By Valerie Volcovici

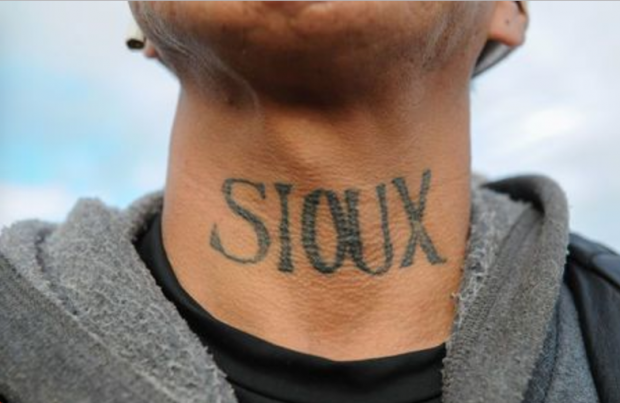

A man from the Lakota Sioux tribe with a Native American tattoo on his neck poses for a photograph during a protest against plans to pass the Dakota Access pipeline near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, near Cannon Ball, North Dakota, U.S. November 16, 2016. REUTERS/Stephanie Keith

Above Photo: A man from the Lakota Sioux tribe with a Native American tattoo on his neck poses for a photograph during a protest against plans to pass the Dakota Access pipeline near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, near Cannon Ball, North Dakota, U.S. November 16, 2016. REUTERS/Stephanie Keith

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – Native American reservations cover just 2 percent of the United States, but they may contain about a fifth of the nation’s oil and gas, along with vast coal reserves.

Now, a group of advisors to President-elect Donald Trump on Native American issues wants to free those resources from what they call a suffocating federal bureaucracy that holds title to 56 million acres of tribal lands, two chairmen of the coalition told Reuters in exclusive interviews.

The group proposes to put those lands into private ownership – a politically explosive idea that could upend more than century of policy designed to preserve Indian tribes on U.S.-owned reservations, which are governed by tribal leaders as sovereign nations.

The tribes have rights to use the land, but they do not own it. They can drill it and reap the profits, but only under regulations that are far more burdensome than those applied to private property.

“We should take tribal land away from public treatment,” said Markwayne Mullin, a Republican U.S. Representative from Oklahoma and a Cherokee tribe member who is co-chairing Trump’s Native American Affairs Coalition. “As long as we can do it without unintended consequences, I think we will have broad support around Indian country.”

Trump’s transition team did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The plan dovetails with Trump’s larger aim of slashing regulation to boost energy production. It could deeply divide Native American leaders, who hold a range of opinions on the proper balance between development and conservation.

The proposed path to deregulated drilling – privatizing reservations – could prove even more divisive. Many Native Americans view such efforts as a violation of tribal self-determination and culture.

“Our spiritual leaders are opposed to the privatization of our lands, which means the commoditization of the nature, water, air we hold sacred,” said Tom Goldtooth, a member of both the Navajo and the Dakota tribes who runs the Indigenous Environmental Network. “Privatization has been the goal since colonization – to strip Native Nations of their sovereignty.”

Reservations governed by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs are intended in part to keep Native American lands off the private real estate market, preventing sales to non-Indians. An official at the Bureau of Indian Affairs did not respond to a request for comment.

The legal underpinnings for reservations date to treaties made between 1778 and 1871 to end wars between indigenous Indians and European settlers. Tribal governments decide how land and resources are allotted among tribe members.

Leaders of Trump’s coalition did not provide details of how they propose to allocate ownership of the land or mineral rights – or to ensure they remained under Indian control.

One idea is to limit sales to non-Indian buyers, said Ross Swimmer, a co-chair on Trump’s advisory coalition and an ex-chief of the Cherokee nation who worked on Indian affairs in the Reagan administration.

“It has to be done with an eye toward protecting sovereignty,” he said.

$1.5 TRILLION IN RESERVES

The Trump-appointed coalition’s proposal comes against a backdrop of broader environmental tensions on Indian reservations, including protests against a petroleum pipeline by the Standing Rock Sioux tribe and their supporters in North Dakota.

On Sunday, amid rising opposition, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers on Sunday said it had denied a permit for the Dakota Access Pipeline project, citing a need to explore alternate routes.

The Trump transition team has expressed support for the pipeline, however, and his administration could revisit the decision once it takes office in January.

Tribes and their members could potentially reap vast wealth from more easily tapping resources beneath reservations. The Council of Energy Resource Tribes, a tribal energy consortium, estimated in 2009 that Indian energy resources are worth about $1.5 trillion. In 2008, the Bureau of Indian Affairs testified before Congress that reservations contained about 20 percent of untapped oil and gas reserves in the U.S.

Deregulation could also benefit private oil drillers including Devon Energy Corp, Occidental Petroleum, BP and others that have sought to develop leases on reservations through deals with tribal governments. Those companies did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

Trump’s transition team commissioned the 27-member Native American Affairs Coalition to draw up a list of proposals to guide his Indian policy on issues ranging from energy to health care and education.

The backgrounds of the coalition’s leadership are one sign of its pro-drilling bent. At least three of four chair-level members have links to the oil industry. Mullin received about eight percent of his campaign funding over the years from energy companies, while co-chair Sharon Clahchischilliage – a Republican New Mexico State Representative and Navajo tribe member – received about 15 percent from energy firms, according to campaign finance disclosures reviewed by Reuters.

Swimmer is a partner at a Native American-focused investment fund that has invested heavily in oil and gas companies, including Energy Transfer Partners – the owner of the pipeline being protested in North Dakota. ETP did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The fourth co-chair, Eddie Tullis, a former chairman of the Poarch Band of Creek Indians in Alabama, is involved in casino gaming, a major industry on reservations.

Clahchischilliage and Tullis did not respond to requests for comment.

BUREAUCRATIC THICKET

Several tribes, including the Crow Nation in Montana and the Southern Ute in Colorado, have entered into mining and drilling deals that generate much-needed revenue for tribe members and finance health, education and infrastructure projects on their reservations.

But a raft of federal permits are required to lease, mortgage, mine, or drill – a bureaucratic thicket that critics say contributes to higher poverty on reservations.

As U.S. oil and gas drilling boomed over the past decade, tribes struggled to capitalize. A 2015 report from the Government Accountability Office found that poor management by the Bureau of Indian Affairs hindered energy development and resulted in lost revenue for tribes.

“The time it takes to go from lease to production is three times longer on trust lands than on private land,” said Mark Fox, chairman of the Three Affiliated Tribes in Forth Berthold, North Dakota, which produces about 160,000 barrels of oil per day.

“If privatizing has some kind of a meaning that rights are given to private entities over tribal land, then that is worrying,” Fox acknowledged. “But if it has to do with undoing federal burdens that can occur, there might be some justification.”

HISTORY OF ‘TERMINATION’

The contingent of Native Americans who fear tribal-land privatization cite precedents of lost sovereignty and culture.

The Dawes Act of 1887 offered Indians private lots in exchange for becoming U.S. citizens – resulting in more than 90 million acres passing out of Indian hands between the 1880s and 1930s, said Kevin Washburn, who served as Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs at the Department of the Interior from 2012 until he resigned in December 2015.

“Privatization of Indian lands during the 1880s is widely viewed as one of the greatest mistakes in federal Indian policy,” said Washburn, a citizen of Oklahoma’s Chickasaw Nation.

Congress later adopted the so-called “termination” policy in 1953, designed to assimilate Native Americans into U.S. society. Over the next decade, some 2.5 million acres of land were removed from tribal control, and 12,000 Native Americans lost their tribal affiliation.

Mullin and Swimmer said the coalition does not want to repeat past mistakes and will work to preserve tribal control of reservations. They said they also will aim to retain federal support to tribes, which amounts to nearly $20 billion a year, according to a Department of Interior report in 2013.

Mullin said the finalized proposal could result in Congressional legislation as early as next year.

Washburn said he doubted such a bill could pass, but Gabe Galanda, a Seattle-based lawyer specializing in Indian law, said it could be possible with Republican control of the White House and the U.S. House and Senate.

Legal challenges to such a law could also face less favorable treatment from a U.S. Supreme Court with a conservative majority, he said. Trump will soon have the chance to nominate a Supreme Court justice to replace Antonin Scalia, a conservative member who died earlier this year.

“With this alignment in the White House, Congress and the Supreme Court,” he said, “we should be concerned about erosion of self determination, if not a return to termination.”