By Herb Boyd and Cinque Brath —

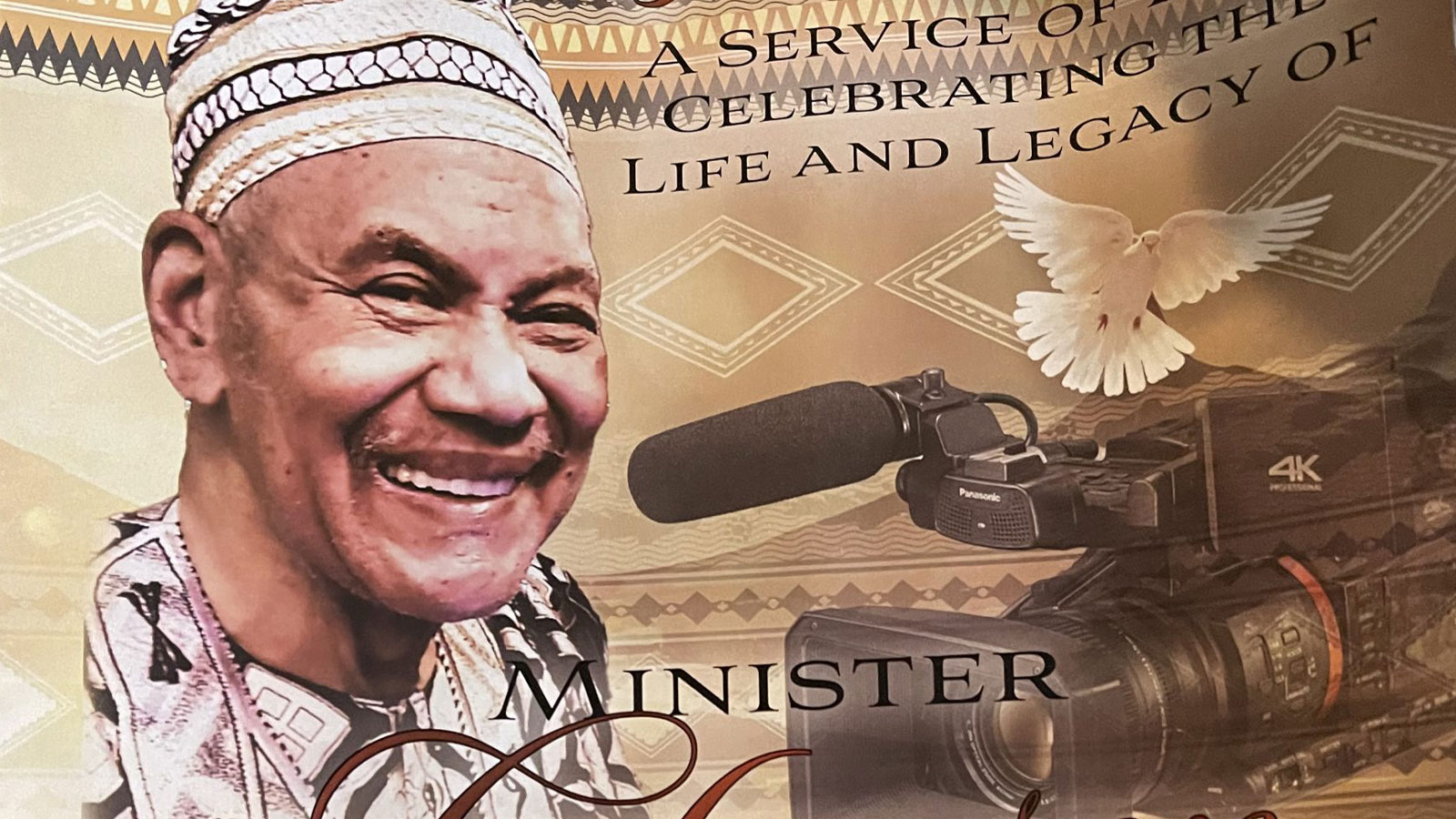

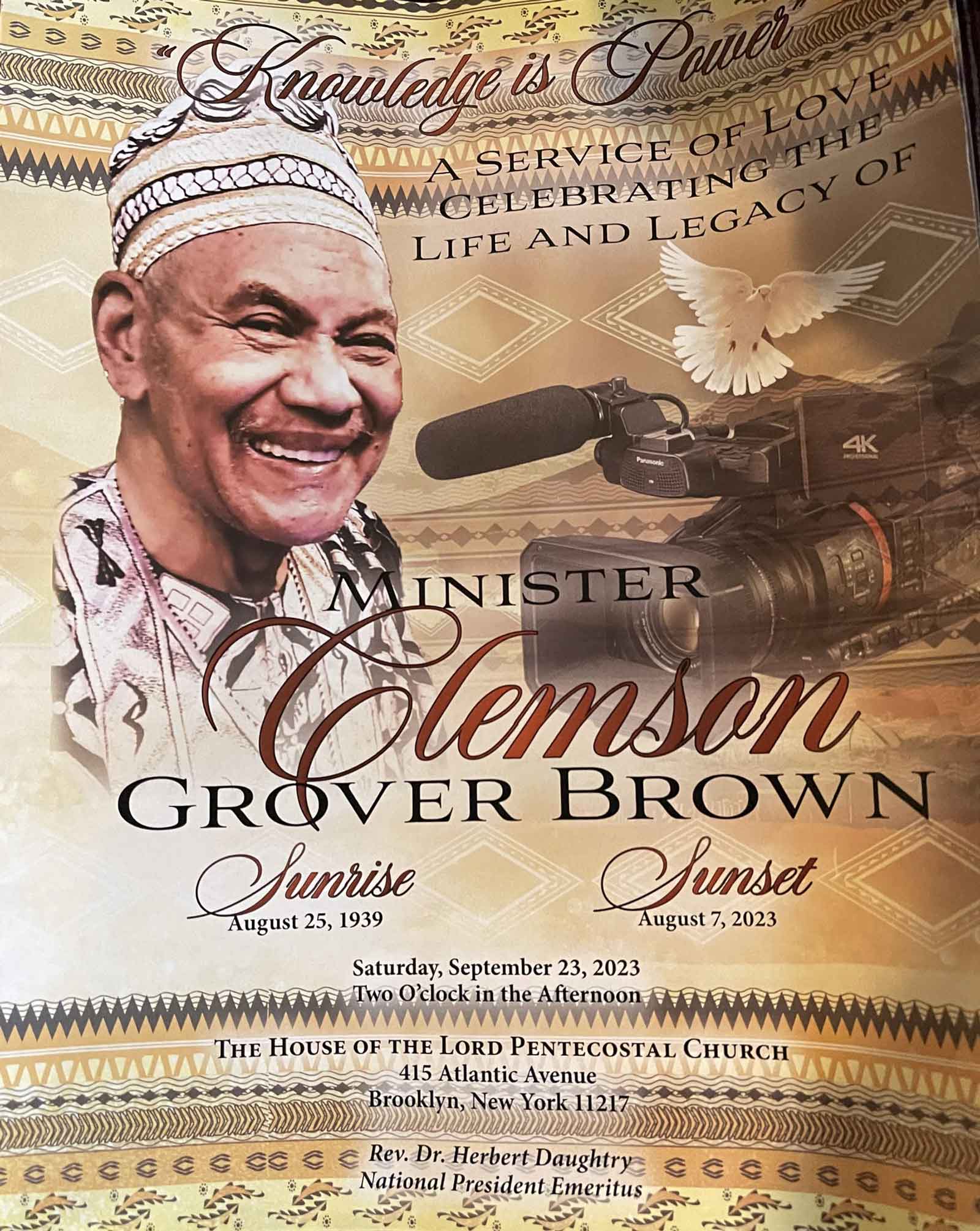

Traveling from Harlem to the Bronx and then to Brooklyn, even under the best of circumstances, can be challenging, particularly by train in a torrent of rain and wind. But two events made the trip necessary: the celebration of the life and legacy of Minister Clemson G. Brown at the House of the Lord Church in Brooklyn and the co-naming of a street for African Jazz Art Society & Studios (AJASS) in the Bronx.

Since both events were on Saturday at practically the same time, coverage had to be shared, which I did with Cinque once I knew it was going to be impossible for me to give each event the time it deserved.

For more than four hours, speakers literally followed the Rev. Dr. Karen Daughtry’s command that a person “is never dead so long as their name is called,” and Clemson’s name resounded with unbroken love and remembrance. Without exception, he was remembered for his proficiency as a documentarian—the basement of his home was a veritable repository of African and African video history and culture. “His camera was a weapon,” said Councilmember Charles Barron, who with his wife, Inez, recounted the precious moments they spent with him.

“It was an honor to be in his presence,” said the Rev. Dr. Derrick Shahem Johnson, pastor of the Black Liberation Church in New York. He observed, as several others did, Clemson’s massive collection of photos, films, and memorabilia during his global treks. Michael Greys, co-founder of 100 Blacks in Law Enforcement, said Clemson “was an army of one, and he presented us with better images of ourselves.”

Two family members, including his nephew Alphonso Martin, Sr. of Unity Church in Woodbridge, Va., praised him for his devotion to the family.

Two family members, including his nephew Alphonso Martin, Sr. of Unity Church in Woodbridge, Va., praised him for his devotion to the family.

Retired NYC Detective Graham Weatherspoon of the Amadou Diallo Foundation recalled first meeting Clemson at Rev. Johnny Ray Youngblood St. Paul’s Church. “One day, I got an urgent call from Clemson in 1995,” he began. “He said I was needed in Poughkeepsie to provide protection during the Tawana Brawley incident. I told him I have a gun and will travel.” During the drive, Weatherspoon said, he got some lessons in Black history firsthand from a master teacher.

Peggy Washington put her memories of Clemson in song, with a special rendition of “May the Work I’ve Done Speak for Me,” and certainly the work Clemson did speak with the same volume and resonance of Washington’s voice.

Passionate reflections flowed from Dr. Leonard Jeffries, who remembered Clemson as his student at the City College of New York City; Elder Cortez Stallings, who got his impressions of Clemson as a classmate of Clemson, Jr.; and Dr. James Smalls; Dr. James McIntosh, of CEMOTAP; and Yaa Asantewaa, whose libations permitted Clemson’s name to soar on the ancestral plane with other notables.

After warmly embracing the Rev. Dr. Herbert Daughtry, who made sure the speakers kept to the allotted time, Clemson Brown Jr. delivered the closing remarks, first by reciting a couple of his father’s poems. One line said, “Let me curse this political arena…and let us make a poem together.” He said his father was an artist who was always trying to do good, “and I accept the challenge he left me.”

Brown left all of us with a monumental challenge to live up to his tireless advocacy for love, peace, and total liberation.

Because of inclement weather, the street naming for tAJASS was postponed to September 30 at 2 p.m. The corner of Longwood and Kelly will have to wait one more week for the honoring. One more week should not hurt when you consider the fact that AJASS was founded in 1956 in the basement office in the home of Cecil and Etelka Brathwaite, two immigrants from Barbados, at 751 Kelly Street. The week’s postponement to honor AJASS will likely make the celebration at the opening of Bill Rainey Park even more magnificent.

Ironically the new date is the same date as when Harlem celebrated the president and cofounder of AJASS in 2017. However, this event will celebrate the legacies of not one man but several important men who have had an important role in our history: like Kwame Brathwaite, Chris Acemandese Hall, Frank Adu Robinson, Jimmy Abu, Bob Gumbs, and a few others.

Nonetheless, there was a pre-gathering of people who came together at the illustrious Bronx Music Heritage Center (1303 Louis Nine Blvd.) despite the AJASS street postponement. They celebrated the legacy of the pioneering group, shared personal stories, and reflected on the evolution of the first Black Arts Movement Organization and the role of the Pioneers of the “Black is Beautiful” movement.

The delay might have been divine messaging that allowed people to attend the memorial service for Clemson Brown. Given Clemson’s wide-ranging peregrinations, there is probably a video of an AJASS event in his bountiful trove.

Source: Amsterdam News