By Dani McClain

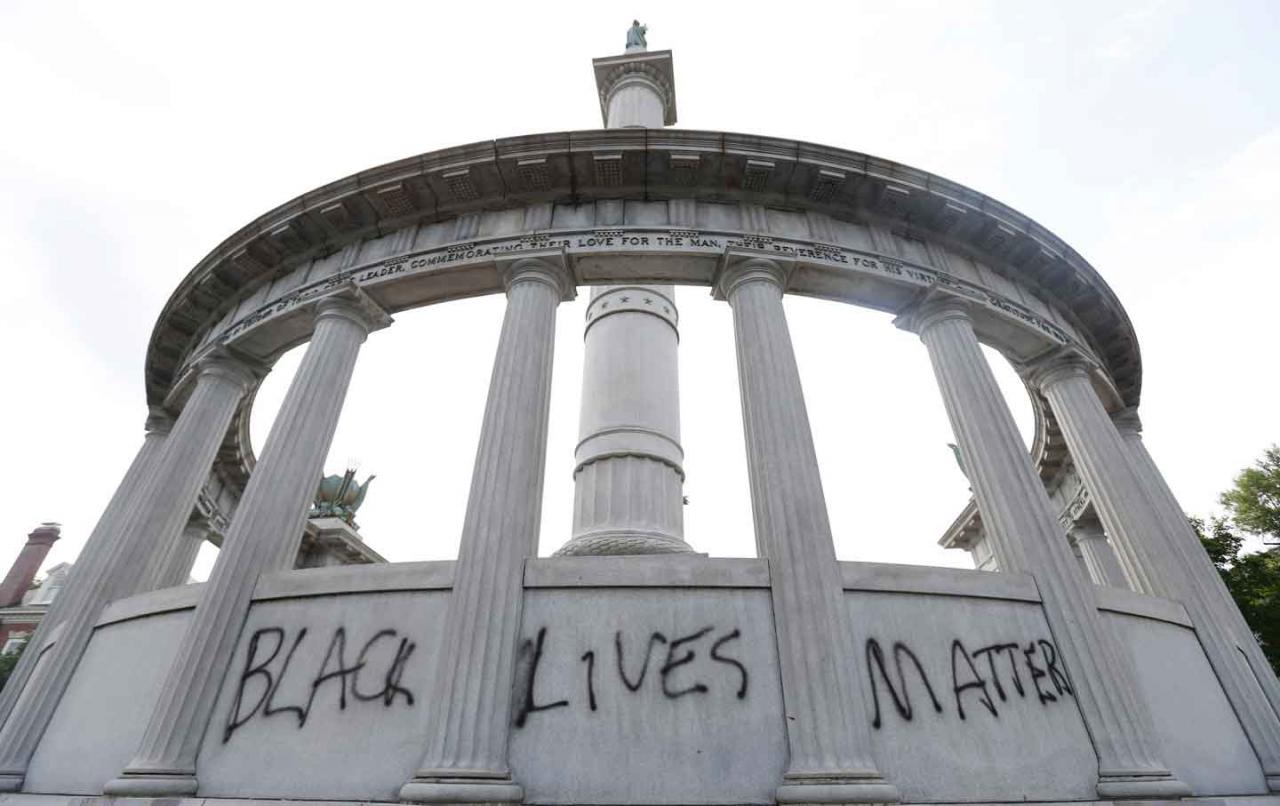

A monument to former Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Richmond, Virginia. (AP Photo / Steve Helber)

In March 2012, nearly a month after George Zimmerman killed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida, hundreds of high-school students in Miami-Dade and Broward counties staged walkouts to protest the fact that Zimmerman hadn’t been arrested on any charges. A group of current and former Florida college activists knew that they had to do something too. During a series of conference calls, Umi Selah (then known as Phillip Agnew) and others in the group planned a 40-mile march from Daytona Beach to the headquarters of the Sanford Police Department—40 miles symbolizing the 40 days that Zimmerman had remained free. On Good Friday, 50 people set off for Sanford. The march culminated in a five-hour blockade of the Sanford PD’s doors on Easter Monday. The marchers demanded Zimmerman’s arrest and the police chief’s firing. Within two days, both demands had been met.

A little over a year later, a jury found Zimmerman not guilty on charges of second-degree murder or manslaughter. Undeterred by the legal setback, the activists—calling themselves the Dream Defenders—showed up in Tallahassee and occupied the Florida statehouse for four weeks in an effort to push Republican Governor Rick Scott to call a special legislative session to review the state’s “stand your ground” law, racial profiling, and school push-out policies, all of which the organization linked to Martin’s death. Fueled in part by participants sharing updates on Twitter, the occupation became a national story, and Selah fielded a flood of requests from media and progressive organizations. Some wanted to give an award to the Dream Defenders; others wanted to add Selah to lists proclaiming the arrival of a new generation of civil-rights heroes. (One writer said he embodied the spirit of Nelson Mandela.) Others wanted his perspective on the burgeoning racial-justice movement. After a while, Selah wanted none of it.

The breaking point came when a major news outlet profiled him without first conducting an interview. The result, he says, was an account that credited him with successes in social-justice movements he wasn’t even involved in. “If I was a person in the [immigrants’-rights] movement, I would look at this article and think, ‘Who the hell is this dude?’” he told me. “I really panicked. I imagined somebody saying, ‘Why is this dude telling Time magazine that he’s been in the forefront of these movements, and we’ve never seen him here?’”

Selah’s response was to pull himself out of the spotlight. He started declining media requests and posting less often to social media. When he did accept an invitation to speak, his goals were to disavow any hero label thrust on him by others and to demystify the Dream Defenders’ work.

Selah is an organizer, not a media personality, and so the trade-off made sense for him. But for others, that might not be the case. Twitter personality and trailing Baltimore mayoral candidate DeRay Mckesson was described in a recent New York Times profile as “the best-known face of the Black Lives Matter movement” and BLM’s “biggest star.” Now followed by more than 300,000 Twitter users, Mckesson began building his following by live-tweeting the protests in Ferguson in August 2014 after driving there from Minneapolis, where he lived at the time. More than a million mentions and retweets on the social-networking platform made him the protagonist of the Times magazine’s cover story on Black Lives Matter and earned him a spot on Fortune’s World’s Greatest Leaders list. But is he an organizer? The historian Barbara Ransby, author of Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement, says she defines organizing as “bringing people together for sustained, coordinated, strategic action for change.” Mckesson, who wisely calls himself a “protester,” is doing something else entirely. The problem is that too many of us don’t know to look for the difference.

* * *

Today’s racial-justice movement demands an end to the disproportionate killing of black people by law-enforcement officials and vigilantes, and seeks to root out white supremacy wherever it lives. Social media has allowed its members to share documentary evidence of police abuse, spread activist messages, and forge a collective meaning out of heartrending news. At certain key moments, Twitter in particular has reflected and reinforced the power of this movement. On November 24, 2014, when the St. Louis County prosecutor announced that a grand jury had decided not to bring charges against the officer who killed an unarmed Michael Brown, Twitter users fired off 3.4 million tweets regarding the police killings of black people and racial-justice organizing, with the vast majority coming from movement supporters and news outlets, according to a recent report by American University’s Center for Media and Social Impact. Weeks later, when the police officer who choked Eric Garner to death in New York City was also not indicted, 4.4 million tweets over a period of seven days kept the nation’s attention focused on the fight for police accountability. Hashtags like #BlackLivesMatter, #Ferguson, #HandsUpDontShoot and #IfTheyGunnedMeDown gave users—including those not yet involved in activism—a way to contribute to conversations they cared about.

But while social media turns the microphone over to activists and organizers who are often far from the center of the media’s attention, its power doesn’t come without pitfalls. In August, a nasty Twitter fight erupted after Mckesson initiated a meeting with Bernie Sanders’s campaign. Writer and activist dream hampton posted a tweet that read: “While a meeting with @deray might be a blast, I would expect @BernieSanders to meet with actual BLM folks, those who forced this platform.” At the heart of the criticism was the claim that Mckesson was not in a position to speak to a presidential candidate on behalf of the Black Lives Matter network—an organization with chapters that grew out of the hashtag created and popularized by Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi, and Patrisse Khan-Cullors.

“We’re building the bicycle while riding it and being shot at. ” —Ash-Lee Woodard Henderson, Project South

That distinction was lost on many of Mckesson’s followers. For them, he was a reliable voice: at times a source of first-person accounts of the protests, at others a consistent and inspiring source of commentary on the issues they cared about. The difference between an organization called Black Lives Matter and a movement that had come to be known by the same name was, to many, negligible and a distraction from the real story: a young black man who was saying the right things on Twitter would be meeting with a presidential candidate.

But for someone like hampton or Selah, the stakes were much higher. “The people who the liberal media and social media have elevated to the position of national leader or spokesperson do not share the values of the movement,” Selah told me. “The ideas that they put forth, the platforms that they put forth, are neoliberal and do not come from a rooting in movement, don’t come from a liberation framework, from an abolition framework.” (Mckesson declined repeated requests for an interview for this story.)

So what are the values of the movement? Who is spreading them—and how? Charlene Carruthers, national director of Black Youth Project 100, has been engaged with those questions for more than a decade. While an undergraduate at Illinois Wesleyan University, she was active in the Black Student Union. She worked on campaigns in support of young black candidates while getting her master’s degree in social work in St. Louis. After she graduated, she joined the staff at an affiliate of the Industrial Areas Foundation in Virginia and managed online campaigns at the civil-rights organization ColorofChange. (Full disclosure: She and I were colleagues there.)

Since July 2013, when Zimmerman was acquitted, Carruthers has helped build BYP 100, a youth-led organization made up of people between the ages of 18 and 35. BYP 100 has developed a democratic decision-making process and operates from what Carruthers calls a “young black queer feminist” perspective. The group now has an estimated 300 members nationwide and chapters in Chicago, New Orleans, Detroit, Oakland, and Washington, DC. Its work in Chicago has drawn the most attention: In response to the police killing of 17-year-old Laquan McDonald and the killing of 22-year-old Rekia Boyd by an off-duty officer, BYP 100 organized protests and marches that played a key role in the firing of Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy in late 2015. A recent Chicago magazine article declared the chapter “the most vocal and arguably most effective activist group in town.” How did they get there? Carruthers explains: “We recruit. We do trainings. We do campaign work. That’s the slow, hard work of organizing. Building a base is what we do.”

Writing in Truthout, organizer Ejeris Dixon, who has worked with the New York City Anti-Violence Project and the Audre Lorde Project, describes base-building as, at heart, relationship-building: “a series of activities designed to introduce, engage, and keep people involved in our movements. That means meeting individuals where they are and building forward from that place—the barbershop, the salon, the laundromat, the doorway—where we come together as people and have a conversation.” The Movement for Black Lives policy table, which grew out of a national gathering of activists at Cleveland State University last summer, recently set out to do just that. In January, the policy table announced the start of a six-month process to develop a national agenda. Ash-Lee Woodard Henderson, a regional organizer with Project South, is a participant. She says she feels the pressure of developing a vision and creating infrastructure while responding to the seemingly endless killings of black people by police: “We’re building the bicycle while riding it and being shot at.”

Henderson’s background, like Carruthers’s, shows deep connections to earlier iterations of the black-liberation movement in the United States. “My mom is an original Black Panther Party member, and my father was very big in the Black Arts Movement in Tennessee and also in the black radio scene,” Henderson says. When a 66-year-old black man named Wadie Suttles died in custody at the Chattanooga jail in 1983, her father took the bold step of naming the police officer suspected of the fatal beating on the air. In 2004, Henderson met veterans of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference when she took a monthlong bus ride with other young activists to register voters and commemorate Freedom Summer.

Among the current organizers, evidence of such long-standing commitment to racial justice is common, notes Barbara Ransby. Many leaders are taking the skills developed in labor or prison or community organizing and applying them to new collaborations. “Oftentimes we don’t do that genealogy, and a new organization feels like it came out of the blue,” she said. “There were new formations, but they were not newly formed organizers.”

* * *

“The work we have to do doesn’t necessarily lend itself to 140 characters.” —Rachel Gilmer, Dream Defenders

What is new, at least for many, is the space for explicitly black organizing undertaken by activists tied to black communities. Makani Themba, a longtime organizer and founding director of the Praxis Project, explains that in the 1960s, the leaders of the movement were the heads of black institutions with sizable bases—think Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Ella Baker, Stokely Carmichael. That changed in ’70s and ’80s, as black leadership came to mean “the most deeply penetrated black person in white or mainstream institutions,” Themba adds. As civil-rights organizations began to depend more on corporate contributions than member donations, and as Reagan-era cuts decimated organizations serving the black poor, black activists who wanted organizing and advocacy jobs turned to the institutions that had the resources to pay and retain them—often unions and economic-justice organizations that operated outside any explicitly black cultural context.

That pattern has shifted in recent years. The phrase “unapologetically black” appears on T-shirts and hoodies worn by movement activists, and a dedication to using messages appealing to black audiences dominates today’s approach to racial-justice organizing. New groups like BYP 100, the Dream Defenders, and Black Lives Matter have blossomed in the wake of Zimmerman’s acquittal. Denise Perry directs Black Organizing for Leadership & Dignity, whose stated mission is to “help rebuild Black social justice infrastructure…and re-center Black leadership in the US social justice movement.” BOLD launched in 2011 and graduated its first class of trainees the following year. Perry says that the focus on black organizing was new for a majority of participants. “Many of them were organizing in multiracial, multiethnic organizations. That work is important; we’re not going to win on our own. But the space to have conversations about what we need to work on was new for 98 percent of the people in the room.”

* * *

After the Dream Defenders’ successful occupation of the Florida statehouse in 2013, its members were tempted to focus on actions that would satisfy a Twitter following that had jumped from about 4,000 to more than 30,000 in a month’s time. But the work of organizing “has to be done,” says Rachel Gilmer, 28, who joined the group last summer, “and it doesn’t necessarily lend itself to 140 characters that are going to get retweeted thousands of times.

In the end, the commitment to building local campaigns won out over the lure of high visibility. The organization, which has eight chapters in Florida, is now in the midst of a yearlong effort to determine its long-term strategy, regardless of the ebbs and flows created by social-media buzz. Last fall, the group put a three-month moratorium on social media, which strengthened relationships and built trust among colleagues, Gilmer says. “It was an opportunity for us to take a break from all the noise in order to get back connected with one another.”

It also forced a reality check about relationships in the movement. “We’re like ‘Hey, fam!’ [online], but people don’t really know each other,” Gilmer says. “There’s no substitute for human interaction.”

Twitter feeds constantly updated with smart observations about the latest cause for outrage are a lot more visible than the painstaking meetings that precede a transit-system shutdown, a citywide protest, or a collaboratively written 40-page policy agenda. But understanding the distinction between organizers and amplifiers matters; otherwise, we’ll overrate those who excel at amplifying the passion of a movement and undervalue the organizers, who make concrete change happen. Or as Henderson puts it: “The press doesn’t tell me who the leaders of particular movements are—communities do.”