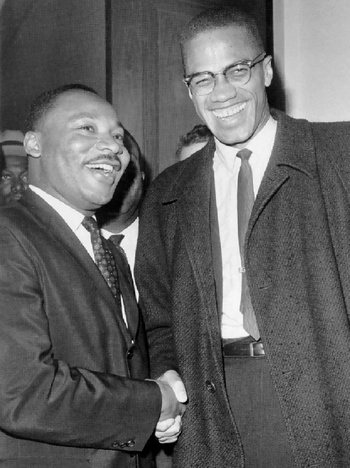

Their one and only meeting lasted barely a minute. On March 26, 1964, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X came to Washington to observe the beginning of the Senate debate on the Civil Rights Act. They shook hands. They smiled for the cameras. As they parted, Malcolm said jokingly, “Now you’re going to get investigated.”

That, of course, was well underway. Ever since Attorney General Robert Kennedy had approved FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s request in October 1963, King had been the target of extraordinary wiretapping sanctioned by his own government. By this point, five months later, the taps were overflowing with data from King’s home, his office, and the hotel rooms where he stayed.

Henry Griffin/AP Photo

Henry Griffin/AP Photo

The data the FBI mined—initially about King’s associations with Communists and later about his sexual life—was used in an attempt to, depending on your point of view, protect the country or destroy the civil rights leader. Hoover and his associates tried to get “highlights” to the press, the president, even Pope Paul VI. So pervasive was this effort that it extended all the way to the small campus in Western Massachusetts, Springfield College, where I have taught journalism for the past 15 years.

In early 1964, King was invited by Springfield President Glenn Olds to receive an honorary degree and deliver the commencement address on June 14.But just days after King accepted the invitation, the FBI tried to get the college to rescind it. The Bureau asked Massachusetts Senator Leverett Saltonstall, a corporator of Springfield College, to lean on Olds to “uninvite” King, based on damning details from the wiretap.

related story

The FBI and Martin Luther King

“I’m trying to wait until things cool off,” King said, “until this civil rights debate is over—as long as they may be tapping these phones, you know.”

Read the full story by David Garrow in the July/August 2002 Atlantic

King’s biographers have recorded little about this episode. Neither David Garrow nor Taylor Branch—who both won Pulitzers for books about King—ever mentioned Glenn Olds by name or title. Saltonstall is relegated to a one-sentence footnote in Garrow’s The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr., a groundbreaking 1981 book that unmasked the Bureau’s extensive surveillance of the civil rights leader. In the hardcover edition of Branch’s 2006 book,At Canaan’s Edge, the third volume of a towering trilogy about America in the King years that took more than two decades to create, the renowned historian wrote that Saltonstall had “helped block an honorary degree at Springfield College, by spreading the FBI’s clandestine allegations that King was a philandering, subversive fraud.”

There was just one problem with this lively statement. Nobody blocked an honorary degree for Martin Luther King at Springfield College.

It was a small lapse by a formidable researcher and masterful storyteller. But lurking beneath this mistake is a great and almost entirely untold story about the most important figure of the civil rights era and a maverick college president facing his moment of truth.

The students in Springfield’s class of 1964 lived a Forrest Gump-like connection with U.S. history. Born just after the attack on Pearl Harbor, they came to college at the dawn of a new decade. In the fall of their freshman year, Massachusetts’ native son John F. Kennedy appeared at a rally in downtown Springfield one day, and got elected president of the United States the next. In the fall of their senior year, they flocked to the few black-and-white televisions on campus to join America’s grim vigil when JFK was shot. The following June, they expected to turn their tassels from right to left in the presence of Martin Luther King.

For most of their college days, there was an innocence to this group of American youth, at a time just before the ’60s became The Sixties. During their freshman year, they wore beanies. Their social worlds included hootenannies, panty raids, and carefully regulated visiting hours in single-sex dorms, with strict rules of “doors open, feet on the floor.” Many students of the almost exclusively white class learned The Twist from Barry Brooks, a popular “Negro” student from Washington, D.C., who earned election to the Campus Activities Board.

These students, at the tail end of the so-called “Silent Generation,” were less inclined to question authority or conventional wisdom than their younger siblings would later be. They’d also chosen to attend Springfield College, an old YMCA school, known as the birthplace of basketball and best regarded at the time for producing wholesome teachers of physical education. “It was,” says Barry Brooks, “sort of an apple pie kind of place.”

Members of the class were only vaguely familiar with Glenn Olds, who served as college president from 1958 to 1965. He was a trim and conservatively dressed man with receding blond hair and an engaging grin. He sometimes hosted groups of students at his on-campus house, serving apples, cheese, and water. He never drank alcohol or caffeine. He began each morning with calisthenics.

Glenn Olds meets with Nigerian students at Springfield College in 1963. (Springfield College Archives)

Glenn Olds meets with Nigerian students at Springfield College in 1963. (Springfield College Archives)

But there was nothing drab about him. Olds was a man marked by dazzling dualities. Raised by a Mormon mother and a Catholic father, he became a Methodist minister. Working from a young age as a logger and a ranch hand, he went on to get a Ph.D. from Yale, penning his dissertation on “The Nature of Moral Insight.” While at Springfield, he maintained an office in Washington, working on progressive programs for Democratic presidents—the Peace Corps for Kennedy and VISTA for Johnson—but later worked full-time for Nixon (and even later got fired by him). He was married three times and divorced twice—all to Eva Belle Spelts, a former “Ak-Sar-Ben Princess” from Nebraska. They are buried together on a mountainside in Oregon.

Glenn Olds would later go on to take over the presidency at Kent State in 1971, the year after National Guardsmen shot and killed four students who were protesting the Vietnam War. In 1986, without any experience as a political candidate, he would run as a Democrat for U.S. Senate from the state of Alaska, getting 45 percent of the vote, but losing to incumbent Frank Murkowski, whose daughter holds the seat to this day.

Olds could be an intimidating man. As a youngster in Oregon, he made money for his family by starring in “curtain raisers” at boxing matches. According to his son, Dick Olds, the founding dean of the UC-Riverside Medical School, Glenn never lost his swing. “I still remember vividly an event that occurred at Springfield College,” says Dick, who lived on campus from age 8 to 15. “There was a drunk guy in the student union. He was yelling stuff and knocking some things on the ground. My father went over to talk to him and tell him that he needed to leave. The guy took a swing at my dad. My dad knocked him out, down on the floor, one punch. I’d never seen anything like that.”

But Glenn Olds was also an ardent pacifist. As a senior at Willamette University, he stood with other clergy on the night of the Pearl Harbor attack, preventing marauders from charging into a Japanese-American farming enclave at Lake Labish. He sought religious exemption from the war as a conscientious objector—even as both of his brothers fought, one of them coming home wounded from Okinawa. In 2004, two years before his death, Olds told me that he had been disowned by his father, Glenn Olds Sr.: “He’d rather see a son of his dead than refuse to put on the uniform.” That did not dissuade him. “I took the pacifist position to be essentially the one Jesus took,” Olds said. “I thought I was on good historic ground.”

Olds recalled Hoover’s deputy playing him a tape “filled with vulgarity. I said, ‘If you go public with this, I’m happy to hear it. Otherwise I don’t want to hear any more of it.’”

During summers, Olds offered the Springfield campus as a site for Peace Corps training. At the 75th anniversary of the college in 1960, he brought in speakers who were renowned pacifists: Aldous Huxley, Margaret Mead, and Norman Cousins. So it was no real surprise when he sought out Martin Luther King as a commencement speaker in 1964.

related story

King’s Letter From Birmingham Jail

“One may well ask, ‘How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?’ The answer is found in the fact that there are two types of laws: there are just laws, and there are unjust laws.”

Read the full story in the August 1963 Atlantic

By this point, King had been established as a paragon of pacifism, and his movement had started to gain national traction. Just a year before, in the spring of 1963, the fire hoses and gnashing dogs of Bull Connor’s Birmingham, juxtaposed with the quiet dignity of black children and teenagers, had awakened much of America to the brutality of racism. A few months later, on a hot day in late August, the March on Washington had not devolved into a blood bath as some leaders feared. Instead it had become a beacon of peace and unity.

But there was, of course, the backlash. One day after President Kennedy first introduced the Civil Rights Act, Medgar Evers was killed by a white supremacist. And just 18 days after the March on Washington, four young girls in white dresses were murdered by a dynamite blast in a Birmingham church.

Two months after that, Martin Luther King watched the Kennedy assassination from a television in his Atlanta home. Turning to his wife Coretta, he said, “This is what’s going to happen to me. This is such a sick society.”

Glenn Olds had a couple of connections with the civil rights leader. One was through Andrew Young, King’s close friend and a top associate with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Olds had come to know Young at a youth leadership conference and on a Methodist preaching tour. The other connection was through a fellow college president in Massachusetts, Harold Case of Boston University, where King had gotten his doctorate. Olds apparently made his first contact with King in mid-March. A surviving letter in the Springfield College archives from Director of Public Information George Wood is dated March 24, 1964. Addressed to King at his home on Auburn Avenue in Atlanta, the letter starts out:

Dear Mr. King,

The office of Dr. Glenn A. Olds, our president, has just informed me that you have accepted the invitation to be our Commencement speaker on Sunday, June 14, 1964.

The letter deals with logistical matters and also asks for “a current biography and as many glossy photographs of you as can be spared.”

Martin Luther King’s completed cap and gown order form (Springfield College Archives)

Martin Luther King’s completed cap and gown order form (Springfield College Archives)

Two days later, The New York Times reported that Olds and two others had been “named today to develop plans for key parts of the Administration’s anti-poverty program, now pending in Congress.”

That was also the day Malcolm X and King had their chance encounter in Washington. Malcolm was at a crossroads, 18 days after breaking from the Nation of Islam and 18 days before embarking on his pilgrimage to the Mideast. King was at the apex of his fame. He knew that the stakes surrounding the Civil Rights Act were high. All the restraint he had called for, all the belief in the American system, all of his credibility about the arc of the moral universe bending toward justice was invested in the passage of this law, widely regarded as the most important in the 20th century.

He knew it would not be easy. Just four days later, Southern senators launched what would prove to be an epic 10-week filibuster of the bill. Georgia’s Richard Russell publicly proclaimed, “We will resist to the bitter end any measure or any movement which would have a tendency to bring about social equality and intermingling and amalgamation of the races in our states.”

Far more secretively, just three days after that, the FBI turned its attention to keeping Martin Luther King away from Springfield College.

The initial April 2, 1964, memo from F.J. Baumgardner to Head of Domestic Intelligence W.C. Sullivan was heavily redacted when it was declassified years later, but it still spelled out the plan quite clearly. According to Baumgardner, the FBI had learned that both Springfield and Yale were considering King for honorary degrees. He said the Bureau was “initiating appropriate checks as to the availability of such established and reliable sources at these institutions which would permit the heading off of the conferring of honorary degrees to King.” The strategy had already “prevented King from getting an honorary degree from Marquette University.”

Baumgardner said the plan had been approved by J. Edgar Hoover: “The Director noted ‘OK’ relative to these intentions of ours.”

The name of the “established and reliable” source—the person who would be sent to intercede at Springfield College—is redacted in every instance except one. That momentary lapse by the person with the dark black marker fills in the critical puzzle piece: “It should be made clear to Saltonstall[emphasis added] that the information is being given him in the strictest of confidence with the thought that he might desire to use it in preventing King from receiving an honorary degree from Springfield College and thus save that institution from embarrassment because of King’s connections and character.”

A key name is accidentally revealed in an FBI memo from April 2, 1964, which details the plan to block King’s commencement speech. Click the image above to view the full memo in a new window. (Springfield College Archives)

A key name is accidentally revealed in an FBI memo from April 2, 1964, which details the plan to block King’s commencement speech. Click the image above to view the full memo in a new window. (Springfield College Archives)

So who was this Leverett Saltonstall? He was 71 at the time, a World War I veteran in the midst of his fourth and final term as a Republican senator from Massachusetts. He was Boston Brahmin to the core: he had Mayflower ancestry, and was the 10th generation of his family to attend Harvard, where he rowed crew and played hockey.

On April 10, 1944, when Saltonstall was a third-term governor of Massachusetts, he had been featured on the cover of Time. That article had described him in memorable fashion:

His engagingly homely face is his No. 1 political asset, with its drooping eyelids, lean cheeks, long nose, wide-spaced teeth, and the famed ‘cow-catcher chin.’ That reassuring face has been termed ‘a well-worn American antique’ and ‘the most distinctive face in U.S. public life.’ Deviousness would have a hard time finding a hiding place there. It is a face New Englanders trust.

As a corporator for Springfield College—an elected but largely ceremonial role once played by John F. Kennedy (the 1956 commencement speaker)—Saltonstall was seldom consulted on college business. But in this instance, he was brought deeply into the drama, as detailed by a second FBI memo—a fascinating one penned the evening of Wednesday, April 8, by Cartha “Deke” DeLoach, one of Hoover’s top associates.

DeLoach wrote that he had met with Saltonstall on April 7, and that the senator’s response to the wiretap details on King had been stark. He “was shocked to receive this information. He stated it was hardly believable. He said if it were not for the integrity of the FBI, he would disbelieve such facts.”

DeLoach reported that the senator felt “duty bound” to share the information with Glenn Olds, whom he “described … as a very outstanding individual who could be trusted implicitly.” (Olds’ name is redacted throughout, but obvious through context.)

An FBI memo from April 8 recounts a meeting with college president Glenn Olds. Click the image above to view the full memo in a new window. (Springfield College Archives)

An FBI memo from April 8 recounts a meeting with college president Glenn Olds. Click the image above to view the full memo in a new window. (Springfield College Archives)

Saltonstall did indeed meet with Olds later that day, and he spread the FBI’s dirt on King—but apparently had some misgivings about doing so. He called the Bureau right back and asked if DeLoach would be willing to meet directly with Olds. DeLoach agreed to meet with the Springfield president at the FBI office on April 8 at 4 p.m.

According to DeLoach’s memo, Olds “opened the conversation by stating that he fully recognized the necessity to keep the information concerning King in strict confidence.” Olds was “very shocked” by the information provided by Saltonstall, who “had insisted that Reverend King be prevented from making the commencement address at Springfield College.”

Despite this insistence, Olds “stated that due to the fact that he will keep this information confidential, it would be impossible … to ‘uninvite’ King to make the appearance at Springfield College.”

Though he didn’t deliver the goods, Olds did leave the door ajar. A few sentences later, DeLoach reported that Olds “said he wanted to think about the possibility of preventing King from making the address but at this step of the game he did not see how it could be done.”

Before leaving, Olds “expressed a desire to shake hands with the Director some day” and indicated that Springfield College had extended to Hoover “two invitations in the recent past to receive an honorary degree and make the commencement address.”

When I spoke to him 40 years later, in 2004, Olds—then a man of 83 with some health issues—claimed that he had received a follow-up call in which DeLoach played some of the wiretapped material: “Hoover’s deputy called me to dissuade me from giving him a degree. He started to play a tape, ostensibly of King. It was filled with vulgarity. I said, ‘Are you willing to go public with this? If you go public with this, I’m happy to hear it. Otherwise I don’t want to hear any more of it.’ He said, ‘God, we can’t go public.’ So I hung up on him.”