“My God, Is Slavery Extinct?”: With stinging criticism of political elites, samba school invokes Brazil’s slave past as commentary on modern condition of the people

Note from BW of Brazil: As I took a pause in the action for some days of much needed relaxation, I mostly tuned out of this year’s Carnaval festivities. But thanks to YouTube, I was able to finally sit and watch and find out what all the fuss was about in regards to this year’s parades. After watching the show put on by the Paraíso do Tuiuti and Beija-Flor samba schools, I figured I needed to feature this story, even as the Carnaval season officially ended nearly two weeks ago. This is because, in their parade, the two schools brought to the fore numerous issues that are discussed on this blog. Brazil’s slavery past and the way that black Brazilians are to this day treated as if they are still living in the senzalas (slave quarters). Labor reform that, in effect, has chipped away at many rights of all Brazilian workers and left them in a state that many see as being just above slavery. An unpopular president, economic downturn and the people eeking out a living in favela slums of the hills, far away from the resources of city downtowns. Although there were a number of noteworthy performances, the scenarios enacted by these two schools alone were worthy of a Globo TV novela story line.

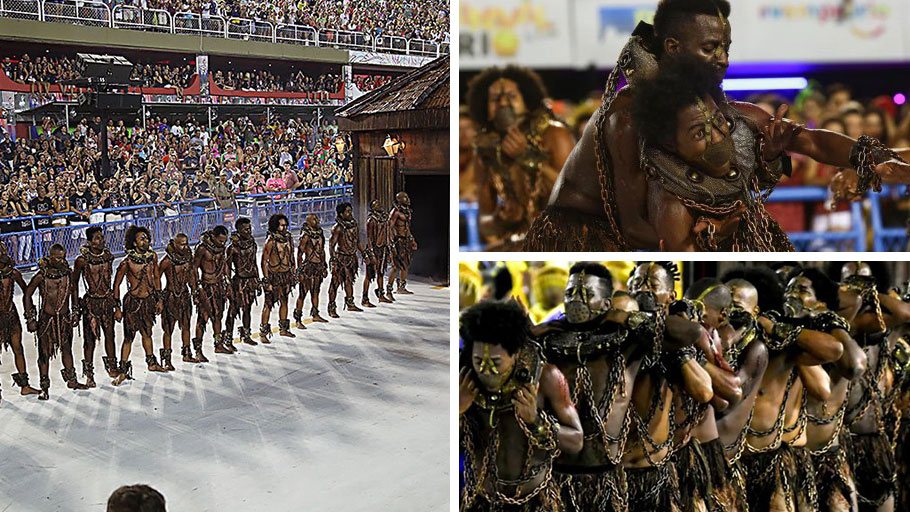

In protest parade, the Paraíso da Tuiuti samba school presented the Preto Velho (old black man), an enslaved folkloric figure that evokes African ancestors and loves to tell stories of the slavery era. Photo: Leo Correa

Carnival 2018 regained its critical spirit with the political class in Brazil

Criticism of the country’s situation moves from the streets to the sambodromes, with plots that directly attack political figures and government measures

By María Martín and Talita Bedinelli —

The Brazilian political crisis did not give way to this Carnival. Not only on the street, as it was more common in other years, but also in the sambodromes of Rio and São Paulo. The samba schools took to the avenue this year, blunt and very direct social criticisms.

The most striking case was that of Paraíso do Tuiuti, a samba school born on the hill of the same name, in São Cristovão, in Rio, which surprised the audience during the parade on Sunday night (11) and achieved enormous repercussion in social networks. With the samba plot Meu Deus, Meu Deus, Está Extinta a Escravidão? (My God, My God, Is Slavery Extinct?) the school criticized the working conditions in the country and, in fact, the current Government responsible for the labor reform approved last year.

The most striking case was that of Paraíso do Tuiuti, a samba school born on the hill of the same name, in São Cristovão, in Rio, which surprised the audience during the parade on Sunday night (11) and achieved enormous repercussion in social networks. With the samba plot Meu Deus, Meu Deus, Está Extinta a Escravidão? (My God, My God, Is Slavery Extinct?) the school criticized the working conditions in the country and, in fact, the current Government responsible for the labor reform approved last year.

Paraíso da Tuiuti Front Commission section presented the “cry of freedom:” I am no slave of any master; My Paradise is my bastion; My Tuiuti, the quilombo of the favela; It is sentinel of the liberation” (Photo: Pilar Olivares)

Thiago Monteiro, Carnival director of the school, explains to EL PAÍS that the plot was chosen by competition. “The goal was to deal with the exploitation of man by man. Not only of escravidão negreira (black slavery), but of this exploitation that extends for centuries, passing through the Egyptians, Celts, Romans and continues into the present day. To make a person work a 12-hour day, like the seamstresses, for a salary sometimes below the minimum salary and with mitigated rights, is to perpetuate this system,” he says.

Another highlight of the samba school was a very dirty work contract card, symbolizing the labor reforms passed by the government that trampled over the rights of workers nationwide

If the comissão de frente (front commission) the school brought O grito da Liberdade(The Scream of Liberty), showing slaves falling from the senzala (slave quarters) whipped, the last car came with a vampire dressed in the presidential belt, reminiscent of President Michel Temer. He was on top of the car called neo tumbeiro, that is, a slave ship of the present times. On the avenue were heard cries of “Fora, Temer” (Out, Temer), reported the newspaper O Globo.

Wing of parade made a criticism of the “puppet protestors” being guided by invisible force of the “hidden hand”

Between the last and the first car, the parade of 29 wings and 3,100 components still brought the manifestoches (puppet protestors) members dressed in green and yellow, the colors that marked the protests in favor of the impeachment of the ex- president Dilma Rousseff, being manipulated by an invisible hand and embedded in yellow ducks, symbol of the complaints against the former Government made by the Federation of Industries of the State of São Paulo (FIESP). They carried pots in their hands, another symbol of the protests.

President Michel Temer, who many Brazilians see as the culprit for of the country’s woes, was presented as a “Neo-liberal Vampire”.

“As we talked about the exploitation of man by man we wanted to include the mitigation of social rights. Through the ducklings you represent an earlier situation in which rights were well protected and from the moment a new political order takes the country you have new reforms that, from the point of view of the school, takes social rights from a portion of the population. The school wanted to question whether anyone who asked for this change is not a victim as well. Doesn’t this person who went to the street have these rights cut too?”, explained Monteiro.

Mangueira parade, which portrayed the mayor of Rio. (Photo” Leo Correa)

The explicit criticism of the Paraíso do Tuiuti left the commentators of TV Globo, which broadcasts live the carnival parades in silence. While the previous wings were explained in detail, the manifestoches received a quick and unique commentary of “manipulated, puppets,” then cut to a “Jú, 120 [centimeters] of a hip,” referring to the passer shown below in the image. In social networks, the school was praised for the “courage” of its criticism. “In the pre-Carnival, when the theme of the plot was released, we already had an interesting repercussion, but this great repercussion after the parade surprised us. We are very happy,” said the director of Carnaval. But there were also those who, on the Internet, considered the parade a “disservice” worthy of relegation.

More criticisms

More criticisms

The Mangueira samba school also brought a direct criticism to the current Mayor of Rio, Marcelo Crivella, on the first night of parades of the Rio Special Group, which was represented in one of the floats, such as a Judas doll, the type that is beaten on Sábado de Aleluia (Holy Saturday). The puppet of the evangelical politician was accompanied by the phrase: “Mayor, it is a sin not to play Carnival.” The school criticized the cut by City Hall of half of the money allocated to samba schools and had as a theme “Com dinheiro ou sem dinheiro, eu brinco” (With money or no money, I play).

Beija Flor samba school also took on social issues as a theme portraying the ‘monstrosities of society’, those that don’t know how to love (Photo: Mauro Pimentel)

Beija-Flor, parading on Monday night (12), will also bring a political Carnival to Sapucaí. With the theme Monstro (Monster) is the one who does not know how to love. The abandoned children of the motherland who gave birth must address the neglect of poor children and adolescents by making a connection with corruption.

A all too common scene in Rio de Janeiro – Violence in Rio was one of the themes presented by Beija Flor (Photo: Mauro Pimentel)

In São Paulo, there was also political criticism, with the return of X-9 Paulistana at the Special Group on Saturday – the car A Casa da Mãe Joana (The House of Mother Joana) brought politicians, some with the presidential banner, and judges represented as dirty from mud and with suitcases of money in their underwear.

The Paraíso da Tuiuti parade also criticized protestors that took to the streets against impeached former President Dilma. Called “manifestoches”,or “puppet protestors”, many believe they were manipulated by powerful political interests

Leonardo Bruno, a columnist for the Extra newspaper and a judge of the Estandarte de Ouro (Gold Standard), the unofficial prize of the Rio Carnival, believes that samba schools have never had much of a role in being so critical to society, something for him, more incorporated by street carnival. “Schools have always had a different characteristic, so much so that the samba storyline is considered an epic genre song, which narrates the great events, the great conquests, the great achievements,” he points out. “Now, on the other hand, what we observe is that in the most convulsive moments, when society is most in need of shouting against something, they appear to represent this role of social and political criticism,” he believes.

Another section of the Paraíso do Tuiuti parade represented replicas of favelas, Brazil’s poor communities. After abolition in 1888, many descendants of enslaved Africans were driven out of downtown regions into the outskirts and hills where they constructed these shantytowns

He points out that this was seen at two other times in the history of the schools. One, in the turn of the 60s to the 70s, the peak of the military dictatorship in Brazil. Three remarkable scenarios on this occasion spoke of freedom. The first, in 1967, when Salgueiro paraded A história da liberdade no Brasil (the history of freedom in Brazil). Two years later, in 1969, the Império Serrano spoke about the Heróis da Liberdade (Heroes of Freedom). And, at the 1972 Carnival, Vila Isabel took the theme Onde o Brasil aprendeu a liberdade (Where Brazil learned freedom). It was a time when censorship was at its peak and schools gave vent to this cry for freedom.

In the mid-1980s, he points out, Caprichosos de Pilares and São Clemente also spoke about the troubled moment of political openness in Brazil, when the people had not yet voted. They took to the avenue the cry of Direitas Já! (meaning Direct Elections Now!) and wore banners talking about the Constituent Assembly. “They were very critical scenarios for the time,” recalls Bruno. There was also, in 1989, the famous Beija-Flor parade, in which Joãosinho Trinta produced a Christ beggar, to criticize poverty, but the allegory was forbidden by the Courts at the request of the Church. By the end of the 90s and in the 2000s, when the country experienced more political and economic stability, the critical plots were left more to the side, stresses the journalist. “We have to think as a society the time in which we were as a country, because the schools reflect what is happening in the streets.” For these criticisms to have come to Sapucaí it’s because the moment is a very big crisis. The samba schools, in general, are the last point where this critical voice arrives, they are very resistant. It is a moment of upheaval at all levels of Government.”