By Chris Kromm

In 1994, at a speech celebrating his inauguration as the first black president of South Africa, Nelson Mandela glanced over to Coretta Scott King and echoed the words of her slain husband’s address at the March on Washington more than 30 years earlier: “Free at last, free at last!”

After his release from prison in 1990 and rise to the presidency, Mandela would often pay homage to Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern civil rights movement, which he said were an inspiration to him and other anti-apartheid activists in South Africa.

But the influence went both ways: Mandela and the anti-apartheid struggle were also an inspiration to civil rights activists in the South, especially African-American organizers who, in the course of the 1960s, sought to link their fight against Jim Crow with liberation movements unfolding in Africa and around the world.

Several people were key to connecting the movements in South Africa and the U.S. South. George Houser, a white minister and early supporter of U.S. civil rights, helped found the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in 1942, and along with colleague Bayard Rustin organized one of the first “freedom rides” in the South in 1947. A child of Methodist missionaries, Houser had an internationalist perspective that led him to found what would become the American Committee on Africa (ACOA) in 1952 to support African liberation movements, especially in South Africa.

“We always conceived our work as part and parcel of the civil rights struggle,” Houser would later say. “The struggle in Africa was to us, as Americans, an extension of the battle on the home front.”

In 1960, the Sharpeville massacre — where South African police opened fire on black demonstrators in a Transvaal township, killing 69 people — helped propel apartheid into the news headlines, inspiring more U.S. civil rights leaders to take action. In 1962, Dr. King and Albert Luthuli — a leader of the African National Congress when Nelson Mandela became active — issued an Appeal for Action Against Apartheid with ACOA signed by 150 world leaders.

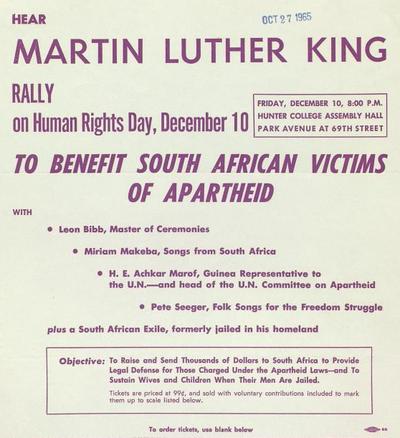

In December 1965, a year after Mandela had been jailed for life, Dr. King was asked to speak at a benefit for the American Committee on Africa, a New York-based group founded in 1953 to support African independence movements. King’s speech began:

Africa has been depicted for more than [a] century as the home of black cannibals and ignorant primitives … Africa does have spectacular savages and brutes today, but they are not black. They are the sophisticated white rulers of South Africa who profess to be cultured, religious and civilized, but whose conduct and philosophy stamp them unmistakeably as modern-day barbarians.

Noting that “the shame of our nation is that it is objectively an ally of this monstrous government,” King called for a “massive international boycott” involving the U.S. and other industrialized nations.

King was never able to witness the situation in South Africa first-hand: According to reporter Jason Strazioso, King applied for a visa after being invited by student and church groups to visit, but the apartheid government denied it.

The African connection

U.S. civil rights activists were learning about Africa through other channels. One event frequently mentioned in memoirs by activists is a 1964 trip organized by entertainer and progressive leader Harry Belafonte, who led 18 activists in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee on a three-week tour to meet African independence leaders.

The visit had a big impact on SNCC organizers like John Lewis, who would return a year later and report to his SNCC co-workers [pdf]: “I am convinced more than ever before that the social, economic, and political destiny of the black people in America is inseparable from that of our brothers in Africa.”

Even as Vietnam dominated the public debate, the growing identification among civil rights activists with Africa helped keep apartheid on the movement’s agenda in the 1960s. In March 1965, SNCC and CORE joined Students for a Democratic Society protest at Chase Manhattan Bank’s New York headquarters for their loans to the South African regime; in 1969, Chase and nine other banks cancelled a $40 million loan to the government after church groups threatened to dump their Chase accounts.

In 1967, SNCC would submit a paper to the United Nations identifying with the South African struggle, even noting the parallels between the jails that held Mandela and King:

We can understand South Africa because we have seen the inside of the jails of Mississippi and Alabama and have been herded behind barbed wire enclosures, attacked by police dogs, and set upon with electric prods — the American equivalent of the sjambok. There is no difference between the sting of being called a “kaffir” in South Africa and a “nigger” in the U.S.A. The cells of Robin Island and Birmingham jail look the same on the inside. As the vanguard of the struggle against racism in America, SNCC is not unfamiliar with the problems of southern Africa.

U.S. activists may have also drawn concrete organizing ideas from South Africa. Part of the inspiration for the “Freedom Vote” organized by Mississippi activists in 1963 — mock elections that showed how African-Americans would vote if given real access to the ballot — appears to have come from Allard Lowenstein’s travels to South Africa, where he observed blacks using similar tactics to protest voting exclusions under apartheid. While Lowenstein’s exact role in giving birth to the Mississippi “freedom vote” idea is contested, historians seem to agree his South Africa experience contributed in some way.

This rising consciousness about Africa would later find expression in the 1970s in groups like the African Liberation Support Committee and the TransAfrica Forum, which is credited with launching the first sit-ins to demand U.S. action in South Africa, precipitating the successful sanctions movement of the 1980s.

Common foes

The freedom movements in the U.S. South and South Africa had another connection: They shared many of the same antagonists in the U.S. government.

The most visible common foes were Southern politicians like North Carolina Sen. Jesse Helms. Helms bitterly opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which he called “the single most dangerous piece of legislation ever introduced in the Congress.” He was also a staunch foe of King, whom he castigated as a “communist” who used “nonviolence as a provocative act to disturb the peace of the state and to trigger, in many cases, overreaction by authorities.” When the Senate moved to create a holiday honoring Dr. King, Helms fillibustered.

Helms’ animosity to King and civil rights was uncannily similar to his opposition to Mandela and the anti-apartheid struggle. In the U.S. Senate’s 1985 deliberations over sanctions against South Africa, Helms moved to block debate on the bill but was outnumbered. After sanctions eventually passed, Helms was defiant, arguing that “[t]he thrust of this legislation is to bring about violent, revolutionary change, and after that, tyranny.”

Helms specifically attacked Nelson Mandela as a “communist,” saying, “Before we get his halo in place too securely, let’s examine this guy.” When Mandela came to address Congress after being freed in 1990, Helms reportedly didn’t attend; when Mandela came again in 1994, Helms turned his back.

But Helms was just the most visible face of a broader Cold War perspective in the U.S. establishment that viewed both the civil rights and anti-apartheid movements with at best suspicion, and often as enemies of the state. The U.S. government feared the civil right’s movement’s ties to leftist groups, and an internal Department of Defense memo on SNCC from 1967 shows they took an especially deep interest in the travels of SNCC activists to South Africa and other countries and its impact on their political outlook.

U.S. opposition to Mandela and the anti-apartheid movement was similarly justified on the grounds of Cold War politics: Today, the U.S. State Department openly acknowledges that support for South Africa’s apartheid government was defended largely because the regime was viewed as a “bulwark against communism.”

But in both the U.S. South and South Africa, the combination of organized resistance and international solidarity was able overcome legalized segregation, if not fulfill the larger ambitions of both movements for broad social change. In his 1990 visit to Atlanta, Mandela invoked the legacy of both freedom movements in calling for a continuation of the struggle for human rights:

We are … conscious that here in the southern part of the country, you have experienced the degradation of racial segregation. … Let freedom ring. Let us all acclaim now, ‘Let freedom ring in South Africa. Let freedom ring wherever the people’s rights are trampled upon.’

(To comment on or to share this story, click here. For two interesting accounts of the U.S. anti-apartheid movement and its connections to U.S. civil rights, see the book “No Easy Victories” and the film series “Have You Heard from Johannesburg,” the fifth episode of which is titled “From Selma to Soweto.”)