54-mile trek he made with others from Selma to Montgomery in 1965.

“I cursed every step of those fifty-four miles, wondering how the hell did I start marching with these redneck national guard troops for an escort,” he wrote. “People in every house we passed along the way called us everything under the sun, and threw things at us. Every store played ‘Bye, Bye Blackbird’ from loudspeakers.” One man, he recalled, asked him if he wanted a shower since they were sleeping in tents scattered around the fields. “We met and climbed into this broken down car on a dirt road,” Rangel continued, “and as this overcrowded car took off in the darkness, we saw that we were being followed. Damn, were we scared. We sped up, turned around, and gave up all thoughts of showering –– all we wanted to do was get back to our group.”

Thanks to the influence of J. Raymond Jones, known as “The Harlem Fox” for his political sagacity, Rangel’s political career was launched, having succeeded Percy Sutton for the 11th A.D. It was also the beginning of a lifelong friendship with Sutton that later morphed into the forging of the Gang of Four, including Basil Paterson and David Dinkins. With Rep. Powell battling cancer and spending too much time out of the country, Rangel was among a cadre of young politicians who began to talk about unseating the invincible congressman.

On several occasions, Rangel was in Powell’s company when he often assembled residents to display his power. Once at the Rooster bar, where Powell held forth, “I’d gone alone, which was stupid,” Rangel admitted in his autobiography. Powell had all of his boosters and fans prepared to voice a chorus of “Yes, Congressman!” “I was still brand-new as a district leader, and I was once again overly impressed with the invitation to meet Adam. But the meeting was all about ‘So…you’re the new guy on the block … you’re the smart one …’ You’re this and that. I learned a lesson from that meeting, and I remembered everyone who was there.” For the next few years, he said, the meeting haunted him.

Taking on a legend and establishing his own legacy

On February 20, 1970, Rangel announced his run against Powell, and in doing so, gave up his Assembly seat. As it turned out, Rangel narrowly defeated Powell, never needing the Republican ballot line. “I won the Democratic primary in June by 150 votes,” Rangel said. And he defeated Powell when he took the outcome to the Supreme Court. “All I had to really do,” he said about the contest, “was dominate the vote in my district…and that, you might say, was my margin of victory,” he said.

Rangel hit the ground running, having soundly defeated the Republican candidate in the general election. He was hardly in his seat when he became a co-founder of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) in 1971. The CBC was the initial step in solidifying the gains of the civil rights movement. Among the first legislative moves by Rangel was to distance himself from Powell’s shadow with concerted campaigns against drugs. But he was most proud of his three articles against President Nixon, above and beyond the Judiciary Committee, in 1974. In 1983, Rangel became chair of the Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control and was subsequently appointed a deputy whip for the House Democratic leadership, a position he maintained until 1993.

As the consensus on how to address the drug crisis shifted among progressives, Rangel evolved from a stubborn proponent of using prosecution and law enforcement to stomp out the blight to an advocate for reform. In a 1990 article on the President Bush’s new drug strategy, the AmNews wrote: “he was concerned that ‘there was nothing in the updated strategy which addresses the root cause of drug abuse.’” He went on to say, “The need to attack the root causes of drug abuse cannot be overlooked.”

A year later, under federal legislation authored by Rangel, President Clinton, the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone (UMEZ) was created. It was established to assist residents who had the highest concentration of poverty, according to the 1990 Census. No matter the event, the UMEZ was always mentioned among Rangel’s most significant contributions to the Harlem community. But his crowning achievement as a congressman came in 2007 when he became the first African American to chair the House Ways and Means Committee.

Rangel was also a champion for the Caribbean, advocating first for a normalization of relations between the U.S. and Cuba and later for Haitian refugees. In a 1993 article, Rangel told the AmNews, “It is time to end the Cold War in our hemisphere.” Later, adding “Cuba poses no threat at all to the U.S.”

On behalf of Haitian refugees, Rangel said, “the explosive situation in Haiti demands forthright action by our government to protect Haitian refugees in any way possible.” He added, “With the ever-present threat of violence in Haiti, we must put an immediate end to the deportations. It has been an inhumane policy from the start that we practice against no other nationality.”

As chair of the Ways and Means Committee, Rangel led the economic recovery after a terrible recession in 2008. He played a key role in the Democrats’ landmark health care bill, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. During a committee hearing, Rangel said, “We have a moral obligation in terms of the number of people who have lost their homes, gone into bankruptcy as a result of the costs of providing health care.”

For a congressman who often proclaimed he hadn’t had a bad day since being wounded during the Korean War, there, as he admitted, were several setbacks, none more critical than a string of ethics violations, which he was accused of accepting rent-controlled apartments in Harlem at values far below market. When he challenged those charges, it merely exacerbated his situation and led to disclosures of unpaid taxes. The end result of the ongoing dispute, with Rangel denying any wrongdoing, led to his leave of absence a few days before President Obama enacted the Affordable Care Act in 2010. Eventually, the Ethics Committee found he violated almost all of the charges against him and voted 9 to 1 to censure him. The full House voted unanimously to censure the first representative to undergo such treatment in a generation.

During the 2010 election, Rangel, his reputation somewhat blemished, narrowly defeated the challengers in the Democratic primary. Even so, the handwriting was on the wall, his influence diminished, and he was temporarily relieved of his chairmanship of the Ways and Means Committee but stayed a member of the committee. Among his last acts in Congress before retiring after the 114th Congress was as a ranking member of the Subcommittees on Trade.

His long tenure in Congress may have come to an end but “Lion of Lenox Avenue,” was not without his prestige in Harlem, particularly at the City College of New York where he helmed the Charles B. Rangel Infrastructure Workforce Initiative, fully prepared to usher in the next generation of skilled professionals to meet the demands of a changing industry. Having served in New York’s 15th Congressional District for nearly half a century, his new office at City College has become an incubator, bridging education and opportunity. It was just another way of perpetuating his leadership, carrying on what he had done previously in Congress on the various committees and subcommittees, with UMEZ, and his determination to upend apartheid in South Africa. Even as he basked in the sun on the beach at Punta Cana in the Dominican Republic with his wife, Alma, who died in 2024, reflecting on his two children and grandchildren, Rangel was ruminating on his legacy and other issues still to be resolved.

At the close of his autobiography, he said, “I’ve spent all of my life preparing this case (his meeting with St. Peter). It will include the Caribbean Basin Initiative, the African Growth and Opportunity Act, the Empowerment Zones, and the Rangel Low-Income Housing Credits, among many other things, in the Congressional Record. And if St. Peter’s not overly impressed with my legislative record, then I’ll just have to tell him that I did the best I could. And if I succeed in getting a room with a view, then I can truly say that I haven’t had a bad time.”

A version of this appears in Amsterdam News