Noah Wills and Jonathan Davis fill out applications to open checking accounts during the Black Transfer Challenge at Citizens Trust Bank in Atlanta. The campaign urges opening accounts at black-owned banks and institutions. (Kevin D. Liles for the Washington Post)

By Tracy Jan, Washington Post

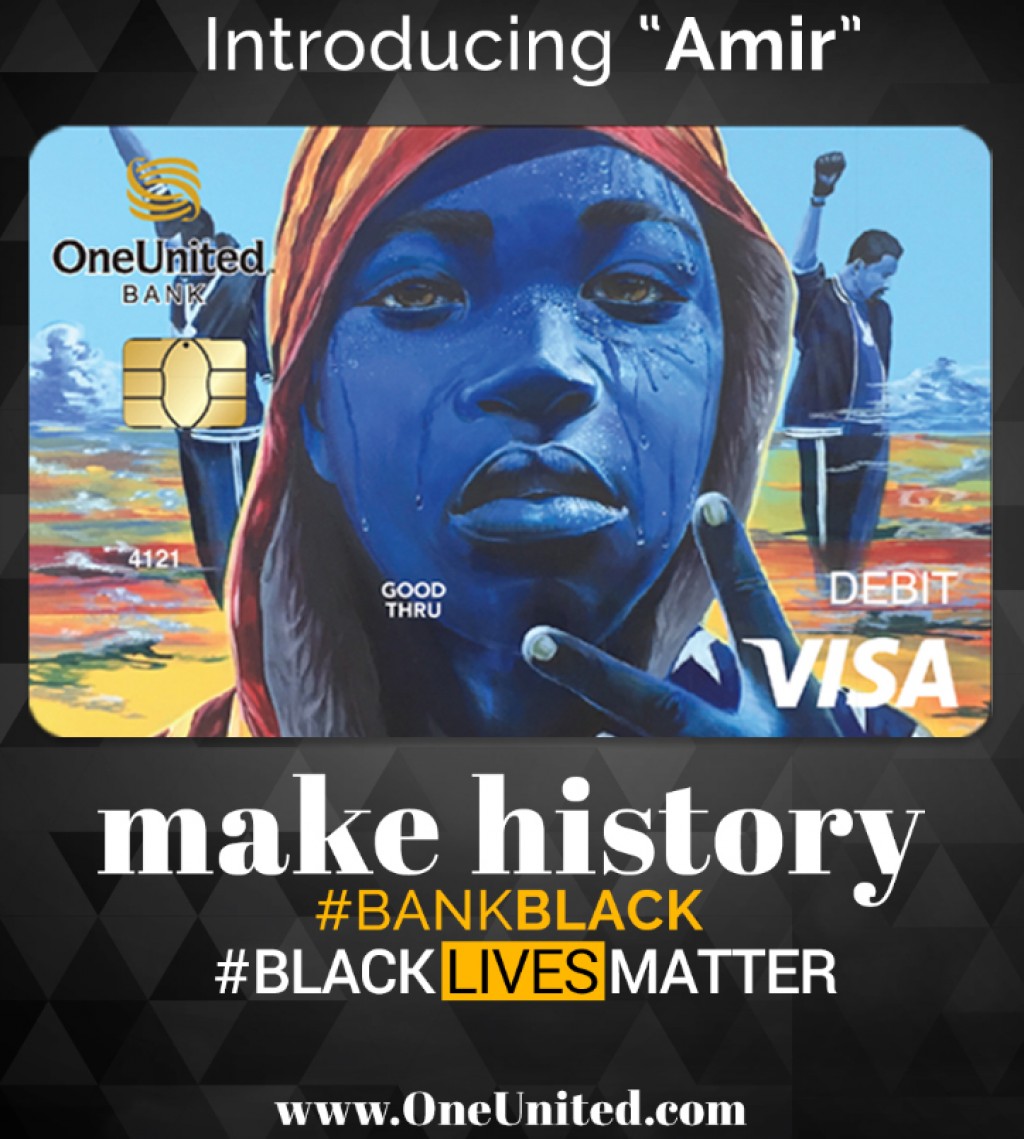

Greg Akili had just finished paying for his $9 tuna melt at a diner in South Central Los Angeles when his waiter lingered to chat. Akili’s debit card — featuring a painting of a black youth wearing a hoodie and the famous image of the 1968 Olympic medalists, heads bowed, fists raised — had caught the young man’s eye.

For the third time that day, Akili lit up and launched into a conversation he’s been having daily, with strangers and friends alike. The 68-year-old community organizer waved his hands in the direction of his new bank about five blocks up Crenshaw Boulevard: OneUnited, the largest black-owned bank in the country.

“I’ve been trying to convince as many people as I can to open up accounts with black banks and invest in our own community,” Akili said, recounting the recent interaction. “I talk about this almost every time I use my card.”

This new card is part of a rescue effort for black banks that was launched with much fanfare last summer. But the campaign is going to need heroic measures if it is really going to save black financial institutions.

The aim of the movement is clear: bolster black banks — and in the process, uplift a community that has been systematically marginalized for generations.

A man enters Citizens Trust Bank during the Black Transfer Challenge, hosted by HBCU Wall Street and Bank Black organizations. (Kevin D. Liles for the Washington Post)

By “banking black,” organizers say, African Americans have the power to help each other buy homes, build businesses and create jobs — markers of wealth that have eluded a disproportionate number of blacks.

But many of these banks are struggling to survive in the wake of the financial collapse. And despite a spate of celebrity endorsements, the drive to deliver meaningful equality by reviving financial institutions remains a long shot.

Forty-two percent of African Americans own their homes, compared with 72 percent of whites, according to 2016 Census Bureau data. Nearly a fifth of black households do not even use banks, compared with 3 percent of white households, the FDIC reports. The continued disparity in access to financial services exposes black families to loan sharks charging exorbitant interest rates and fees, which can trap borrowers in a cycle of debt.

“It’s a challenge to build up the financial assets of this community,” said Russell Kashian, an economist at the University of Wisconsin at Whitewater whose research focuses on minority-owned banks. “Efforts to get depositors in there will augment the profits and sustainability of these banks. But if people don’t support them, these communities can become bank deserts.”

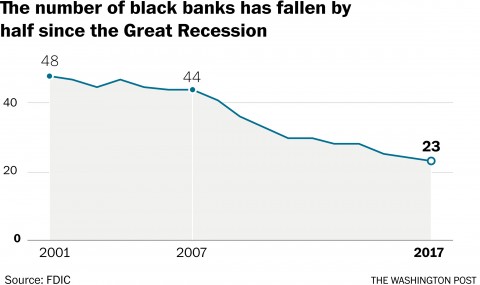

There are 23 black banks today — far fewer than during segregation, when they were the only option for many African Americans. Their combined assets total just $5.5 billion, a small fraction of the assets of banking behemoth Wells Fargo, which has $1.9 trillion.

After 30 years of banking with Wells Fargo, Akili made the switch to OneUnited in February, the same month the bank announced a partnership with Black Lives Matter and debuted its debit card depicting the youth in the hoodie.

Cardholders can make automatic, regular donations to Black Lives Matter, founded after 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was shot to death by a neighborhood watch volunteer in Florida.

The first black-owned bank to offer Internet banking, OneUnited was well positioned to take advantage of the #BankBlack wave with its mobile and online services. The Boston-based bank with branches in Los Angeles and Miami added $6.7 million in deposits in the second half of 2016, according to FDIC records. It went from opening an average of 50 new accounts a day to more than 1,000 a day, said Teri Williams, the bank’s president and chief operating officer.

“It reflects a change in the understanding of the power of our dollars,” Williams said, “and the fact that we need to use our money more purposefully.”

Fresh off a tour in March, Michael Render sauntered into a bank tucked into a shopping complex in a leafy neighborhood on the southwest side of Atlanta. The 41-year-old rap artist, professionally known as Killer Mike, was exhausted after performing in 36 cities over six weeks, but he had a cause to promote.

Render, an early advocate of the #BankBlack movement, was hoping to persuade potential customers in his home town to move their money from mainstream banks.

The rapper arrived at the branch of Citizens Trust Bank without an entourage and spent 45 minutes shaking hands. He shared his own experience of getting rejected by large white-run institutions for loans for his chain of barbershops.

Michael Render, a.k.a. “Killer Mike,” visited a branch of Citizens Trust Bank in Atlanta in March. (Kevin D. Liles for the Washington Post)

A black bank, he told visitors, is more likely to approve loans to grow his business because it understands the cultural significance of barber shops. He has used black banks his whole life, following the example of his grandparents, who raised him.

“I am making sure my community will have institutions that will lend them money to start businesses and have mortgages,” Render said later in a phone interview. “Nobody is going to swoop in and save the African American community. The community has to take care of itself.”

By the end of the day — with Render’s help — Citizens Trust had netted 40 new accounts.

Render is credited with having steered thousands to open accounts at black banks. Last July, after the shooting deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile by police in Louisiana and Minnesota, Render called in to an MTV and BET town hall and told the audience not to riot in the streets but to “take our warfare to financial institutions.”

Solange Knowles, Usher, Charlamagne Tha God and other celebrities also joined the bank movement to protest the long string of police killings of black citizens — 50 years after the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. exhorted black Americans to reject violence and harness their collective economic might to strengthen black banks.

Render’s goal at the time was to get 1 million Americans to deposit $100 each in a black bank. Within five days, Citizens Trust reported almost $1 million in deposits. By December, the bank had 10 times as many new accounts as it did in 2015, according to Citizens Trust; the 9,600 new accounts yielded $13 million in deposits.

Large mainstream banks launched their own efforts to win back African Americans customers. Wells Fargo, which has a branch in Atlanta across the parking lot from Citizens Trust, recently announced a $60 billion mortgage lending goal to increase the number of black homeowners.

But Render, like many others, is skeptical. Wells Fargo, the largest home mortgage originator in the country, had previously paid $175 million to settle a U.S. Justice Department lawsuit accusing the bank of steering thousands of black and Hispanic borrowers into subprime mortgages and charging them higher fees and rates than white borrowers with similar credit profiles.

“If major corporations are swooping in out of nowhere and saying, ‘Hey, we have this for your people,’ it’s because they see you doing it for yourself,” Render said.

Despite high aspirations, the #BankBlack campaign has produced mixed results. Many of the banks, from Chicago to Durham, N.C., experienced an immediate surge in deposits last summer when activists launched a text-message campaign calling on individuals to move their money into black banks — only to see the funds ebb away by the end of the year.

Half of the banks, including Citizens Trust, ended 2016 with a drop in deposits, compared with when the push began last July, according to an analysis of Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. data. Eleven banks lost money. One — Seaway Bank in Chicago — went out of business in January.

“A lot of these banks need a lot of work across the board. We don’t want to bank black arbitrarily and bank bad,” said Robert Herring, one of the co-founders of BankBlackUSA, a grass-roots group that formed over social media last summer. “We can’t say, ‘Hey, everyone jump ship,’ and the new ship has holes in it.”

“A lot of these banks need a lot of work across the board. We don’t want to bank black arbitrarily and bank bad,” said Robert Herring, one of the co-founders of BankBlackUSA, a grass-roots group that formed over social media last summer. “We can’t say, ‘Hey, everyone jump ship,’ and the new ship has holes in it.”

Black banks reflect the economic profiles of their customer base, analysts and bank executives say. Located predominantly in working-class neighborhoods, they cater to a clientele many of whom may not meet the credit requirements of mainstream financial institutions.

Black banks, on average, are five times as likely as traditional big banks to back mortgages for properties in low- to moderate-income neighborhoods, according to the FDIC. As a result, they were hit hardest by the recession, when a disproportionate share of African Americans lost their jobs and could not make their loan payments.

“When the American economy catches a cold, that means African Americans have pneumonia,” said B. Doyle Mitchell Jr., president and CEO of the black-owned Industrial Bank, with was started by his grandfather in the District in 1934.

Those economic realities make black-run institutions more vulnerable to financial shocks, even as they balance risk and profit goals with their mission of lifting the black community.

OneUnited drew the ire of Boston’s black community when it foreclosed on a historic black church that failed to repay its loan. The years-long proceedings ended in court, where a federal bankruptcy judge ruled in the bank’s favor.

Many black banks, including Industrial, do not judge loan applicants on credit scores alone; they also take into account life’s hiccups like a divorce or car accident, as well as individual character and financial plans, Mitchell said. But black banks, like all banks, are ultimately in the business of making money.

“Can a black person just walk into a black bank and expect to get a loan? Absolutely not,” Mitchell said. “We have to be prudent in the decisions that we make. We are a business, not a charitable organization.”

Even so, Industrial modified home loans and dropped interest rates to help customers through the recession instead of resorting to foreclosures, Mitchell said.

Other black banks introduced products tailored to customers with checkered credit histories. Citizens Trust launched the “Privilege card” in November for customers with poor credit scores, charging higher interest but offering the opportunity to rebuild credit instead of borrowing from pawnshops. Liberty Bank in New Orleans partnered with U.S. Black Chambers Inc. on a low-interest credit card.

But while the #BankBlack movement helped Industrial gain about 5,000 new accounts between last July and December, Mitchell said simply depositing $100 into a savings account would not make a difference to a bank’s long-term viability.

“You can’t just give black banks your piggy bank,” Mitchell said.

Advocates of the #BankBlack movement acknowledge they are competing against banking giants with larger branch networks, extensive marketing and often superior technology.

“When the doors of integration opened, we thought we were always going to get better services or products with the white institutions, and black banks became the banks of last resort,” said Michael Grant, president of the National Bankers Association, a lobbying group for minority-owned banks.

Black banks peaked at more than 100 during the Jim Crow era. Their decline accelerated with the Great Recession, dropping from 44 in 2007 to 23 today after banks were forced to merge or close. William Michael Cunningham, a Washington-based analyst who specializes in minority-owned banks, predicts there will be seven left by 2028.

A sustained #BankBlack movement can slow that decline, he said but not reverse it.

“It helps the banks out. But it will not move the needle in the long term,” said Cunningham, the chief executive of Creative Investment Research.

To survive, black banks must expand beyond their historic base in the African American community.

Chiké Okonkwo, an actor who stars in the BET series “Being Mary Jane,” said the campaign welcomes anyone who “wants to use their privilege to benefit others.”

About a quarter to a third of the customers at black-owned banks are not black, and several banks are pushing aggressively to diversify their clientele, according to the National Bankers Association.

OneUnited introduced a new debit card with Black Lives Matter in February. (Courtesy of OneUnited)

UAW-Ford made headlines in November when the union deposited $1.5 million with First Independence, a black-owned bank in Detroit.

Temple Israel, a Reform Jewish synagogue in Boston, is exploring the idea of encouraging its 4,000-member congregation to open personal accounts at OneUnited. The bank president is slated to meet with the congregation in April.

“We teach that organized people and organized money is power,” said Matt Soffer, a rabbi at Temple Israel. “And if there is a movement to organize money to uplift these communities that have been systematically oppressed, anything we can do to help people grow their economy is the definition of justice in the most Jewish sense.”

Activism gives Americans the opportunity to confront their darkest history, said Okonkwo, who played a freedom-fighting slave in “The Birth of a Nation,” the 2016 movie about Nat Turner’s 1831 Virginia slave rebellion.

Okonkwo says he takes time every day to educate the baristas and gas station attendants he encounters in Los Angeles — or any cashier who comments on his visually striking debit card — about why he moved his money to a black-owned bank.

“If you’re a white ally of Black Lives Matter or any person who thinks it’s wrong that black people in America are still facing some of the issues that Martin Luther King was facing in the 1960s,” he said, “then put your money where your mouth is.”

Tracy Jan covers the intersection of race and the economy for The Post. She previously was a national political reporter at The Boston Globe.

Follow @TracyJan