State legislation is seeking to impose limits on discussions of racism in North Carolina, even as one city ramps up its effort to compensate Black residents.

Roughly 200 people gathered at the University of North Carolina at Asheville recently to discuss the city’s commitment to local reparations. It was the first summit of its kind and an important step in Asheville’s plan to compensate Black residents for decades of structural racism.

As the city ramps up its reparations effort, the state of North Carolina is moving in a reverse direction, with state legislation seeking to limit discussions about racism, especially in government and academia.

A new law passed in June forbids any employee of the North Carolina state government – which includes the University of North Carolina system – from discussing racism-related concepts, particularly in hiring practices.

In March, lawmakers in North Carolina’s state House of Representatives also passed a bill that prohibits public schools teachers from “promoting” ideas related to exposing systemic and historical racism. For example, teachers would be restrained from teaching concepts that say, “An individual, solely by virtue of his or her race or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past” that harmed another race. The bill hasn’t yet been passed by the senate.

According to University of North Carolina law professor Osamudia James, thesepieces of legislation are “unduly broad, they are very unclear, it is difficult to enforce them, and trying to figure out when someone has violated them is often a matter of debate.”

While neither bill names the reparations initiative,such legislation is already creating a hostile environment for proponents of reparations, local academics say.

“Diversity, equity, inclusion and justice is under attack,” said professor Tiece Ruffin, the director of UNC at Asheville’s Africana Studies department who helped host this year’s summit. “We’ve continued to center reparations for African Americans in the city. Although there may have been backlash and protests against certain things, we just say we’re going to continue doing this regardless.”

These bills are examples of two recent waves of state legislation: So-called anti-DEI lawstarget, among other things, efforts at diversity, equity and inclusion in hiring. Anti-critical race theory [CRT] laws, named for the collegiate-taught research that interrogates how racism is infused into US policies and institutions, seek to limit how teachers can discuss racism.Conservative lawmakers behind such bills argue that such instruction amounts to an “indoctrination.”

These kinds of laws have created dilemmas in other cities and states. In Oklahoma, a state commission created to investigate the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre removed GovernorKevin Stitt from its board after he signed an anti-critical race theory bill that prohibits how race-related issues can be taught and discussed.

Asked what impact these bills might have on the reparations effort, North Carolina state Senator Warren Daniel, sponsorof the anti-DEI law that passed in June, said, “I would hope any professors engaging the public on reparations would stick to informative discussions, instead of pushing the discriminatory notion that solely because of one’s race, an individual should bear responsibility for the actions committed in the past by other members of the same race.”

Reparations Leaders Undeterred

Asheville voted in July 2020 to create a reparations commission that would investigate how the city damaged individual Black families and entire Black neighborhoods through racist policies. This has involved more than two years of unearthing historical documents, property deeds, financial records, tax sheets and city ordinances.

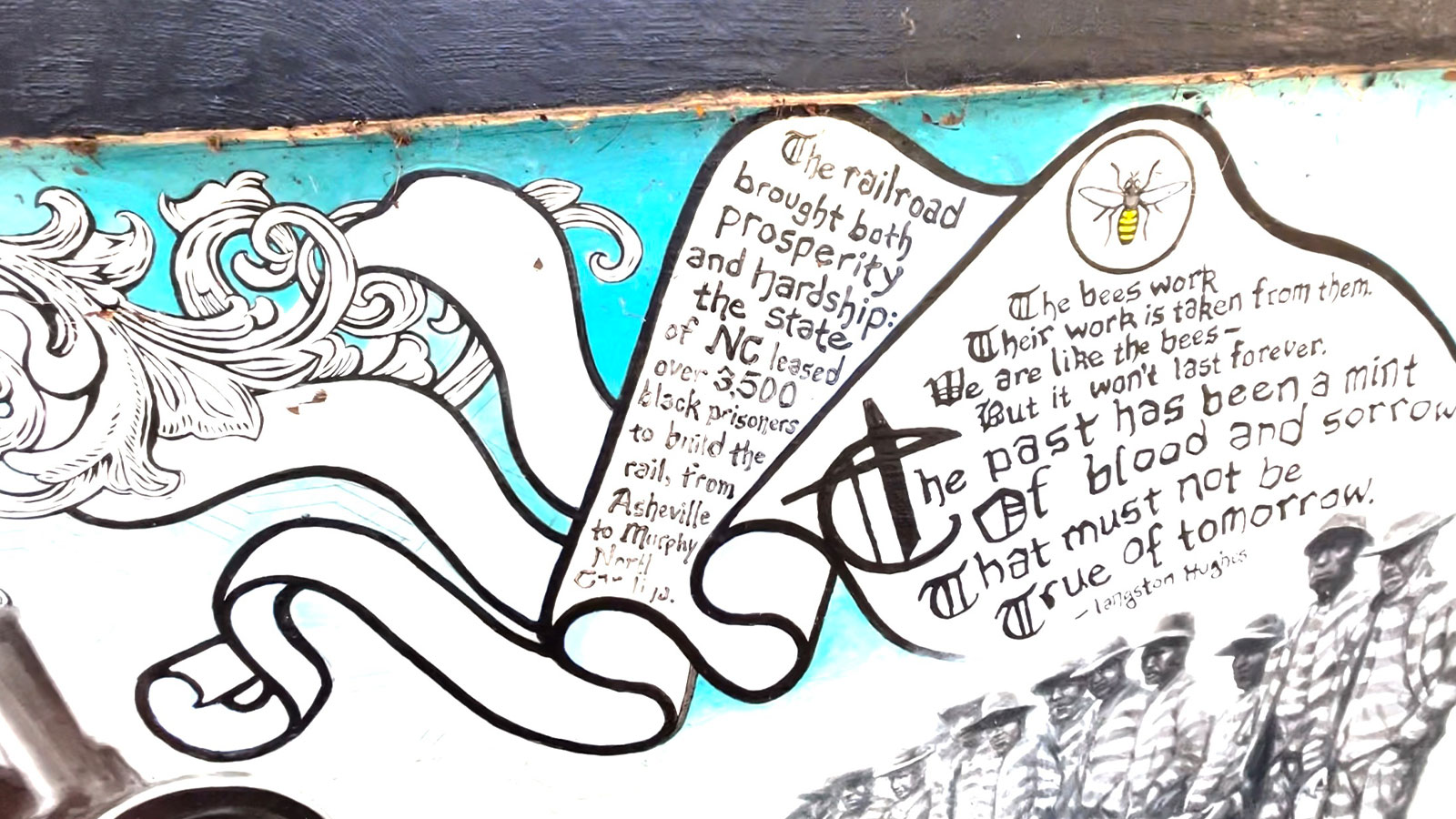

A mural in Triangle Park, in downtown Asheville, remembers the financial and cultural center of the city’s Black communities that was destroyed under a federal urban renewal plan. Photographer: Brentin Mock/Bloomberg CityLab

The new and proposed laws haven’t yet stopped any of this reparations work at the city level, said Dwight Mullen, chair of the city’s reparations commission. The commission members mostly have just ignored talk from conservatives about clamping down on how racism is taught and addressed in the state, said Mullen.

But both Mullen and Ruffin are already seeing the effect of the proposals on other areas of their work. Ruffin said state lawmakers have begun querying the university about how much funding is spent on DEI initiatives and about what kinds of questions the Africana Studies department asks when hiring professors and other staff.

Mullen has become embroiled in a federal civil rights complaint filed against Asheville PEAK Academy. The organization Western North Carolina Citizens for Equality named Mullen, a PEAK Academy founder and board member, in the complaint, which claims that the K-3 charter school employs “racial quotas” that exclude teachers and students of certain races.

“It is completely and justifiably legal to — in order to reverse and address racial harms perpetuated by the government — to use race as a means of addressing it,” said Mullen.

UNC School of Law professor James doesn’t think either of these bills would pass constitutional muster if challenged in court. But that’s “almost besides the point,” she says. “The point is to make people stop talking about these realities, which is a problem because if you cannot talk about race and recognize how it operates then you cannot do things to address its ongoing impacts.”

‘Local Governments Cannot Be the Complete Solution’

Resolutions that the city of Asheville and surrounding county passed call for the creation of a reparations commission to investigate racial harms, and for a report that outlines those harms and possible remedies. The commission will then make recommendations by spring 2024.

While Asheville was one of the few places in the South that did not have a slave plantation system, reparations advocates here say other government initiatives, such as segregation, Jim Crow ordinances, redlining and urban renewal devastated whole Black communities. In the 1950s and 1960s, hundreds of Black-owned homes, schools and health clinics were razed and a thriving Black business district was destroyed to build state highways.

Reparations advocates say those injustices are responsible for many of the racial disparities seen in Asheville today. According to the State of Black Asheville report, the cancer mortality rate from 2011 to 2015 was 218.9 per 100,000 for BLack residents compared to 155.1 for whites; the average per-capita income was $15,535 for Black residents compared to $28,480 for whites; and, as of 2017, there were just 858 Black-owned businesses compared to 26,122 white-owned.

Representatives of Asheville’s reparation commission discuss their recommendations at an Oct. 7 summit for community feedback. Photographer: Brentin Mock/Bloomberg CityLab

The reparations commission is focusing on five areas for investigation: criminal justice, economic development, housing, education and health. Some of the recommendations they are currently considering include funding for families impoverished by having members incarcerated; grants for Black-owned businesses; better salaries for Black teachers; payments to Black families that would be used exclusively for mental health support; and “reparations land” — properties and lots acquired exclusively for Black homeowners and entrepreneurs.

There are also non-compensation recommendations that focus more on policy, such as calls to eliminate racial disparities in the court system, to recruit and retain more Black teachers, and for the creation of a Black Economic Development Center to train Black business owners.

As a local government in a conservative state, the city may ultimately be constrained by which of these recommendations it can institute and how. In an email sent three days before the summit, the reparations commission cautioned that “local governments cannot be the complete solution to the problems faced by the Black community” due, in part, to legal limitations.

“In the end, the City and County stand with the Commission in focusing on the goal of investing in and empowering Black Asheville through the reparations process,” the letter states. “Yes, some proposals may be beyond our legal ability, and working through these challenges is simply part of the complex and important work being done by the Commission, the community, and our local governments. We remain focused on what is possible, rather than what is not.”

Source: Bloomberg

Brentin Mock is a writer and editor for CityLab in Pittsburgh, focused on issues of racial equity, economic inequities, and environment/climate justice.

Featured image: The intersection of Market and Eagle streets, where Black Asheville’s cultural and financial center once stood before it was razed during urban renewal policies. Photographer: Brentin Mock