The oldest living survivor of the Tulsa Massacre is a key witness for a national movement gaining momentum.

By Wesley Lowery, The Washington Post —

Her mother’s scream awoke the 7-year-old girl just moments after she’d drifted off to sleep. “Vi! Get up, child. If we don’t leave right now, we could end up dead.”

What Viola Fletcher witnessed that night in 1921 has haunted her for a century. Her entire childhood had been set ablaze. Families fled Tulsa’s bustling Greenwood district as torches flew through their windows. Explosives rained from low-flying planes that cut across a smoke-darkened sky above. Bodies piled along the roadside — some eyes still open, forever frozen on the terror — as soot stuck to the air like dark, bitter snowflakes. Fletcher watched a man with a shotgun blow a neighbor’s head from his shoulders, she writes in “Don’t Let Them Bury My Story,” a memoir published this year.

Fletcher, her family, and their entire neighborhood were the victims of a lie. Their lives were upended and livelihoods destroyed when hundreds of enraged White residents rioted after accusations that a 19-year-old Black man had assaulted a 17-year-old White girl, followed by inflammatory coverage of the alleged incident in the Tulsa Tribune. The man was arrested, and the accusations were false. The 16-hour terror left hundreds dead, thousands displaced and a stretch of 35 square blocks of Greenwood — a neighborhood so prosperous it was dubbed “Black Wall Street” — reduced to ash. Gone were offices of Black dentists, doctors, lawyers, real estate brokers and insurance salesmen. Black-owned theaters, newspapers, groceries, restaurants, hotels and barbershops were all burned to the ground.

Buildings burn during the Tulsa Race Massacre in the Greenwood District in June 1921. (Circa Images/GHI/Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images)

“The neighborhood I fell asleep in that night was rich — not just in terms of wealth, but in culture, community, heritage, and my family had a beautiful home,” Fletcher testified to Congress in 2021. “Within a few hours, all that was gone.”

In the years that followed, Fletcher’s family lived in a tent about an hour north of the city, settling into a new life as sharecroppers, lucky to earn a dollar for a day of handling livestock or picking cotton. Family members would often jolt awake, screaming about fire falling from the sky. When she was 16, Fletcher moved back to Tulsa, where “streets that bustled with life just a few years ago now carried the weight of trauma,” she writes. “The destruction,” she continues, “was just the visible version of the scars that were inside of us.”

Fletcher survived the Tulsa Race Massacre in 1921 at the age of seven. (Gioncarlo Valentine for The Washington Post; Wardrobe styling, hair and makeup by The Teknique Group)

Fletcher fled again, this time to California, where she took a shipyard job to support the war effort. She married but, when her husband turned abusive, set off again on her own. Before long, she was back in Oklahoma, a single mother of three with a fourth grade education, working as a maid to some of Tulsa’s richest White families.

As she washed their dishes and tucked their little ones into bed, she wondered whether they were among those responsible, yet never held accountable, for her own childhood’s destruction.

For as long as slavery has been outlawed in America, there have been Black Americans demanding compensation for the horrors of the institution and its vestiges. But in the years since the police killing of George Floyd, local governments, civil rights attorneys and activists have embraced the cause of financial redress with a new fervor and ambition: according to activists, there are more than 100 local efforts underway across the country.

Although many of these efforts, such as housing and economic stimulus programs, fall short of what purists would consider “reparations” — that is, direct payments to descendants of those who were victims of historic racial sins — they’ve nevertheless contributed to an era of redress.

“This is certainly one of the most significant moments in the history of the United States,” said Ron Daniels, who leads the National African American Reparations Commission, a collaborative of activists and academics. Daniels notes that Tulsa, “one of the most egregious wounds in the history of Black people in this country,” remains a key reparations battleground.

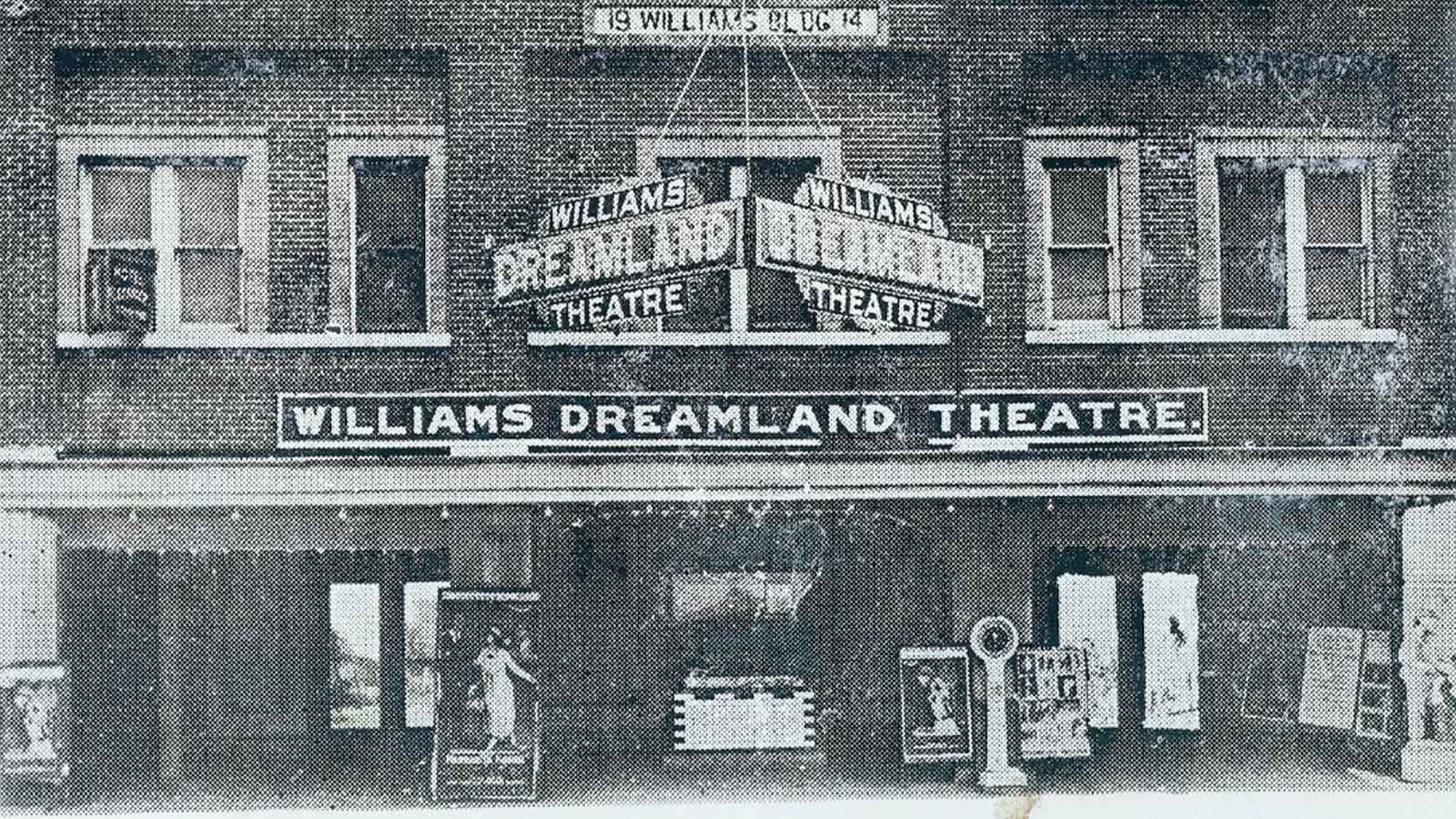

An exterior view of Williams Dreamland Theatre in Tulsa, which was destroyed during the massacre in 1921. (Greenwood Cultural Center/Getty Images)

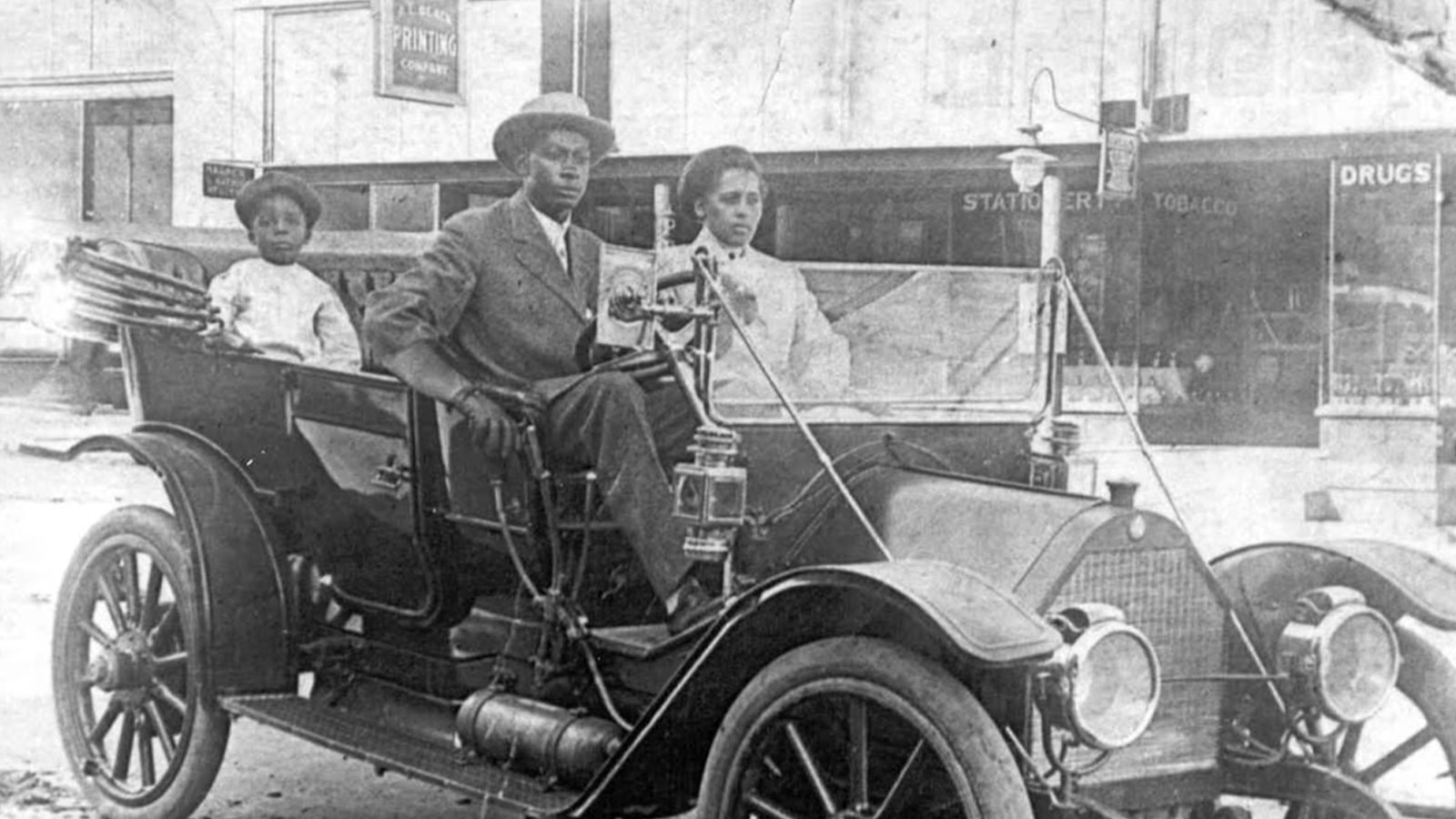

American businessman John Wesley Williams sits in his car with wife Loula Williams and their son, W.D. Williams in Tulsa in the 1910s. (Greenwood Cultural Center/Getty Images)

“If there is [any] case for a local reparations initiative for the harms faced by the Black community and the legacies of slavery, it’s Tulsa, Oklahoma,” said Robin Rue Simmons, who, as a member of the Evanston, Ill., city council, championed one of the first local redress efforts, which this year began making $25,000 payments to a few dozen Black residents.

And so, on the second Wednesday in May this year, Viola Fletcher spent the morning of her 109th birthday in the front row of a 7th floor courtroom at the Tulsa courthouse. She had dressed elegantly — her green and white blouse poking out from beneath the tan and white scarf wrapped around her shoulders for warmth — and sat silently, at times leaning forward in her wheelchair as she waited to learn whether the lawsuit that is probably her last living chance at justice would be allowed to proceed. To her right sat Lessie Benningfield Randle, 108, who was six years old when the mob burned her house to the ground and drove her family from Greenwood, and between them sat Fletcher’s younger brother Hughes “Uncle Red” Van Ellis, 102, who at times dabbed tears from his eyes with an aging white handkerchief.

“There were over 10,000 people that suffered, these are the three that’s left. No one had a day in court. They just want a day in court,” attorney Damario Solomon-Simmons pleaded to the judge as he gestured back toward the galley where the survivors sat.

Damario Solomon-Simmons outside of the Oklahoma Supreme Court in Oklahoma City on Aug. 7. (Nick Oxford for The Washington Post)

“She had to escape this inferno,” he added later, pointing to Fletcher and then back up at the black-and-white photos of the charred wreckage that were being projected onto a screen hung from the courtroom’s side wall. “One hundred and two years later she has to be here in court.”

Fletcher’s case is the second time in recent decades in which a court has considered compensation for those who survived the inferno. The first came in 2003, when a legal team led by Johnnie Cochran, Charles Ogletree, and John Hope Franklin filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of 123 survivors and more than 200 descendants. There were government defendants clearly culpable for the crime, thanks to a 1997 bipartisan commission that concluded that local law enforcement had provided firearms to the White rioters. But in Oklahoma, civil rights claims carry a two-year statute of limitations, meaning that the suit would have had to have been filed in 1923, and the case for a waiver was denied.

In 2007, Solomon-Simmons (who clerked for Ogletree as a law student) and others pursued congressional legislation that would have removed the statute of limitations in the case, but the bill never made it out of committee. “Our momentum really hit a halt,” he recalled recently. “A lot of the survivors were dying.” By 2016, fewer than 20 remained, and with each passing year the list whittled further. Each year, around the anniversary, he would publish an op-ed calling for redress, but justice seemed an increasingly distant fantasy.

Then, in May 2020, Solomon-Simmons stumbled upon the story of Viola Fletcher.

For decades, many of the massacre’s victims feared that the perpetrators would harm them again if they ever spoke about it publicly. Fletcher told me she still slept with a light on, curled up in a living room chair pointed toward the door of her apartment — ready, if necessary, to make another escape. She never talked about what she had survived with anyone.

“They were told by their parents that if they discussed it they would be killed,” explains Ike Howard, Fletcher’s grandson, who after many years finally got her to acknowledge that she had witnessed the massacre — but only on the explicit condition that he not repeat the tale. “You had a situation where the local government had endorsed this behavior and these criminals got away … This is one generation removed from slavery, the threat of violence if they talked about what happened was something they took seriously.”

Fletcher with her grandson, Ike Howard. (Gioncarlo Valentine for The Washington Post)

But in the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, Fletcher agreed to let her loved ones tell the local news about the drive-by birthday parade they threw to celebrate her 106th birthday, inadvertently outing her as the oldest living survivor of the massacre just one year before its centennial. “I told them I didn’t want a birthday party,” she quipped to a local television reporter. “But what did I get? Oh my goodness.”

From there, it didn’t take long for Solomon-Simmons to track her down, and she agreed to join his pursuit of reparations — becoming a plaintiff in a civil suit filed in 2020 demanding financial redress from the city, county and other municipal entities that participated in the destruction. “She was still afraid,” Howard recalled, adding that he and other family members were able to convince her they would handle her security and that, as more time passed and she spoke out more frequently, she became more comfortable. “She know I don’t play about my grandmother.”

As the case began making its way through court, the 100th anniversary of the massacre brought a wave of attention, and money, to Tulsa. More than $30 million was spent constructing a historical center, and events commemorated the date. Fletcher testified before Congress, was honored in Ghana, and began working on her memoir. Moved by media coverage of their ongoing battle for justice, New York philanthropist Ed Mitzen gave $1 million to Fletcher and the other living survivors. Fletcher left her one bedroom apartment and moved into one of the nicest nursing homes in the state.

Members of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, with State Sen. Kevin Matthews in front, cheer in front of the Greenwood Rising Black Wall St. History Center before a dedication in June 2021 in Tulsa. (Mike Simons/Tulsa World/AP)Members of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, with State Sen. Kevin Matthews in front, cheer in front of the Greenwood Rising Black Wall St. History Center before a dedication in June 2021 in Tulsa. (Mike Simons/Tulsa World/AP)

Still, Solomon-Simmons is quick to note, none of this amounted to redress. In fact, he says that one foundation told him directly that there was “no appetite” among local philanthropy for providing the survivors with money that could be passed on to their children and grandchildren.

“The reality is that, in the United States of America, the only time Black people in particular have ever received any justice has been through litigation,” said Tulsa Councilwoman Vanessa Hall-Harper, who helped spearhead an apology issued by the city of Tulsa two years ago. As attorneys argued publicly for compensation, Black members of the Tulsa city council moved to capitalize on the centennial — introducing a bill issuing a formal apology and agreeing to hold community sessions on what, if anything else, the city owes to survivors of the massacre and their descendants.

The sessions, dubbed “After Apology,” were led in part by Greg Robinson, a local activist who still remembers his father pointing out blight and redevelopment in Greenwood through the car window as they drove past, saying “they are building buildings on top of your ancestors’ homes.” Each session included an overview of the historical record (and the long fight to establish it) and an analysis of the racial inequities that persist in Tulsa today. More than 500 people participated in total, about 35 percent of whom were White, although it remains unclear what, if any, action will result from the process.

“It’s almost like House of Cards on a political level,” said Keith Young, a political strategist and former elected official in Asheville, N.C., where he helped spawn reparations efforts. Young consulted with Black lawmakers in Tulsa as they debated how to navigate the issue. “They are never going to call it reparations, and it ain’t reparations. It’s not. It’s a Trojan horse.”

The concept of reparations is broadly unpopular: 70 percent of Americans in a May Washington Post-Ipsos poll said that the federal government should not pay money to Black Americans whose ancestors were enslaved. That’s especially true when the would-be recipients are Black, notes Tatishe Nteta, a political scientist and pollster at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. A key factor in opposition, his research shows, is that some Americans (28 percent) do not believe that Black Americans deserve to be compensated. “It’s all about deservingness,” Nteta said. “It’s really informed by negative racial views and stereotypes of African Americans, and what they would do with the money.” A 75 percent majority of Black Americans support the federal government paying reparations.

The short-term workaround, Nteta and others note, is to pursue reparations and redress programs in liberal cities and safely Democratic states to set precedent and build momentum that could spread nationally, much like legalized marijuana and same-sex marriage. Even if some local redress programs are not technically reparations, “I like to tell people that they’re cousins. At the heart of it we’re still talking about addressing the results of racism,” says attorney Areva Martin, who represents hundreds of survivors and descendants of “Section 14,” a one-square-mile tract in downtown Palm Springs razed in the mid-1960s to make way for development. That case is part of a wave of efforts that have made California an epicenter of the current movement for reparations and redress.

That makes Tulsa an even more crucial battleground: a majority-White, Republican-run southern city where there remain living victims of a historic injustice.

“We’re on borrowed time. Every year that we don’t get economic justice for Black people, generations behind us are being set further and further behind,” said Robinson. “If you can get it done in Tulsa, it just sets up so beautifully for a national model.”

Viola Fletcher’s lawsuit was designed as a bit of a legal bank shot. Because the civil rights claim had been tossed in the early 2000s, Solomon-Simmons modeled his effort on a 2019 suit filed by the Oklahoma attorney general’s office against Johnson & Johnson under the public nuisance act, which successfully argued that the drugmaker had fueled the opioid epidemic with deceptive marketing of painkillers.

The city, state and law enforcement agencies had aided the violence in Tulsa, Solomon-Simmons argued, and that violence and destruction still directly contributed to the inequitable reality experienced by residents of Greenwood today. Government attorneys argued the case was an attempt at dodging the statute of limitations issues and should be dismissed. Ultimately, in May 2022, Tulsa County District Judge Caroline Wall allowed it to move forward.

Part of Greenwood district burned during the Tulsa race massacre, Tulsa, Oklahoma, in June 1921.

A Black man with a camera looks at the skeletons of iron beds which rise above the ashes of a burned-out block after the massacre in June 1921.

“I’ve seen so many survivors die in my 20-plus years working on this issue,” Solomon-Simmons said, choking back tears, as he addressed the media following the ruling. “I just don’t want to see the last three die without justice.”

The legal proceedings stretched on until this May’s hearing, after which Uncle Red declared “we’re going to win” from his wheelchair as the legal team gathered in the hallway. Fletcher was less confident, sitting in silence as she stretched her neck to point her one remaining good ear toward the conversation among her attorneys.

Judge Wall announced that she wanted more time to make her ruling, but the decision stretched from days to weeks — which Fletcher and her family took as an ominous sign. “There is a sense,” Fletcher’s grandson remarked as the family waited, “that they are waiting for someone to die. That they’re hoping someone will die.”

It was another two months before word came out, late on a Friday evening in July: Wall came down in favor of the defendants, tossing the public nuisance claim. Solomon-Simmons said he heard about the ruling when a local reporter reached out to ask for comment.

Viola Fletcher (Gioncarlo Valentine for The Washington Post)

Fletcher and her family were heartbroken. Their supporters were enraged. Solomon-Simmons and his team quickly began preparing an appeal. During a phone interview a few weeks later, Fletcher was direct and emphatic when asked if she still believed she had a chance of seeing justice in her lifetime: “yes, yes, yes.”

A few weeks after that, in early August, her attorney called with a new hope: The state Supreme Court had decided to take up the case. The century-long fight was alive again.

Source: The Washington Post