One of the biggest bait and switches ever pulled on American citizens was the ruse of collectively shared farming. It was a simple but effective long con. Farmers and plantation owners convinced newly freed slaves and poor people to work a portion of their land in exchange for a share of the harvest.

In theory, this plan incentivized the workers to produce the biggest crop possible, and the landowners could maximize the use of their land, sharing the profits with labor. This system of “sharecropping” seemed like a perfect plan.

But this farm-tenancy system eventually went south. Landowners found ways to bilk the sharecroppers out of their portion of the profits by charging them for food, housing, the use of equipment, interest on loans and anything else they could conjure up. The workers eventually ended up as indentured servants—in debt to the landlords, giving their blood, sweat and tears for a payday they never received.

Incredibly, sharecropping was never outlawed. The mechanization of farming made it impractical, and the people who had been tied to the land eventually realized the nature of the con. But to this very day, if you could convince people to give their blood, sweat and tears for no pay except the promise of fortune and success down the road, you could start your own sharecropping system. Fortunately, no company is arrogantly evil enough to convince poor people to work for free while the business rakes in billions in profit, refusing to compensate the workers who sacrifice their bodies and minds …

… except for college athletics.

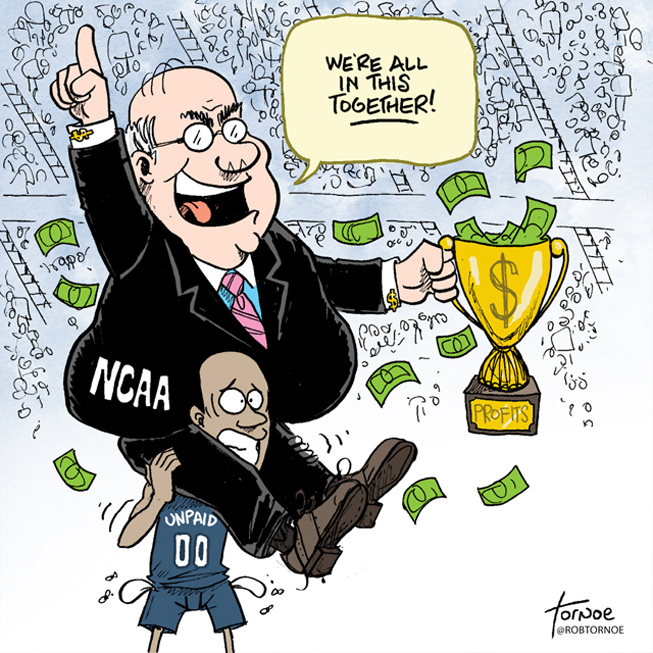

Funded by the federal government (that means us), the National Collegiate Athletic Association is nominally a nonprofit organization. Technically, however, the NFL (which made about $13.3 billion in 2016) is also a nonprofit because it distributes all the money it makes to its individual franchises. Calling them “not-for-profit” organizations is like saying Beyoncé and Jay Z are poor because Blue Ivy is going to end up with all the money anyway.

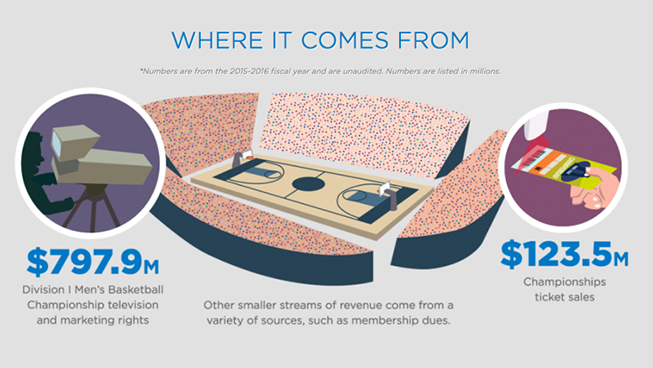

NCAA revenue, 2015-2016 (NCAA)

The NCAA makes around $1 billion a year (figures for 2016 haven’t been released yet; it presumably takes quite a while to count the piles of money) on college athletics. Eighty percent of the NCAA’s revenue comes from the media rights to the NCAA tournament. If you add in the $3.4 billion for college football (the playoff championship is owned by the 125 Football Subdivision, or FBS, schools), the total revenue for college sports tops $4 billion—almost all of it from football and basketball. Four billion. Now guess how much players get.

They get food, of course. They get to live in college dorms, so there’s free housing. Depending on which school you attend, there’s a $2,000-$5,000 stipend for the year (which amounts to $1-$2.50 per hour). There’s the free athletic gear. But the real allure of college athletics is the opportunity for fame, athletic glory, free education and more money than they could ever count.

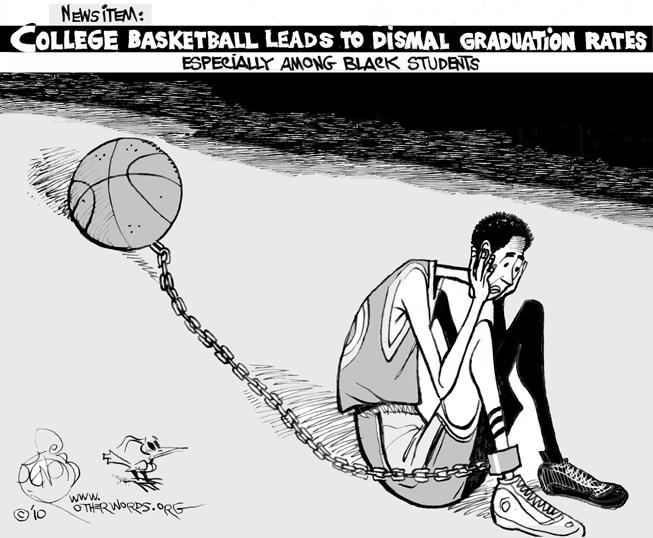

Welcome to the new sharecropping.

Just as in sharecropping, when you talk about the student-athletes in money-earning sports, you’re really talking about black people. In 2012, the latest year for which figures are available (pdf), black players made up 51.6 percent of FBS football players (far more than their 13 percent of the American population) and 57.2 percent of Division I basketball players. For years, colleges have made hundreds of millions of dollars on the backs of these athletes with no regard for their future, and no one cares—simply because they’re black.

That’s not supposition. That is what a recent study by UMass Amherst associate professor of political science Tatishe Nteta found. Nteta and researchers interviewed subjects on a number of topics and “devised a survey that weighed variables like age, sex and interest in college sports and negative attitudes towards African-Americans, a measure he calls racial resentment.” Nteta found that the subjects who held the most racial biases statistically opposed paying college athletes. Even white subjects who weren’t “racially resentful” leaned toward not paying college athletes when they were shown a picture of black athletes alongside the question.

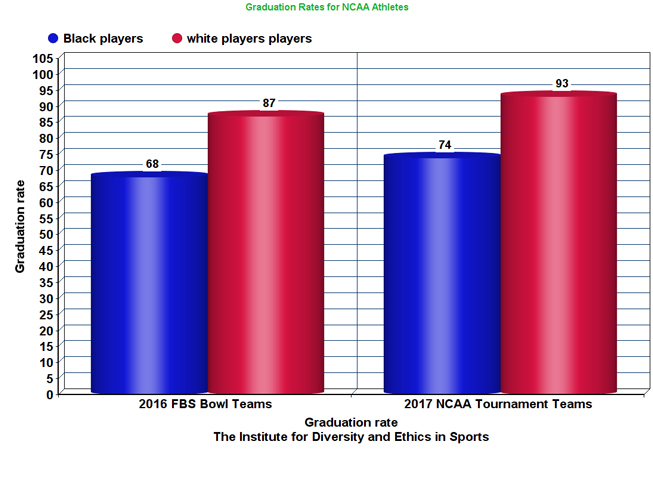

Of course, there are arguments against paying college players. Some people say that it turns college athletics into professional sports (even though teams, coaches, sponsors, television networks and everyone else involved with college sports make millions; it is already professional sports). Others argue that the players get a free college education (they don’t; athletic scholarships are one-year, renewable offers, and are only good as long as you can play) and kids are given a chance to play professional sports (less than 2 percent of players ever play professionally). The greatest argument is that college players basically get a degree for free, but every metric shows that it is the white players, not the black players, who end up with degrees.

During the 2014-2015 academic school year, black men were 2.5 percent of undergraduate students but 56.3 percent of football teams and 60.8 percent of men’s-basketball teams. The average graduation success rate for college football players in 2016 was 68 percent. For white football players, it was 87 percent. College basketball is even worse—it graduated only 53 percent of its black ballers. If any other business in America had that much racial disparity in any of its industry practices, it would either be sued into oblivion or shut down by the government.

But not on these special plantations, which get to do whatever they want.

Data from Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sports/Online Chart Tool

Only 18 percent of college basketball coaches (pdf) are black, while only 8 percent of FBS head coaches are African American. The billions of dollars earned by the black sweat dripping onto the beautifully manicured grass and waxed courts end up in the pockets of white coaches, white administrators and white network owners, and benefit white students at predominantly white schools.

So tomorrow, while you watch the NCAA Final Four with millions of others, don’t imagine yourself making a last-second jump shot. Instead, imagine that you are one of the top people working in your field today, and you are recruited by a multibillion-dollar corporation. Suppose the job is incredibly difficult and requires you to travel, risk injury and endure bodily pain, but you know that your talent and expertise could make the company millions of dollars, give it global brand recognition and garner it worldwide acclaim. What would you think if—when you sat down to discuss compensation—the recruiters told you, “Oh no. We won’t be paying you. We expect you to do this for free.”

Would you think they were evil? Would you accuse them of being exploitative users? Would you call them con men and tell everyone working there that they should strike, and beg everyone else to boycott their product? Or, as you stormed out, would you tell these new-millennium plantation owners that you are neither a servant nor a field hand, and if they expect to turn you into a sharecropper …

… they must be out of their cotton-picking minds.