Schooled

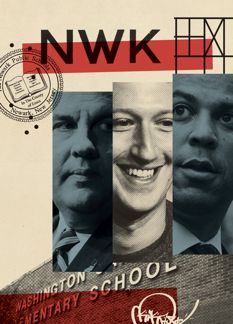

Cory Booker, Chris Christie, and Mark Zuckerberg had a plan to reform Newark’s schools. They got an education.

by Dale Russakoff

I. THE PACT

Late one night in December, 2009, a black Chevy Tahoe in a caravan of cops and residents moved slowly through some of the most dangerous neighborhoods of Newark. In the back sat the Democratic mayor, Cory Booker, and the Republican governor-elect of New Jersey, Chris Christie. They had become friendly almost a decade earlier, during Christie’s years as United States Attorney in Newark, and Booker had invited him to join one of his periodic patrols of the city’s busiest drug corridors.

The ostensible purpose of the tour was to show Christie one of Booker’s methods of combatting crime. But Booker had another agenda that night. Christie, during his campaign, had made an issue of urban schools. “We’re paying caviar prices for failure,” he’d said, referring to the billion-dollar annual budget of the Newark public schools, three-quarters of which came from the state. “We have to grab this system by the roots and yank it out and start over. It’s outrageous.”

Booker had been a champion of vouchers and charter schools for Newark since he was elected to the city council, in 1998, and now he wanted to overhaul the school district. He would need Christie’s help. The Newark schools had been run by the state since 1995, when a judge ended local control, citing corruption and neglect. A state investigation had concluded, “Evidence shows that the longer children remain in the Newark public schools, the less likely they are to succeed academically.” Fifteen years later, the state had its own record of mismanagement, and student achievement had barely budged.

Christie often talked of having been born in Newark, and Booker asked his driver to take a detour to Christie’s old neighborhood. The Tahoe pulled to a stop along a desolate stretch of South Orange Avenue, where Christie said he used to take walks with his mother and baby brother. His family had moved to the suburbs in 1967, when he was four, weeks before the cataclysmic Newark riots. An abandoned three-story building, with gang graffiti sprayed across boarded-up windows, stood before them on a weedy, garbage-strewn lot. Dilapidated West Side High School loomed across the street. About ninety per cent of its students qualified for free or reduced-price lunches, and barely half of the freshmen made it to graduation. Three West Side seniors had been shot and killed by gangs the previous school year, and the year before that, on a warm summer night, local members of a Central American gang known as MS-13, wielding guns, a machete, and a steak knife, had murdered three college-bound Newark youths, two of them from West Side. Another West Side graduate had been badly maimed.

In the back seat of the S.U.V., Booker proposed that he and Christie work together to transform education in Newark. They later recalled sharing a laugh at the prospect of confounding the political establishment with an alliance between a white suburban Republican and a black urban Democrat. Booker warned that they would face a brutal battle with unions and machine politicians. With seven thousand people on the payroll, the school district was the biggest public employer in a city of roughly two hundred and seventy thousand. As if spoiling for the fight, Christie replied, “Heck, I got maybe six votes in Newark. Why not do the right thing?”

So began one of the nation’s most audacious exercises in education reform. The goal was not just to fix the Newark schools but to create a national model for how to turn around an entire school district.

The abysmal performance of schools in the poorest communities has been an escalating national concern for thirty years, with universities, governments, and businesses devoting enormous resources to the problem. In the past decade, a reform movement financed by some of the nation’s wealthiest philanthropists has put forward entrepreneurial approaches: charter schools, business-style accountability for teachers and principals, and merit bonuses for top performers. President Obama and Secretary of Education Arne Duncan created Race to the Top, a $4.3-billion initiative to induce states to approve more charter schools and to rate teachers based on student performance.

Christie’s response to Booker—“Why not do the right thing?”—reflected the moral tone of the movement. Reformers compared their cause to the civil-rights movement, aware that many of their key opponents were descendants of the old civil-rights establishment: unions and urban politicians determined to protect thousands of public jobs in cities where secure employment was rare. Decades of research have shown that experiences at home and in neighborhoods have far more influence on children’s academic achievement than classroom instruction. But reformers argued that well-run schools with the flexibility to recruit the best teachers could overcome many of the effects of poverty, broken homes, and exposure to violence. That usually meant charter schools, which operated free of the district schools’ large bureaucracies and union rules. “We know what works,” Booker and other reformers often said. They blamed vested interests for using poverty as an excuse for failure, and dismissed competing approaches as incrementalism. Education needed “transformational change.” Mark Zuckerberg, the twenty-six-year-old head of Facebook, agreed, and he pledged a hundred million dollars to Booker and Christie’s cause.

Almost four years later, Newark has fifty new principals, four new public high schools, a new teachers’ contract that ties pay to performance, and an agreement by most charter schools to serve their share of the neediest students. But residents only recently learned that the overhaul would require thousands of students to move to other schools, and a thousand teachers and more than eight hundred support staff to be laid off within three years. In mid-April, seventy-seven members of the clergy signed a letter to Christie requesting a moratorium on the plan, citing “venomous” public anger and “the moral imperative” that people have power over their own destiny. Booker, now a U.S. senator, said in a recent interview that he understood families’ fear and anger: “My mom—she would’ve been fit to be tied with some of what happened.” But he characterized the rancor as “a sort of nadir,” and predicted that in two or three years Newark could be a national model of urban education. “That’s pretty monumental in terms of the accomplishment that will be.”

Booker was part of the first generation of black leaders born after the civil-rights movement. His parents had risen into management at I.B.M., and he grew up in the affluent, almost all-white suburb of Harrington Park, about twenty miles from Newark. Six feet three, gregarious, and charismatic, Booker was an honors student and a football star. He graduated from Stanford and went on to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar and then to Yale Law School. Ed Nicoll, a forty-year-old self-made millionaire who was studying law at Yale, became one of his close friends. He recalled Booker telling inspirational stories about his family during abstract class discussions, invariably ending with a point about social justice. “He got away with it and he enchanted everyone from left to right,” Nicoll said. “In a class where everybody secretly believed they’d be the next senator or the next President of the United States, it was absolutely clear that Cory had leadership written all over him.”

Instead of pursuing lucrative job prospects, Booker worked as a lawyer for Newark tenants; he was paid by a Skadden fellowship in 1997. He lived in low-income housing in an area of the Central Ward that was riddled with drugs and crime, and he got to know community activists and members of the national media. Later, CBS News and Time featured him staging hunger strikes to demand more cops in drug corridors. He ran for city council with enthusiastic support from public-housing tenants. Nicoll took time off before going back to finance to help Booker raise money. His advice was simple: tell wealthy donors your own story. Over lunch at Andros Diner, Booker told me that Nicoll taught him an invaluable lesson: “Investors bet on people, not on business plans, because they know successful people will find a way to be successful.”

Booker raised more than a hundred and forty thousand dollars, an unheard-of sum for a Newark council race. A Democratic operative said of enthusiasts on Wall Street, “They let Cory into their boardrooms and offices, introduced him to people they worked with in hedge funds. As young finance people, they looked at a guy like Cory at this stage as if they were buying Google at seventy-five dollars a share. They were talking about him being the first black President before he even got elected to the city council, and they all wanted to be a part of that ride.” In the spring of 1998, Booker, at the age of twenty-nine, edged out the four-term councilman George Branch.

The school-reform movement, then dominated by conservative white Republicans, saw Booker as a valuable asset. In 2000, he was invited to speak at the Manhattan Institute, in New York. He was an electrifying speaker, depicting impoverished Newark residents as captives of nepotistic politicians, their children trapped in a “repugnant” school system. “I define public education not as a publicly guaranteed space and a publicly run, publicly funded building where our children are sent based on their Zip Code,” he said. “Public education is the use of public dollars to educate our children at the schools that are best equipped to do so—public schools, magnet schools, charter schools, Baptist schools, Jewish schools.”

Booker told me that the speech launched his national reputation: “I became a pariah in Democratic circles for taking on the Party orthodoxy on education.” But he gained “all these Republican donors and donors from outside Newark, many of them motivated because we have an African-American urban Democrat telling the truth about education.” He became a sought-after speaker at fund-raisers for charter and voucher organizations, including a group of hedge-fund managers who ultimately formed Democrats for Education Reform. They supported Democrats who backed reforms opposed by teachers’ unions, including the 2004 U.S. Senate candidate from Illinois, Barack Obama.

There was no question that the Newark school district needed reform. For generations, it had been a source of patronage jobs and sweetheart deals for the connected and the lucky. As Ross Danis, of the nonprofit Newark Trust for Education, put it, in 2010, “The Newark schools are like a candy store that’s a front for a gambling operation. When a threat materializes, everyone takes his position and sells candy. When it recedes, they go back to gambling.”

The ratio of administrators to students—one to six—was almost twice the state average. Clerks made up thirty per cent of the central bureaucracy—about four times the ratio in comparable cities. Even some clerks had clerks, yet payroll checks and student data were habitually late and inaccurate. Most school buildings were more than eighty years old, and some were falling to pieces. Two nights before First Lady Michelle Obama came to Maple Avenue School, in November, 2010, to publicize her Let’s Move! campaign against obesity—appearing alongside Booker, a national co-chair—a massive brick lintel fell onto the front walkway. Because the state fixed only a fraction of what was needed, the school district spent ten to fifteen million dollars a year on structural repairs—money that was supposed to be used to educate children.

What happened inside many buildings was even worse. In a third of the district’s seventy-five schools, fewer than thirty per cent of children from the third through the eighth grade were reading at grade level. The high-school graduation rate was fifty-four per cent, and more than ninety per cent of graduates who attended the local community college required remedial classes. Booker was elected mayor in 2006, and, with no power over district schools, he set out to recruit charter schools. He raised twenty million dollars for a Newark Charter School Fund from several Newark philanthropies; from the Gates, Walton, Robertson, and Fisher foundations; and from Laurene Powell Jobs. With his encouragement, Newark spawned some of the top charter schools in the country, including fifteen run by Uncommon Schools and KIPP. Parents increasingly enrolled children in charters—particularly in wards with the highest concentrations of low-income and black residents, which had the worst public schools. Many district schools were left with a preponderance of the students who most needed help.

It wasn’t always this way. The Newark public schools had a reputation for excellence well into the nineteen-fifties, when Philip Roth graduated from the predominantly Jewish Weequahic High School and Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones), the late African-American poet, playwright, and revolutionary, attended the predominantly Italian-American Barringer High School. But Newark’s industrial base had been declining since the Depression, and it collapsed in the sixties, just as the migration of mostly poor African-Americans from the rural South reached its peak. Urban renewal, which was supposed to revive inner cities, displaced a higher percentage of poor residents in Newark than in any other city. As slums and dilapidated buildings were bulldozed to make way for office towers and civic plazas, displaced families were concentrated in five large housing projects in the city’s Central Ward. The program became known, there and elsewhere, as “Negro removal.”

Middle-class whites fled the city. Interstate 280, which linked downtown to the western suburbs and had an exit for Livingston, where the Christies moved, decimated stable Newark neighborhoods. Within a decade, the city’s population shifted from two-thirds white to two-thirds black. According to Robert Curvin, the author of the forthcoming book “Inside Newark,” it was the fastest and most tumultuous turnover of any American city except Detroit and Gary, Indiana. Remaining white students transferred out of largely African-American schools, where substitutes taught up to a quarter of the classes. “In schools with high Negro enrollments,” the N.A.A.C.P. reported, “textbooks were either not available or so outmoded and in such poor condition as to be of no value.” Some classrooms contained nothing but comic books.

Many in Newark still refer to the 1967 riots as “the rebellion.” A flagrantly corrupt and racist Italian-American political machine controlled City Hall and the school district. The mayor, Hugh Addonizio, previously a U.S. representative, said, when he returned, “There’s no money in Washington, but you can make a million bucks as the mayor of Newark.” In 1970, he was convicted, with four others, of having extorted $1.4 million from city contractors. The next two mayors, Kenneth Gibson and Sharpe James, both African-American, also became convicted felons. Booker is the first Newark mayor in fifty years not to be indicted.

In 1967, Governor Richard Hughes appointed a committee to investigate the causes of the riots. The report concluded of urban renewal, “In the scramble for money, the poor, who were to be the chief beneficiaries of the programs, tended to be overlooked.” And, because of “ghetto schools,” most poor and black children “have no hope in the present situation. A few may succeed in spite of the barriers. The majority will not. Society cannot afford to have such human potential go to waste.”

The legislature rejected a bid by Hughes to take over the schools, and the cycle of neglect and corruption continued. In 1994, Department of Education investigators found that the district was renting an elementary school infested with rats and containing asbestos and high levels of lead paint. The school board was negotiating to buy the building, worth about a hundred and twenty thousand dollars, for $2.7 million. It turned out to be owned, through a sham company, by two school principals prominent in Italian-American politics. (They were indicted on multiple charges and acquitted.) In a series of rulings in the nineties, the state Supreme Court found that funding disparities among school districts violated the constitutional right to an education for children in the poorest communities. The legislature was instructed to spend billions of dollars to equalize funding. In 1995, the state seized control of the Newark district. Christie, though, has allocated less than is required for low-income districts, pleading financial constraints.

Decades after the Hughes report, Newark’s education system was still dominated by “ghetto schools.” Forty per cent of babies born in Newark in 2010 received inadequate prenatal care or none at all—disadvantaged before drawing their first breath. Forty-four per cent of children lived below the poverty line—about twice the national rate—and many were traumatized by violence. Ninety-five per cent of students in the school district were black or Latino.

The history of abandonment and failed promises sowed a deep sense of isolation and a wariness of outsiders. “Newark suffers from extreme xenophobia,” Ronald C. Rice, a city councilman, said. “There’s a feeling that whites abandoned the city after the rebellion but there will come a time they will come back and take it away from us.”

Early in the summer of 2010, Booker presented Christie with a proposal, stamped “Confidential Draft,” titled “Newark Public Schools—A Reform Plan.” It called for imposing reform from the top down; a more open political process could be taken captive by unions and machine politicians. “Real change has casualties and those who prospered under the pre-existing order will fight loudly and viciously,” the proposal said. Seeking consensus would undercut real reform. One of the goals was to “make Newark the charter school capital of the nation.” The plan called for an “infusion of philanthropic support” to recruit teachers and principals through national school-reform organizations; build sophisticated data and accountability systems; expand charters; and weaken tenure and seniority protections. Philanthropy, unlike government funding, required no public review of priorities or spending. Christie approved the plan, and Booker began pitching it to major donors.

In the previous decade, the foundations of Microsoft’s Bill Gates, the California real-estate and insurance magnate Eli Broad, the Walton family (of the Walmart fortune), and other billionaires from Wall Street to Silicon Valley had come to dominate charitable funding to education. Dubbed “venture philanthropists,” they called themselves investors rather than donors and sought returns in the form of sweeping changes to public schooling. In addition to financing the expansion of charter schools, they helped finance Teach for America and the development of the Common Core State Standards to increase the rigor of instruction.

At the start of Booker’s career, Ed Nicoll had introduced him to a Silicon Valley venture capitalist named Marc Bodnick, who became an admirer. Bodnick was an early investor in Facebook, and he married the sister of Sheryl Sandberg, who later became the company’s chief operating officer. In June, 2010, Bodnick tipped off Booker that Mark Zuckerberg was planning “something big” in education. Bodnick also told him that in July Sandberg and Zuckerberg would be attending a media conference in Sun Valley, Idaho, where Booker was scheduled to speak. Booker said Bodnick told him to be sure to seek out Sandberg, who would connect him to Zuckerberg.

Booker by then was a national celebrity. Since his election as mayor of Newark, he had won widespread attention for presiding over a major decline in homicides—from a hundred and five in 2006 to sixty-seven in 2008. That year, for the first time in almost half a century, there were forty-three days without a single murder. Developers were negotiating deals to build the first downtown hotels in forty years, the first supermarkets in more than twenty. Philanthropists were paying to redevelop parks. A popular cable-TV series—“Brick City,” a reality show about Booker’s battle against crime—was about to begin its second season. Booker spoke at college commencements and charity dinners and appeared on late-night talk shows. His Twitter following, which was more than a million, outnumbered Newark residents almost four to one. Oprah Winfrey, a friend since the early two-thousands, pronounced him the “rock-star mayor of Newark.”

Booker met Zuckerberg over dinner on the deck of the Sun Valley retreat of Herbert Allen, the New York investment banker who hosted the conference. Zuckerberg invited Booker to go for a walk. He said that he was looking for a city that was ready to revolutionize urban education. Booker remembered responding, “The question facing cities is not ‘Can we deal with our most difficult problems—recidivism, health care, education?’ The real question is ‘Do we have the will?’ ” He asked, Why not take the best models in the country for success in education and bring them to Newark? You could flip a whole city! Zuckerberg told reporters, “This is the guy I want to invest in. This is a person who can create change.”

Zuckerberg was disarmingly open regarding how little he knew about urban education or philanthropy. Six years earlier, as a sophomore at Harvard, he had dropped out to work on Facebook. He had recently joined Gates and Warren Buffett in pledging to give half his wealth to charity. He’d never visited Newark, but he said he planned to learn from the experience and become a better philanthropist in the process.

Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, whom he met at Harvard, embarked on education philanthropy as a couple, but they brought different perspectives. Chan grew up in what she has described as a disadvantaged family in Quincy, Massachusetts. Her Chinese-Vietnamese immigrant parents worked eighteen hours a day, and her grandparents took care of her. Chan was the first in her immediate family to go to college, and credited public-school teachers with encouraging her to reach for Harvard. While there, she volunteered five days a week at two housing projects in Dorchester, helping children with academic and social challenges. She had since become a pediatrician, caring for underserved children. She came to see their challenges at school as inseparable from their experience with poverty, difficulties at home, and related health issues, both physical and emotional.

Zuckerberg told me that he had been more influenced by a year, after college, that Chan spent teaching science at an affluent private school in San Jose. People that he and Chan met socially often “acted like she was going to do charity,” he said. “My own view was: you’re going to have more of an impact than a lot of these other people who are going into jobs that are paying a lot more. And that’s kind of a basic economic inefficiency. Society should value these roles more.” Zuckerberg had come to see teaching in urban schools as one of the most important jobs in the country, and he wanted to make it as attractive to talented college graduates as working at Facebook. He couldn’t succeed in business without having his pick of the best people—why should public schools not have the same?

Zuckerberg attracted young employees to Facebook with signing bonuses far exceeding the annual salary of experienced Newark teachers. The company’s workspace had Ping-Pong tables, coolers stocked with Naked juice, and red-lettered motivational signs: “STAY FOCUSED AND KEEP SHIPPING”; “MOVE FAST AND BREAK THINGS”; “WHAT WOULD YOU DO IF YOU WEREN’T AFRAID?” In the Newark schools, nothing moved fast, and plenty of people were afraid. Like almost every public-school district, Newark paid teachers based on seniority and on how many graduate degrees they had earned, although neither qualification guaranteed effectiveness. Teachers who changed students’ lives were paid on the same scale as the deadwood. “Who would want to work in a system like that?” Zuckerberg wanted to know.

A month after their walk in Sun Valley, Booker gave Zuckerberg a six-point reform agenda. Its top priority was a new labor contract that would significantly reward Newark teachers who improved student performance. “Over the long term, that’s the only way they’re going to get the very best people, a lot of the very best people,” Zuckerberg told me. He proposed that the best teachers receive bonuses of up to fifty per cent of their salary, a common incentive in Silicon Valley but impossible in Newark. The district couldn’t have sustained it once Zuckerberg’s largesse ran out.

Booker asked Zuckerberg for a hundred million dollars over five years. “We knew it had to be big—we both thought it had to be bold, eye-catching,” he said. Zuckerberg stipulated that Booker would have to raise a second hundred million dollars, and that he would release his money only as matching dollars came in. Booker also promised that the current superintendent would be replaced by a “transformational leader.” Christie recounted his call from Booker afterward: “He said, ‘Governor, I believe I can close this deal. I really do. I need you, though.’ ” Christie did not grant Booker’s request for mayoral control of the schools but made him an unofficial partner in all decisions, beginning with the selection of a superintendent.

Zuckerberg and Chan flew to Newark Liberty Airport and met Booker and Christie in the Continental Airlines Presidents Club. Booker got Zuckerberg to agree to announce the gift on “The Oprah Winfrey Show,” timed to coincide with the début of the documentary “Waiting for ‘Superman,’ ” and its major marketing campaign. The film chronicled families’ desperate efforts to get children out of failing traditional public schools and into charters, and blamed the crisis largely on teachers’ unions.

Sheryl Sandberg, who vetted the agreement for Zuckerberg, e-mailed updates to Booker’s chief fund-raiser, Bari Mattes: “Mark is following up with Gates this week. I will call David Einhorn”—a hedge-fund manager—“this week (my cousin). Mark is scheduling dinner with Broad. . . . AMAZING if Oprah will donate herself? Will she? I am following up with John Doerr/NewSchools Venture Fund.” Doerr is a venture capitalist.

Ray Chambers, a Newark native who made a fortune in private equity and for decades had donated generously to education, learned of the deal and offered to coördinate a million-dollar gift from local philanthropies as a show of community support. But Mattes wrote to Booker in an e-mail, “I wouldn’t bother. $1 M as a collective gift over 5 years is just too insignificant for this group.” The e-mails were obtained by the A.C.L.U. of New Jersey.

On September 24, 2010, the team described their plan for Newark on “Oprah.” “So, Mr. Zuckerberg,” Oprah asked, “what role are you playing in all of this?” He replied, “I’ve committed to starting the Startup:Education Foundation, whose first project will be a one-hundred-million-dollar challenge grant.” Winfrey interrupted: “One. Hundred. Million. Dollars?” The audience delivered a standing ovation. When Winfrey asked Zuckerberg why he’d chosen Newark, he gestured toward Booker and Christie and said, “Newark is really just because I believe in these guys. . . . We’re setting up a one-hundred-million-dollar challenge grant so that Mayor Booker and Governor Christie can have the flexibility they need to . . . turn Newark into a symbol of educational excellence for the whole nation.” This was the first that Newark parents and teachers had heard about the revolution coming to their schools.

Zuckerberg knew that there had been resistance to education reform in other cities, particularly in Washington, D.C., where voters had rebelled against the schools chancellor Michelle Rhee’s autocratic leadership and driven Mayor Adrian Fenty from office. But he was confident that Booker, twice elected by wide margins, had the city behind him. On the day of the “Oprah” announcement, Zuckerberg posted a note on his Facebook page saying that Booker would focus as single-mindedly on education in his second term as he had on crime in his first.

A very different picture of Newark appeared, however, in the daily reports of the Star-Ledger. The city was experiencing its bloodiest summer in twenty years. As Booker negotiated the Zuckerberg gift, he was facing a potentially ruinous deficit, aggravated by the recession. He was laying off a quarter of the city’s workforce, including a hundred and sixty-seven police officers—almost every new recruit hired in his first term. The city council was in revolt over Booker’s bid to borrow heavily from the bond market to repair a failing water system. Meanwhile, he was managing a busy speaking schedule, which frequently took him out of the city. Disclosure forms show $1,327,190 in revenue for ninety-six speeches given between 2008 and May, 2013. “There’s no such thing as a rock-star mayor,” the historian Clement Price, of Rutgers University, told me. “You can be a rock star or you can be a mayor. You can’t be both.”

Three days after “Oprah,” Booker appeared on MSNBC’s “Morning Joe” with Christie and Arne Duncan, and vowed, “We have to let Newark lead and not let people drop in from outside and point the way.” But Newark wasn’t leading. As matching dollars were pledged, Zuckerberg’s gift moved from his foundation, in Palo Alto, into the new Foundation for Newark’s Future, in Newark. F.N.F.’s board included the Mayor and those donors who contributed ten million dollars or more. (The figure was later reduced to five million, still far beyond the budget of local foundations.) F.N.F. agreed to appoint a community advisory board, but it wasn’t named for another two years, and by then most of the money was committed—primarily to new labor contracts and to the expansion and support of charter schools. In one of the foundation’s first expenditures, it paid Tusk Strategies, in New York, $1.3 million to manage the community-engagement campaign. Its centerpiece was ten public forums in which residents were invited to make suggestions to improve the schools. Bradley Tusk had managed Michael Bloomberg’s 2009 reëlection campaign and was a consultant to charter schools in New York.

Hundreds of residents came to the first few forums and demanded to be informed and involved. People volunteered to serve as mentors for children who lacked adult support. Shareef Austin, a recreation director at Newark’s West Side Park, said, “I have kids every day in my program, their homes are broken by crack. Tears come out of my eyes at night worrying about them. If you haven’t been here and grown up through this, you can’t help the way we can.” Calvin Souder, a lawyer who taught for five years at Barringer High while he was in law school, said that some of his most challenging students were the children of former classmates who had dropped out of school and joined gangs.

Austin said that he and others who volunteered to help were never contacted: “I guess those ideas look little to the people at the top, but they’re big to us, because we know what it can mean to the kids.”

Booker participated in several of the meetings. He was excited to hear principals asking for more autonomy—one of his goals. He told one crowd, “It’s destiny that we become the first city in America that makes its whole district a system of excellence. We want to go from islands of excellence to a hemisphere of hope.”

Meanwhile, teachers worried about their students’ bleak horizons. David Ganz devised a poetry exercise for his all-boys freshman literacy class at Central High School. He put the word “hope” on the board and gave students a few minutes to write. Fourteen-year-old Tyler read his poem to the class:

We hope to live,

Live long enough to have kids

We hope to make it home every day

We hope we’re not the next target to get sprayed. . . .

We hope never to end up in Newark’s dead pool

I hope, you hope, we all hope.

Another student, Mark, wrote, “My mother has hope that I won’t fall victim to the streets. / I hope that hope finds me.” And Tariq wrote, “Hope—that’s one thing I don’t have.”

Booker asked Christopher Cerf, his longtime unofficial education adviser, to plan the overhaul. Cerf, then fifty-six, had become a central switching station for the education-reform movement. Until 2005, he led Edison Schools, a for-profit manager of public schools. He attended Eli Broad’s management training program for public-school leaders. In 2006, he became chief deputy to the New York schools chancellor, Joel Klein, sometimes called the “granddaddy of reform.” For the Newark project, Cerf created a consulting firm, Global Education Advisers. Booker solicited grants from the Broad Foundation and Goldman Sachs, to begin paying the firm.

Cerf set out to develop a “fact base” of Newark’s financial, staffing, and accountability systems so that a new superintendent could move swiftly to make changes. He explained to me, “My specialty is system reform—micro-politics, selfishness, corruption, old customs unmoored from any clear objectives.” Ultimately, Zuckerberg and matching donors paid the firm and its consultants $2.8 million, although Cerf emphasized that he personally accepted no pay, and he left the firm in December, 2010. That month, Christie chose Cerf to be New Jersey’s education commissioner, which meant that the district’s chief consultant went on to become its chief overseer.

Speaking to representatives of Newark’s venture philanthropists, Cerf said, “I’m very firmly of the view that when a system is as broken as this one you cannot fix it by doing the same things you’ve always done, only better.” It was time for “whole district reform.” Newark presented a unique opportunity. The district, Cerf said, “is manageable in size, it’s led by an extraordinary mayor, and it’s managed by the state. We still control all the levers.” With no superintendent in place, Cerf’s office effectively ran the schools, with the consultants providing technical support.

During the next two years, more than twenty million dollars of Zuckerberg’s gift and matching donations went to consulting firms with various specialties: public relations, human resources, communications, data analysis, teacher evaluation. Many of the consultants had worked for Joel Klein, Teach for America, and other programs in the tight-knit reform movement, and a number of them had contracts with several school systems financed by Race to the Top grants and venture philanthropy. The going rate for individual consultants in Newark was a thousand dollars a day. Vivian Cox Fraser, the president of the Urban League of Essex County, observed, “Everybody’s getting paid, but Raheem still can’t read.”

II. THE OPPOSITION

In February, 2011, the Star-Ledger obtained a confidential draft of recommendations by Global Education Advisers that contained a scenario to close or consolidate eleven of the lowest-performing district schools, and to make way for charters and five themed public high schools, to be funded by the Foundation for Newark’s Future. The newspaper ran a front-page article listing the schools likely to be affected and disclosed that Cerf, the state commissioner, had founded the consulting firm.

Newark’s school advisory board happened to be meeting the night the article was published. The board has no real power, since it’s under state control, and meetings were normally sleepy and sparsely attended. Teachers’ union leaders had been poised to attack the reform effort, and that evening more than six hundred parents and union activists showed up. One mother shouted, “We not having no wealthy white people coming in here destroying our kids!” From aisles and balconies, people yelled, “Where’s Christie!” “Where’s Mayor Hollywood!” The main item on the agenda—a report by the Newark schools’ facilities director on a hundred and forty million dollars spent in state construction funds, with little to show for it—reinforced people’s conviction that someone was making a killing at their children’s expense. “Where’d the money go? Where’d the money go?” the crowd chanted.

On a Saturday morning later that month, Booker and Cerf met privately on the Rutgers-Newark campus with twenty civic leaders who had hoped that the Zuckerberg gift would unite the city in the goal of improving the schools. Now they had serious doubts. “It’s as if you guys are going out of your way to foment the most opposition possible,” Richard Cammarieri, a former school-board member who worked for a community-development organization, told them.

Booker acknowledged the missteps, but said that he had to move quickly. He and Christie could be out of office within three years. If a Democrat defeated Christie in 2013, he or she would have the backing of the teachers’ unions and might return the district to local control. “We want to do as much as possible right away,” Booker said. “Entrenched forces are very invested in resisting choices we’re making around a one-billion-dollar budget.” Participants in the meeting, who had worked for decades in Newark, were doubtful that reforms imposed over three years would be sustainable.

Cerf said his motives were altruistic: “Public education embodies the noble ideal of equal opportunity. I know equal opportunity was a massive lie. It’s a lie in Newark, in New York, in inner cities across the country. Call me a nut, but I am committing my life to try to fix that.” He and Booker pledged to engage Newark residents, and Booker asked the group of civic leaders for their public support. “If the purpose is right for kids, I’m willing to go down in a blaze of glory,” he said, leaning over the table with both fists clenched.

Ras Baraka, the principal of Central High School and a city councilman, emerged as the leading opponent of change. His father, Amiri Baraka, was the most prominent radical voice in recent Newark history. Ras Baraka delivered speeches in the style of a street preacher, rousing Newark’s dispossessed as forcefully as Booker inspired philanthropists. The Booker-Christie-Zuckerberg strategy was doomed, he said, since it included no systemic assault on poverty. He told his students that Christie needed them to fail so that he could close Central High and turn it over to charters. “Co-location is more like colonization,” he said of placing charters in unused space inside district schools. Powerful interests wanted the district’s billion dollars.

Many reformers saw Baraka as the symbol of all that ailed urban education. Like a number of New Jersey politicians, he held two public jobs, and he earned more than two hundred thousand dollars a year. His brother was on his city-council payroll. Central High had abysmal scores on the proficiency exam in 2010, Baraka’s first year as principal, and it was in danger of being closed under the federal No Child Left Behind law. But Baraka mounted an aggressive turnaround strategy, using some of the reformers’ techniques. “I stole ideas from everywhere,” he told me. With a federal school-improvement grant, he extended the school day, introduced small learning academies, greatly intensified test prep, and hired consultants to improve literacy instruction. He also summoned gang members who had roamed the halls with impunity for years and told them their battles had to stop at the school door. Students anointed him B-Rak.

Still, results were mixed. In 2011, Central’s proficiency scores rose dramatically, and Cerf spoke at an assembly to congratulate the students. But only five per cent of Central students qualified as “college ready” in reading, based on their A.C.T. scores.

In private, Baraka supported many of the reformers’ critiques of the status quo, including revoking tenure for teachers with the lowest evalutions. Although he publicly embraced the unions’ positions, he told me he opposed paying teachers based on seniority and degrees, as Newark did under its union contract. “We should make a base pay, and the only way to go up is based on student performance,” he said. He told me that many in Newark quietly agreed. But, he insisted, “this dictatorial bullying is a surefire way to get people to say, ‘No, get out of here.’ ” He laughed. “They talk about ‘Waiting for “Superman.” ’ Well, Superman is not real. Did you know that? And neither is his enemy.”

In 2011, Booker paid a visit to SPARK Academy, a charter elementary school run by Newark’s KIPP network. He was accompanied by Cari Tuna, the girlfriend (now the wife) of Facebook’s co-founder, the billionaire Dustin Moskovitz. Booker wanted her to witness the teachers’ intensive training program. Tuna and Moskovitz had started their own foundation, and Booker hoped they would help match Zuckerberg’s hundred million dollars. (They later pledged five million dollars.) SPARKhad recently moved to George Washington Carver Elementary School, taking over the third floor. Carver was in one of the most violent neighborhoods in Newark. Joanna Belcher, the SPARK principal, asked the Mayor to give the teachers a talk on the “K” in SPARK, which stands for “keep going.” Booker invoked the Selma march for voting rights, in 1965, and thanked the SPARK teachers for advancing the cause—“freedom from the worst form of bondage in humanity, imprisonment in ignorance.” (My son later took a teaching job at a KIPP school in New York.)

Disagreements over school reform tended to center on resources shifting from traditional public schools to charter schools. When students moved to charters, public money went with them. The battle often intensified when spare classroom space in district schools was turned over to charters, with their extra resources and freedom to hire the best teachers. But Belcher and her staff developed a close working relationship with Carver’s principal, Winston Jackson. They were alarmed that Carver, whose students had among the lowest reading scores in the city, had for years been a dumping ground for weak teachers. Several SPARK teachers asked Booker what he planned to do for children who occupied the other floors of the building.

“I’ll be very frank,” Booker said. “I want you to expand as fast as you can. But, when schools are failing, I don’t think pouring new wine into old skins is the way. We need to close them and start new ones.”

Jackson had never got the police to respond adequately to his pleas for improved security. Gangs periodically held nighttime rites on school grounds, and Jackson reported them without result. One night, a month after SPARK settled into Carver, a security camera captured images of nine young men apparently mauling another. When Jackson and Belcher arrived the next morning, they found bloody handprints on the wall and blood on the walkway. His and Belcher’s calls to police and e-mails to the superintendent’s staff went unanswered. At Jackson’s request, Belcher e-mailed the Mayor, attaching three pictures of the bloody trail on “the steps our K-2 scholars use to enter the building.” Twenty minutes later, Booker responded: “Joanna, your email greatly concerned me. I have copied this email to the police director who will contact you as soon as possible. Cory.” The police director, Sam DeMaio, called, and the precinct captain and the anti-gang unit visited the school. Police presence was stepped up, and the gang moved on.

III. POT OF GOLD

Zuckerberg and Sandberg were increasingly concerned. Six months after the announcement on “Oprah,” Booker and Christie had no superintendent, no comprehensive reform plan, and no progress toward a new teachers’ contract. On Saturday, April 2, 2011, they met with Booker at Facebook’s headquarters, in Palo Alto. If these are the wrong metrics for measuring progress, they asked, what are the right ones? They were holding Booker accountable for performance, just as he intended to hold teachers and principals accountable. Booker was contrite. “Guilty as charged,” he replied.

Zuckerberg urged him to find a strong superintendent quickly, and after the meeting he sent him one of Facebook’s motivational posters: “DONE IS BETTER THAN PERFECT.” Booker, Christie, and Zuckerberg had tried to recruit John King, at that time the Deputy Commissioner of Education for New York State, who had led some of the most successful charter schools in Boston and New York City, but he had turned down the job. According to several of his friends, King worried that everyone involved was underestimating how long the work would take. One of them recalled him saying, “No one has achieved what they’re trying to achieve—build an urban school district serving high-poverty kids that gets uniformly strong outcomes.” He had questions about a five-year plan overseen by politicians who were likely to seek higher office.

After Booker returned from California, Cami Anderson emerged as the leading candidate. Thirty-nine years old, she was the daughter of a child-welfare advocate and the community-development director for the Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley. She had spent her entire career in reform circles. She’d taught in Wendy Kopp’s Teach for America, then joined her executive team in New York. Anderson later worked at New Leaders for New Schools, which trained principals as reform leaders. One of its founders, Jon Schnur, became an architect of Race to the Top. She’d been a senior strategist for Booker’s 2002 mayoral campaign and had been superintendent of alternative high schools under Joel Klein, in New York.

Anderson had two apparent marks against her: she was white and she was known for an uncompromising management style. Since 1973, Newark had had only African-American superintendents. But Anderson had an interesting backstory. She often mentioned that she had grown up with nine adopted siblings who were black and brown. Her partner, Jared Robinson, is African-American, and their son is named after Frederick Douglass. As for her methods, her friend Rebecca Donner, a novelist, said, “She has her own vision and she won’t stop at anything to realize it. If you’re faint of heart, if you’re easily cowed, if you disagree with her, you’re going to feel intimidated.” Cerf and Booker came to see that as a virtue. As Cerf put it, “Nobody gets anywhere in this business unless you’re willing to get the shit absolutely kicked out of you and keep going. That’s Cami.”

Christie appointed Anderson in May, 2011. It quickly emerged that she differed with her bosses about the role of charter schools in urban districts. She pointed out that, with rare exceptions, charters served a smaller proportion than the district schools of children who lived in extreme poverty, had learning disabilities, or struggled to speak English. Moreover, charter lotteries disproportionately attracted the “choosers”—parents with the time to navigate the process. Charters in Newark were expected to enroll forty per cent of the city’s children by 2016. That would leave the neediest sixty per cent in district schools. Booker, Christie, and Zuckerberg expected Anderson to revive the district, yet as children and revenue were siphoned off she would have to close schools and dismiss teachers. Because of the state’s seniority rules, the most junior teachers would go first. Anderson called this “the lifeboat theory of education reform,” arguing that it could leave a majority of children to sink as if on the Titanic. “Your theories of change are on a collision course,” she told Cerf and Booker. As Anderson put it to me, “I told the Governor . . . I did not come here to phase the district out.”

Anderson acknowledged the successes of the top charter schools, but Newark faced the conundrum common to almost every urban school system: how to expand charters without destabilizing traditional public schools. Christie and Booker agreed to her request for time to work on a solution, even though Zuckerberg and other donors had already committed tens of millions of dollars to expand charters.

Anderson turned her immediate attention to the district’s schools. She gave principals more flexibility and introduced new curricula aligned to the Common Core standards. Using $1.8 million from the Foundation for Newark’s Future, she hired the nonprofit consulting group TNTP, in part to develop more rigorous evaluation systems. In her first year, the foundation gave her a four-million-dollar grant to hire consultants at her own discretion.

One of her prime initiatives in her first two years was to close and consolidate the twelve lowest-performing kindergarten-through-eighth-grade schools into eight “renew schools.” Each was assigned a principal who, borrowing from the charter model, would choose his or her own teaching staff. The schools also got math and literacy coaches and smart boards, along with the new curricula. Teachers worked an extended day and two extra weeks in the summer. Anderson intended to create “proof points” that would show how to turn around failing district schools.

The eight consolidated schools opened in the fall of 2012, and most won strong support from parents. At the hundred-year-old Peshine Avenue School, in the South Ward, Chaleeta Barnes, the new principal, and Tameshone Lewis, the vice-principal, both had deep Newark roots, and parents, teachers, and children responded well to their insistence on higher standards. They replaced more than half the previous year’s teachers, and the new staff coördinated efforts to improve instruction and address individual students’ academic and discipline issues.

Teachers worked closely with children who couldn’t keep up, and many of them saw improvement, but the effects of children’s traumas outside school posed bigger problems. The father of a student in Shakel Nelson’s fifth-grade math class had been murdered early in the school year. When Nelson sat beside his desk and encouraged him, he sometimes solved problems, but as she moved on he put his head down and dropped his pencil. A girl who was excelling early in the year stopped trying when her estranged, emotionally disturbed parents resumed contact and began fighting.

The quality of teaching and the morale in most of the renew schools improved, but only Peshine made modest gains in both math and literacy on state tests. Six others declined in one subject or both, and the seventh remained unchanged in one and increased in one. This wasn’t surprising. It takes more than a year for reforms to take hold and show up in test scores. Across the district, in Anderson’s first two years, the percentage of students passing the state’s standardized tests declined in all but two of the tested grades. She questioned the validity of the tests, saying that they had become harder and the students needier, although she used them to determine which schools were failing and required overhaul. After her first year, she announced a ten-per-cent gain in the high-school graduation rate, but A.C.T. scores indicated that only two per cent of juniors were prepared for college.

Anderson recognized that the schools needed more social and emotional support, but pointed out that Newark already spent more money per student than almost every other district in the country. She urged principals to shift their existing budgets accordingly. “There’s no pot of gold,” she said.

In fact, there was a pot of gold, but much of it wasn’t reaching students. That was the reformers’ main argument against the wasteful administrations of urban schools. More than half of the Newark district’s annual budget paid for services other than instruction—often at inordinate prices. Charter schools received less public money per pupil, but, with leaner bureaucracies, more dollars reached the classroom. SPARK’s five hundred and twenty students were needier than those in most Newark charters. To support them, the principal, Joanna Belcher, placed two teachers in each kindergarten class and in each math and literacy class in grades one through three. Peshine could afford only one in each. SPARK also had more tutors and twice as many social workers, who provided weekly counselling for sixty-five children. Last year, SPARK’s inaugural class took New Jersey’s third-grade standardized tests. Eighty-three per cent passed in language arts and eighty-seven per cent in math, outscoring the district by almost forty points in each.

Reformers also argued that teachers must be paid according to competency. “Abolish seniority as a factor in all personnel decisions,” Zuckerberg wrote in September, 2010, in a summary of his agreement with Booker. Tenure and seniority protections were written into state law, so the negotiations took place both in the legislature and at the bargaining table. After arduous talks with the state teachers’ union—the biggest contributor to New Jersey politicians—a major reform measure was passed that made tenure harder to achieve and much easier to revoke. But, in return for union support, the legislature left seniority protections untouched.

Soon afterward, in November, 2012, the Newark Teachers Union agreed to a new contract that, for the first time, awarded raises only to teachers rated effective or better under the district’s rigorous new evaluation system. Those who got the top rating would receive merit bonuses of between five thousand and twelve thousand five hundred dollars.

All of this came at a steep price. The union demanded thirty-one million dollars in back pay for the two years that teachers had worked without raises—more than five times what top teachers would receive in merit bonuses under the three-year contract. Zuckerberg covered the expense, knowing that other investors would find the concession unpalatable. The total cost of the contract was about fifty million dollars. The Foundation for Newark’s Future also agreed to Anderson’s request to set aside another forty million dollars for a principals’ contract and other labor expenses. Zuckerberg had hoped that promising new teachers would move quickly up the pay scale, but the district couldn’t afford that along with the salaries of veteran teachers, of whom five hundred and sixty earned more than ninety-two thousand dollars a year. A new teacher consistently rated effective would have to work nine years before making sixty thousand dollars.

The seniority protections proved even more costly. School closings and other personnel moves had left the district with three hundred and fifty teachers that the renew principals hadn’t selected. If Anderson simply laid them off, those with seniority could “bump” junior colleagues. She said this would have a “catastrophic effect” on student achievement: “Kids have only one year in third grade.” She kept them all on at full pay, at more than fifty million dollars over two years, according to testimony at the 2013 budget hearing, assigning them support duties in schools. Principals with younger staffs were grateful. Far fewer of the teachers left than Anderson had anticipated. She hoped Christie would grant her a waiver from the seniority law, allowing her to lay off the lowest-rated teachers, a move that both the legislature and the national teachers’ union promised to fight.

Improbably, a district with a billion dollars in revenue and two hundred million dollars in philanthropy was going broke. Anderson announced a fifty-seven-million-dollar budget gap in March, 2013, attributing it mostly to the charter exodus. She cut more than eighteen million dollars from school budgets and laid off more than two hundred attendance counsellors, clerical workers, and janitors, most of them Newark residents with few comparable job prospects. “We’re raising the poverty level in Newark in the name of school reform,” she lamented to a group of funders. “It’s a hard thing to wrestle with.”

School employees’ unions, community leaders, and parents decried the budget cuts, the layoffs, and the announcement of more school closings. Anderson’s management style didn’t help. At the annual budget hearing, when the school advisory board pressed for details about which positions and services were being eliminated in schools, her representatives said the information wasn’t available. Anderson’s budget underestimated the cost of the redundant teachers by half.

The board voted down her budget and soon afterward gave a vote of no confidence—unanimously, in both cases, but without effect, given their advisory status. At about the same time, Ras Baraka declared his candidacy for mayor, vowing to “take back Newark” from the control of outsiders. He made Anderson a prime target. “We are witnessing a school-reform process that is not about reforming schools,” he told a packed auditorium in his South Ward district. He gave no hint that although he detested the reformers’ tactics, he shared a number of their goals.

In May, with Baraka leading the charge, the city council unanimously passed a resolution calling for a moratorium on all Anderson’s initiatives until she produced evidence that they raised student achievement. Later that month, Anderson sent a deputy to ask Baraka to take a leave of absence as principal of Central High. She argued that he had a conflict of interest: as a mayoral candidate, he was opposing initiatives that he was obliged to carry out as a principal. He refused, and a video of his defiant account of the incident was e-mailed to supporters with the question “Are we all going to stand by like chumps, and allow this ‘Interloping Outsider’ to harass one of our own?”

Hundreds of Baraka’s supporters, including union leaders and activists, attended a school-board meeting that month, to defend him and to denounce Anderson. Her assistant superintendent asked renew-school leaders and parents to testify at the meeting. As Peshine parents and teachers spoke, Anderson’s opponents held aloft signs saying “Paid for by Cami Anderson.” A Peshine teacher confronted Donna Jackson, an activist and perennial detractor of Booker and Anderson, asking why she would deride Newark teachers who were helping children. “I’m sick of hearing these good things about Peshine,” she said. “That just gives Cami an excuse to close more schools.”

On September 4, 2013, Christie said he planned to reappoint Anderson when her term expired, at the end of the school year: “I don’t care about the community criticism. We run the school district in Newark, not them.” But Anderson was increasingly on her own. Christie was campaigning for reëlection and laying the groundwork for a Presidential campaign. Booker was running for the Senate in a special election to replace the late Frank Lautenberg. Six weeks later, he won, and left for Washington.

Many reformers were unhappy with Anderson, too. They objected to her postponement of the dramatic expansion of charter schools that Booker had promised, saying she was denying children the chance for a better education.

IV. ONE NEWARK

Anderson spent much of the fall working with data analysts from the Parthenon Group, an international consulting firm that received roughly three million dollars over two years from Newark philanthropy. She wanted to come up with a plan that would resolve the overlapping complexities of urban schooling. How could she insure that charters, as they expanded, enrolled a representative share of Newark’s neediest children? How could district schools be improved fast enough to persuade families to stick with them? How could she close schools without devastating effects on the neighborhoods? How could she retain the best teachers, given that, by her estimate, she would have to lay off a thousand teachers in the next three years? “This is sixteen-dimensional chess,” she said.

She called her plan One Newark. Rather than students being assigned to neighborhood schools, families would choose among fifty-five district schools and sixteen charter schools. An algorithm would give preference to students from the lowest-income families and those with special needs. In a major accomplishment for Anderson, sixteen of twenty-one charter organizations had agreed to participate, in the name of reducing selection bias. Of the four neighborhood elementary schools in the South Ward slated to close, three were to be taken over by charters, and the fourth would become an early-childhood center. In all, more than a third of Newark’s schools would be closed, renewed, relocated, phased out, repurposed, or redesigned. Beginning in early January, thousands of students would need to apply to go elsewhere. Anderson said that the entire plan had to be enacted; removing any piece of it would jeopardize the whole, and hurt children.

In the fall, she held dozens of meetings explaining the rationale for One Newark to charter-school leaders, business executives, officials of local foundations, elected officials, clergy, and civic leaders. But participants said she didn’t present the specific solutions, because they weren’t yet available. Similarly, parents learned in the fall that their schools might be closed or renewed, but they would not get details until December. During the week before the Christmas vacation, Anderson sent her deputies to hastily scheduled school meetings to release the full plan to parents. She anticipated an uproar—“December-palooza,” she called it to her staff—which she hoped would diminish by January.

Instead, parents demanded answers and didn’t get them. Anderson said that students with learning disabilities would be accommodated at all district schools, but the programs hadn’t yet been developed. Families without cars asked how their children would get to better schools across town, since the plan didn’t provide transportation. Although Anderson initially announced that charters would take over a number of K-8 schools, it turned out that the charters agreed to serve only K-4; children in grades five through eight would have to go elsewhere.

The biggest concern was children’s safety, particularly in the South Ward, where murders had risen by seventy per cent in the past four years. The closest alternative to Hawthorne Avenue School, which was losing its fifth through eighth grades, was George Washington Carver, half a mile to the south. Jacqueline Edward and Denise Perry-Miller, who have children at Hawthorne, knew the dangers well. Gangs had tried to take over their homes, tearing out pipes, sinks, and boilers, and stealing their belongings, forcing both families temporarily into homeless shelters. Edward and Perry-Miller took me on a walk along the route to Carver. We crossed a busy thoroughfare over I-78, then turned onto Wolcott Terrace, a street with several boarded-up houses used by drug dealers.

Edward said, “I will not allow my daughter to make this walk. My twenty-eight-year-old started off in a gang, and we fought to get him out. My twenty-two-year-old has a lot of anger issues because Daddy wasn’t there. I just refuse to see another generation go that way.” Then, as if addressing Anderson, she asked, “Can you guarantee me my daughter’s safety? . . . Did you think this through with our children in mind or did you just do this to try to force us to leave because big business wants us out of here?” Anderson told me that she will address all safety issues, either with school buses or by accommodating middle-schoolers in their neighborhoods. Hawthorne parents said they had not heard this.

Shavar Jeffries, Baraka’s thirty-nine-year-old opponent in the mayoral election, to be held May 13th, could have been a key ally for Anderson. He was a member of the school advisory board when she arrived, and supported most of her agenda, including the expansion of charter schools and reforms in district schools. But he was also a strong opponent of state control, and he challenged her publicly a number of times, saying she had not shared enough information with the board. He was among those who voted against her 2013 budget. Afterward, according to former aides to Anderson, she told potential donors to his campaign that he was not a real reformer, citing his vote against her budget. (Anderson denied saying this.)

He believed that public schools and charter schools could work in tandem and that education reform could take hold in Newark, but only if residents’ voices were heard and respected. “Our superintendent, unfortunately, has in recent times run roughshod over our community’s fundamental interests,” he said in a campaign speech on education. “I say this as a father of two: no one is ever going to do anything that’s going to affect my babies without coming to talk to me.”

The day after the release of One Newark, Ras Baraka held a press conference in front of Weequahic High School, denouncing the plan as “a dismantling of public education.… It needs to be halted.” Enrollment at Weequahic was plummeting, and Anderson intended to phase it out over three years, moving a new all-girls and an all-boys academy into the building. Weequahic was the alma mater of the long-decamped Jewish community and of thousands of Newark community leaders, politicians, athletes, and teachers, who were protesting vociferously. Photos and video footage of Baraka in front of the building, which has a famous W.P.A. mural—the “Enlightenment of Man”—appeared in newspapers, on television, and on blogs and Web sites. “You could feel a shift in the momentum on that day,” Bruno Tedeschi, a political strategist, told me. “I said to myself, ‘He’s trying to turn the election into a referendum on her. From this point on, it doesn’t matter what she does.’ She’s a symbol of Christie and the power structure that refuses to give Newark what it feels rightly entitled to.” Civic leaders and clergy, whom she expected to endorse the plan, backed off. Several weeks later, Anderson agreed to keep Weequahic intact for at least two years.

Christie met with Anderson in Trenton in late December and promised to support her no matter how vocal the opposition. But two weeks later the Bridgegate scandal broke, and Christie had his own career to consider. Anderson moved out of Newark, telling friends she feared for her family’s safety.

On January 15th, at the Hopewell Baptist Church, Baraka held a rally for people affected by One Newark. Four principals of elementary schools in the South Ward argued that deep staff cuts over four years had made failure inevitable. Anderson suspended them, and instructed her personnel staff to investigate whether the principals were thwarting enrollment in One Newark. The move set off such a furor that Joe Carter, the pastor of the New Hope Baptist Church, told Christie he feared civil unrest. Christie told Cerf to get a handle on the matter, and within a week Anderson lifted the suspensions. The principals have since filed a federal civil-rights case alleging violation of their freedom of speech.

In late January, Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, spoke at a school-board meeting at First Avenue School in Newark. Five hundred people filled the auditorium; another three hundred and fifty listened in the cafeteria, and more than a hundred stood outside, demanding entry. Weingarten pledged the A.F.T.’s support “until this community gets its schools back,” and declared, “The nation is watching Newark.” Baraka demanded Anderson’s immediate removal, prompting the crowd to cheer and chant “Cami’s gotta go!” as they hurled invective and waved signs reading “Cami, Christie, stop the bullying!”

Then the mother of an honor-roll student at Newark Vocational High School, which Anderson planned to close, stood up and demanded of her, “Do you not want for your brown babies what we want for ours?” She said that Anderson “had to get off East Kinney because too many of us knew where you were going.” Anderson reddened, shook her head, and said again and again, “Not my family!” Moments later, she gathered her papers and left. She has not attended a school-board meeting since. “The dysfunction displayed within this forum sets a bad example for our children,” she wrote in a statement distributed by the district. Antoinette Baskerville-Richardson, who was the board president at the time, responded, “You own this situation. For the third year in a row, you have forced your plans on the Newark community, without the measure of stakeholder input that anyone, lay or professional, would consider adequate or respectful.”

“This is the post-Booker era,” Ras Baraka said recently at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, in downtown Newark. “The stage has been set, the lights are on, people are in the theatre—it’s time for us to perform.” He was speaking about this week’s mayoral election, which he was favored to win, but he could have been describing the city’s battle over education. Baraka is heavily backed by education workers’ unions, and Jeffries by the school-reform movement. Booker has maintained a public silence about the Newark schools since being sworn in as a senator. Christie has been trying to salvage his Presidential prospects. Almost all of Zuckerberg’s hundred million dollars has been spent or committed. He and Chan gave almost a billion dollars to a Silicon Valley foundation to go toward unspecified future gifts, but they have not proceeded with reforms in other school districts, as originally planned. Cerf left his job as New Jersey’s education commissioner in March to join Joel Klein, who, in 2010, had resigned as New York schools chancellor to run Rupert Murdoch’s new education-technology division at News Corp. Anderson declined to say whether she had signed a new three-year contract. She said that she could have done more to engage the community, but she’d worried that the process would be coöpted by “political forces whose objective is to create disruption.” Nor could she vet the plan as it evolved with individual families. “That is the nature of sixteen-dimensional chess,” she said. “You can’t create concessions in one place that then create problems in another.”

Across the country, the conversation about reform is beginning to change. On April 30th, the NewSchools Venture Fund, a nonprofit venture-philanthropy firm, which donated ten million dollars to the Newark effort, held its annual summit for the education-reform movement. “The people we serve have to be a part of their own liberation,” Kaya Henderson, the successor to Michelle Rhee, in Washington, D.C., said. James Shelton, Arne Duncan’s deputy at the Department of Education, acknowledged the need for more racial diversity among those making the decisions. “Who in here has heard the phrase that education is the civil-rights movement of our age?” he asked. “If we believe that, then we have to believe that the rest of the movement has to come with it.”

In Newark, the solutions may be closer than either side acknowledges. They begin with getting public-education revenue to the children who need it most, so that district teachers can provide the same level of support that SPARK does. And charter schools, given their rapid expansion, need to serve all students equally. Anderson understood this, but she, Cerf, Booker, and the venture philanthropists—despite millions of dollars spent on community engagement—have yet to hold tough, open conversations with the people of Newark about exactly how much money the district has, where it is going, and what students aren’t getting as a result. Nor have they acknowledged how much of the philanthropy went to consultants who came from the inner circle of the education-reform movement.

Shavar Jeffries believes that the Newark backlash could have been avoided. Too often, he said, “education reform . . . comes across as colonial to people who’ve been here for decades. It’s very missionary, imposed, done to people rather than in coöperation with people.” Some reformers have told him that unions and machine politicians will always dominate turnout in school-board elections and thus control the public schools. He disagrees: “This is a democracy. A majority of people support these ideas. You have to build coalitions and educate and advocate.” As he put it to me at the outset of the reform initiative, “This remains the United States. At some time, you have to persuade people.” ♦

Don Rojas,

Director of Communications,

Institute of the Black World 21st Century (IBW),

51 Millstone Road,

Randallstown, MD 21133

Ph: 410-844-1031

Web: www.ibw21.org