Pioneering psychiatrist, Dr. Phyllis Harrison-Ross, passes at 80

By Herb Boyd

There’s a photo of Wayne State University’s College of Medicine graduating class in Detroit in 1959. Of the 66 graduates, …

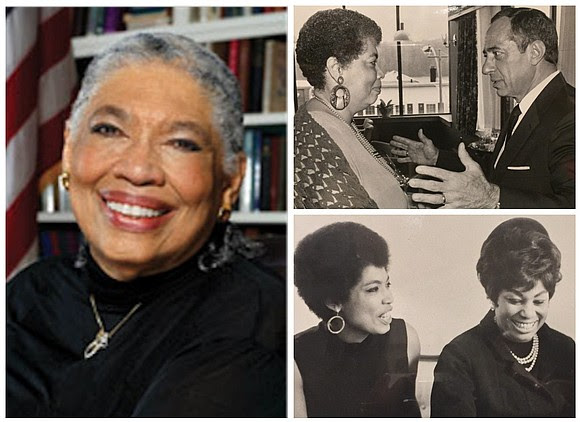

Dr. Phyllis Harrison-Ross with Gov. Andrew Cuomo (top) and American soprano singer Leontyne Price (bottom)

One of her major concerns was about the mental health of people in custody and how to improve their contact with relatives and loved ones on the outside. “The most important thing is keeping that connection with family and keeping it in a reasonable way—not having to make those long, stressful trips,” she told a reporter in conjunction with her role as chair of the New York Society for Ethical Culture’s Social Services Board, which manages the televisiting program for inmates. “That connection helps enormously with reducing recidivism and aids in the mental health of both the child and the incarcerated parent.”

More than anyone Harrison-Ross was aware that such a program to facilitate contact between prisoners and family was not an end-all; even so, she contended, “That’s not because of some lack of moral conviction in that family, it’s because this is a major traumatic occurrence in their life, and there’s no place to turn, no support. We provide these children with that support—that’s how we’re going to break the cycle of incarceration.”

Two major catastrophes—the attack on the World Trade Center and the Katrina Hurricane—required her mental health expertise, and subsequently she volunteered to preside of All Healers Mental Health Alliance. She was no stranger to the media, and many may recall the interview Sheryl McCarthy conducted with her on CUNY TV. For more than a quarter century she was a member of the board of directors of Children’s Television Workshop, producers of “Sesame Street.” As mentioned above, she began using teleconferencing to do psychiatric treatment, supervision and training as well as televisitation to incarcerated or otherwise institutionalized individuals and families.

Harrison-Ross authored numerous articles, reviews, chapters in textbooks and research papers. She published two books on child and adolescent development, “The Black Child—A Parent’s Guide” (with Barbara Wyden) and “Getting it Together,” a textbook for junior and senior high school students who are reading on a fifth-grade level.

But the writing and research were often overshadowed by her dedication to prison reform and vigilantly keeping tabs on the condition of inmates, none more controversial than the death of Bradley Ballard, who died at Rikers Island in 2013. For six days he lay dead in his cell, covered with feces and ignored by supervisors. Harrison-Ross, in her capacity as the commissioner of the oversight panel, was furious, and she recommended that the Department of Justice open a criminal investigation and a more comprehensive investigation into the Rikers Island facility.

This action was typical of her resolve, whether on prison affairs or working in the mental health area. One of her last public appearances was on a panel to discuss the legacy of Dr. Kenneth and Mamie Clark and their role in founding the Northside Center for Child Development, where she was a board member for years.

Her words about the incomparable devotion of the Clarks to child development mirrored her own contributions, and we would need a few more pages to fully cover her expansive career and service.

The funeral or memorial services are as follows:

Viewing, Jan. 24, 4 p.m. to 8 p.m., Benta’s Funeral Home, 630 Saint Nicholas Ave., New York, N.Y., 212-281-8850.

Service, Jan. 25, 11 a.m., The Society for Ethical Culture, 2 W. 64th St., at Central Park West, New York, N.Y., 212-874-5210.