By Karen Jordan

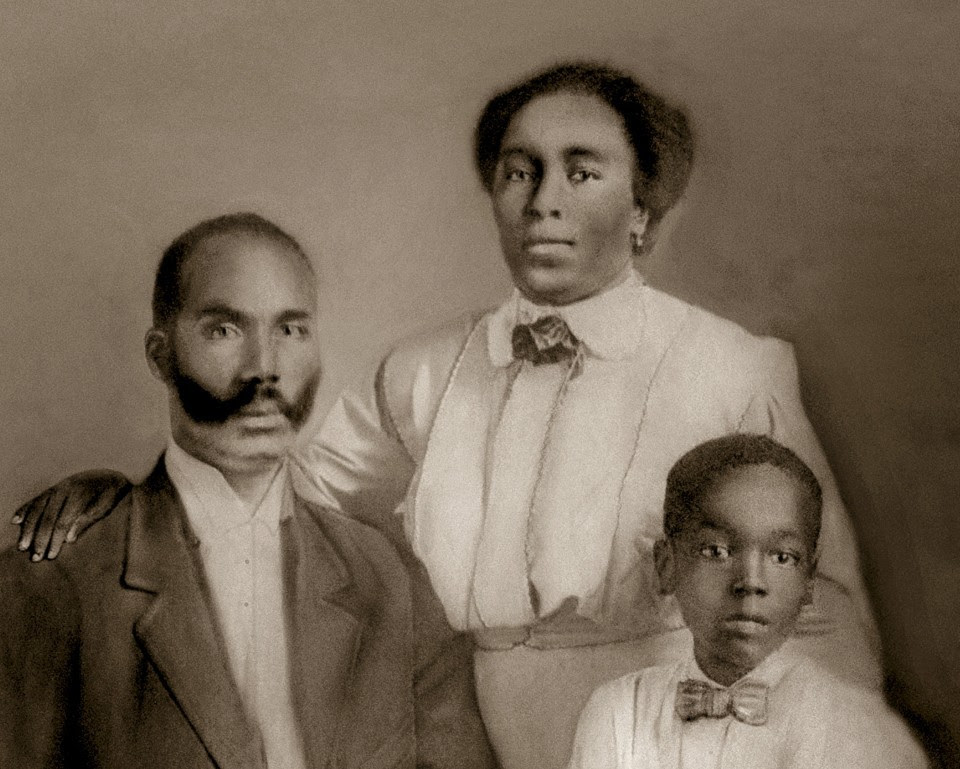

John Henry Jordan, the first black doctor in Coweta County, Georgia, with his wife, Mollie, and his son, Edward Courtesy of Karen Jordan

Around 1906, a young boy in Atlanta was stricken with a condition that cut off the circulation in his legs. His family feared it was life-threatening.

His father, an African American minister named Briny Jordan, took him to the closest doctor he could find in the city. The doctor was white, so Briny had reservations. But out of necessity, he went.

A portrait of John Henry Jordan

(Courtesy of Karen Jordan)

After examining Briny’s son, the doctor said he’d have to amputate one of the boy’s legs. Briny may not have been a learned man, but he was no dummy. He aimed to get a second opinion, and he knew just which doctor to call on: his brother.

John Henry Jordan, Briny’s brother, was the first African American doctor in Coweta County, Georgia. He’d graduated at the top of his class from medical school at a time when most former slaves had never seen a doctor who looked like them. Georgia had 65 black physicians in 1905, according to The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience In Georgia, by Donald Lee Grant. These men not only endured racism, but often weren’t trusted even by other African Americans, who believed they were poorly trained compared to their white counterparts.

More than a century later, African American doctors still face barriers when it comes to educational opportunities and advancement in their careers. In 2015, they made up around 6 percent of practicing physicians in America—an increase of only a few percentage points since the middle of the 20th century.

The story of African American doctors since John Henry Jordan’s days has been one of both incredible achievement and deep-seated discrimination. It’s also the story of my family. John Henry Jordan is my great-grandfather. Harold Jordan, my father, was the first African American medical resident on record at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. He was regularly mistaken for a janitor and told where to empty the trash.

In Atlanta, Briny grabbed his son, hitched up his mule and wagon, and rode 38 miles to Coweta County. John examined his nephew and told Briny not to worry. There was no need for the boy’s leg to be amputated.

* * *

John and Briny were born in Troup County, Georgia, to former slaves turned sharecroppers. Their father intended the brothers to be sharecroppers, as well. But when John was around 12, the first “colored doctor,” as an 1881 edition of the LaGrange Reporter newspaper announced, moved to town. The man, Edward Ramsey, was a native son whose father, a “mulatto” man, had sent him to Nashville to medical school.

John had never seen a doctor who looked like him. Motivated by a longing to help his community, he decided to become a doctor, too.

Unlike Ramsey, however, John had no means. Ramsey’s father had been a landowner who had 100 acres in Hogansville, Georgia, when he died, in 1896. John’s father tried to forbid John from continuing his education beyond elementary school. What African American man would conceive of such a cockamamie thing?

But John would not be dissuaded. He used the trail Ramsey had blazed: After getting a degree from Clark College in Atlanta, John was eventually accepted at Ramsey’s alma mater, Meharry Medical College, known then as the Meharry Medical Department of Central Tennessee College. The students were taught primarily by white doctors, a former Confederate surgeon among them, some of whom sacrificed their reputations to teach the former slaves and children of slaves.

In John’s third and final year, Meharry decided to change its graduation requirements from three years to four, in order to be competitive with medical colleges nationwide. It took John a year to save enough money to continue, but he made it. In 1896, he became a doctor.

* * *

Starting out as an African American physician at the end of the 19th century was a daunting task, to say the least. Upon entering the profession, white doctors would join the American Medical Association, or AMA, an organization founded in 1847 that outlined standards for medical education and focused on improving public health. Doctors had to be members of the AMA to practice at hospitals. While the AMA claimed not to discriminate, it left membership decisions up to its local chapters, which made an African American doctor hard pressed to find a chapter that would accept him, particularly in the South.

There were other obstacles, too. African American physicians often were unable to get specialized training. They had to compete for African American patients who could actually pay. Limitations like these fueled what Thomas Ward, the author of Deluxe Jim Crow, considers a “self-fulfilling prophecy”: “Black physicians were usually excluded from being able to practice at any of the hospitals in the South,” he says. “So if you’ve got a doctor who can’t practice at the hospital, and you think he’s inferior anyway, that seems to prove he’s inferior.”

In response to being barred from the AMA, African American doctors—along with dentists and pharmacists—founded the National Medical Association, or NMA, in 1895. The NMA is still thriving today and focuses on promoting the interests of African American doctors as well as supporting healthcare for African Americans and those from underserved communities.

African American doctors also began opening their own hospitals in their homes. On the cusp of the 20th century, these small hospitals were often rudimentary, with some doctors, starting them with just a couple of beds, according to Vanessa Northington Gamble, the author of Making a Place For Ourselves. One of the most well-known ones, Provident Hospital in Chicago, earned a reputation with its nurse training school. Its founder, Daniel Hale Williams, was an African American surgeon credited with performing one of the first successful open heart surgeries.

By the early 1900s, John Jordan had converted a small house next to his own into a hospital for African Americans in Coweta County. He had settled there after briefly practicing medicine in his hometown of Hogansville. John found Coweta County more fruitful and found a wife along the way: Mollie Ramsey, the daughter of the man who first inspired him to go into medicine.

John’s hospital stayed open for some time, even after his death, in 1912, from a car accident on his way to a house call.

John Henry Jordan’s house, next to the hospital he built

(Courtesy of S.L. Fowler)

* * *

In the first half of the 20th century, the progress African American doctors had made was stymied. The Flexner Report, a study of medical education in North America issued in 1910, dealt a devastating blow by imposing a new standard on medical colleges the majority of African American schools could not meet. It required all medical schools to be affiliated with a university as well as a hospital, and stressed the importance of clinical training and having a full-time faculty.

At least four African American medical schools closed, according to Duke University’s Medical Center Library. Howard University College of Medicine and Meharry Medical College were the exceptions. How would black doctors be educated now if they had so few schools to choose from? The report also stated African American doctors should focus more on public health.

As the second half of the 20th century unfolded, things started to move forward again. Southern medical schools began to desegregate in 1948, and new doors opened for African American doctors.

More also had opportunities to work in integrated settings. The latter half of the 20th century saw the introduction of two new African American medical schools: Charles Drew University of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles and Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta.

But issues with how African American doctors are perceived persisted, and remain a problem today. “When a black person walks in, whether this person is really a physician, they walk into a hospital not being perceived as a physician, but as a member of the housekeeping staff,” Gamble says. “So there are those biases I think black doctors still face, not the exclusion of the past but implicit biases. … Some people believe black physicians are there because of affirmative action, and they’re not as qualified as a white physician.”

In 2008, the American Medical Association issued an official apology, acknowledging its “past history of racial inequality toward African-American physicians.” Historians say for change now to occur, ways must be found to boost the number of African American men and women attending medical school.

The cost of medical-school tuition is one obstacle. And with increased career options after integration, many African American students who could go on to medical school are choosing other options instead. “When I was going to medical school,” Gamble says, “there were some people who were saying, ‘I’m going to Wharton to get an MBA. I can be out in two years.’”

“It’s a pipeline issue,” says Susan Reverby, a historian of medicine and a Wellesley College professor. “How do you start making it possible for black children to imagine this is something they can do?”

My family has shown that having a role model can be key. Like John followed in Edward Ramsey’s footsteps, my father, Harold, followed in John’s. He graduated from Meharry, John’s alma mater, in 1962, and went on to chair a department and teach at the school for 30 years. Now, generations of African American doctors he taught are practicing medicine nationwide.