Vice President Biden joined John Lewis and others at the annual pilgrimage to Selma in 2013. (Dave Martin/AP) When civil-rights activists converge on Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge next Saturday, they’ll have a bigger goal than simply commemorating the 50th anniversary of “Bloody Sunday.” The 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, helped secure the passage of the Voting Rights Act. This year, dozens of politicians will be there to join the celebration, and activists hope to persuade them that a better way to honor Selma’s legacy is to extend the legal protections it secured.

Vice President Biden joined John Lewis and others at the annual pilgrimage to Selma in 2013. (Dave Martin/AP) When civil-rights activists converge on Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge next Saturday, they’ll have a bigger goal than simply commemorating the 50th anniversary of “Bloody Sunday.” The 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, helped secure the passage of the Voting Rights Act. This year, dozens of politicians will be there to join the celebration, and activists hope to persuade them that a better way to honor Selma’s legacy is to extend the legal protections it secured.

Thanks to the eponymous Oscar-nominated film, there has been no shortage of remembrances of Selma. This year’s pilgrimage, organized by the Faith and Politics Institute, will command more attention than others have in recent years. Not only will President Obama make the trip, but so will his Republican predecessor, George W. Bush, who signed the last renewal of the landmark law in 2006. African American leaders view the bipartisan commemoration as a crucial moment to marshal support and pressure Republican leaders for new voting-rights legislation in Congress.

In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down a key tenet of the Voting Rights Act. In a 5-4 opinion that fell along ideological lines, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that the formula used to determine which parts of the country would need federal approval, or “preclearance,” to change their voting procedures was outdated. The court instructed Congress to write a new formula that “speaks to current conditions,” but nearly two years later, neither the House nor the Senate has held a vote.

Democrats assailed the ruling, warning that it would give Republican state legislatures in the South carte blanche to move ahead with voter-identification laws and other restrictions disproportionately affecting historically underrepresented populations. Within two months of the decision, North Carolina enacted an expansive voter ID law, and other states followed suit ahead of the 2014 election. “We’re moving backwards in an area where we should be making voting easier rather than harder,” Representative John Conyers said by phone last week. “We’re going in the wrong direction.” He pointed to lower turnout among African Americans in southern states during 2014 as evidence that the Supreme Court ruling was already having an impact. “That’s what we’re trying to end,” he told me. (Black voter turnout has consistently dropped in non-presidential years, however.) Cornell Brooks, the NAACP president, has gone even further, calling the efforts to restrict voting in Republican-led states “a Machiavellian frenzy of disenfranchisement.”

“We’re moving backwards in an area where we should be making voting easier rather than harder. We’re going in the wrong direction.”For a time in the last Congress, advocates had at least some hope that the Republican House leadership would take up a bipartisan proposal from Conyers, a Michigan Democrat, and Republican Jim Sensenbrenner of Wisconsin. Then-Majority Leader Eric Cantor made the pilgrimage to Selma in 2013 and then held discussions on the bill with lawmakers and civil-rights groups, including the NAACP. But Cantor lost his primary last June, and Republicans replaced him on their leadership team with Representative Steve Scalise, a Louisiana conservative now best known outside Washington for speaking, during his tenure as a state legislator, to a white-nationalist group affiliated with David Duke.

Speaker John Boehner has since deferred to the chairman of the Judiciary Committee, Bob Goodlatte of Virginia. In January, Goodlattetold reporters it was not “necessary” to update the law following the Supreme Court decision. “Things are still going uphill,” Conyers said. Representative James Clyburn of South Carolina, a member of the Democratic leadership who is working on the issue, said Scalise had told him that passing the bill “is going to be difficult.” And that’s just the House. In the Senate, the new Republican majority has shown little interest thus far in tackling voting rights.

Compounding the challenge for advocates is that the Sensenbrenner-Conyers proposal is a compromise in itself, designed to attract Republican support. (It has seven GOP co-sponsors at the moment.) As such, some Democrats don’t believe it goes far enough. The chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus, Representative G.K. Butterfield, told me that supporting the legislation gave him “heartburn” because the new formula would exclude states like North Carolina, South Carolina, and even Alabama, home to Selma and Montgomery. It would also exempt voter ID laws—a top target of Democrats—from counting as a violation that could subject a state to federal preclearance. “I was willing, in the spirit of compromise, to support the amendment in hopes that we could get it passed, under the theory that some change is better than no change,” Butterfield said. “But it looks like the bill is not going to get an up-or-down vote in the foreseeable future.”

The long odds facing even this watered-down voting-rights legislation have spurred some Democrats to pursue a parallel, if even more unlikely, path: a constitutional amendment guaranteeing the right to vote. Following a push from Donna Brazile, a longtime Democratic operative who is now a top party official, the Democratic National Committee approved a resolution backing a change to the Constitution, which would go beyond what is now in the post-Civil War amendments. “We think it’s not an either/or, it’s both,” Brazile said of the two-pronged strategy. Every two years, she argued, the party spends millions of dollars to pursue legal challenges against states that are enacting restrictive voter-ID laws, curtailing early voting, or otherwise reducing ballot access. “We’re still fighting a rear-guard battle,” she said. Yet other advocates are skeptical of the constitutional-amendment tactic, arguing that Democrats should focus their attention on securing an immediate fix to the 1965 law rather than starting a fight that would certainly take a decade or more to win.

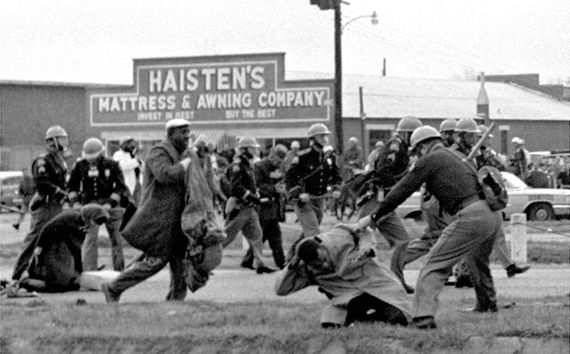

Police swing billy clubs at Selma marchers in 1965. (AP file)That’s where this weekend’s Selma pilgrimage comes in. Although Obama walked across the Pettus Bridge alongside then-Senator Hillary Clinton in 2007, he will be the first sitting president in 15 years to speak at the commemoration. Black leaders are expecting Obama to use the Saturday address not only to honor John Lewis and others who risked their lives to march in 1965, but also to make a forceful case for new voting-rights legislation in 2015. His audience will include, in addition to the second President Bush, a record 95 members of Congress alongside a number of potential presidential candidates. Republican attendees will include Senators Rob Portman, Tim Scott, and Jeff Sessions, as well as a handful of House members. Butterfield said he hoped the anniversary would lead to “an awakening” within the GOP on voting rights. “This is indeed the best window of time. Right now,” he said.

Police swing billy clubs at Selma marchers in 1965. (AP file)That’s where this weekend’s Selma pilgrimage comes in. Although Obama walked across the Pettus Bridge alongside then-Senator Hillary Clinton in 2007, he will be the first sitting president in 15 years to speak at the commemoration. Black leaders are expecting Obama to use the Saturday address not only to honor John Lewis and others who risked their lives to march in 1965, but also to make a forceful case for new voting-rights legislation in 2015. His audience will include, in addition to the second President Bush, a record 95 members of Congress alongside a number of potential presidential candidates. Republican attendees will include Senators Rob Portman, Tim Scott, and Jeff Sessions, as well as a handful of House members. Butterfield said he hoped the anniversary would lead to “an awakening” within the GOP on voting rights. “This is indeed the best window of time. Right now,” he said.

“It is perversely ironic to commemorate the past without demonstrating the courage of that past in the present.”That might be wishful thinking, and it raises the possibility that the pilgrimage will turn overtly political, against the wishes of the non-partisan organizer, the Faith and Politics Institute. The goal of the pilgrimage is to create “a safe place for members of Congress, regardless of party,” said Robert Traynham, the institute’s spokesman. “We are not talking about policy. We are not talking about any piece of legislation,” he said. “That’s not our role.” Yet as advocates are quick to note, it’s hard to argue that advocacy would be out of place at an event honoring one of the nation’s most famous political protests.

“It is perversely ironic to commemorate the past without demonstrating the courage of that past in the present,” the NAACP’s Brooks told me last week. “In other words, we can’t really give gold medals to those who marched from Selma to Montgomery without giving a committee vote to the legislation that protects the right to vote today.”

“It’s not a matter of ancient history,” he continued. “It’s a matter of history echoing very much in the present.”