As one who for over half a century has actively tried to engage in the political process in order to empower African descendant peoples, I now find myself asking the question “what ever happened to Black Power”? I have been around long enough “to remember when”. I remember when there existed in Black communities a spirit that spoke to collective interests and common concerns. This was something beyond what the sociologists simply characterize as “community”.

The Black community was virtually regarded by all of its constituents as sacred territory. The community was neither to be fouled nor abused. Without formal pronouncements, the folkways of the community established and defined the norms of behavior. The behaviors of young folks in the community suggested that they were, in fact, modeling the behaviors of the age group in front of them. Generally speaking, everyone was consciously concerned with being a good member of the community. This spirit prevailed even while we as young people did “young people’s stuff”.

The Black community was virtually regarded by all of its constituents as sacred territory. The community was neither to be fouled nor abused. Without formal pronouncements, the folkways of the community established and defined the norms of behavior. The behaviors of young folks in the community suggested that they were, in fact, modeling the behaviors of the age group in front of them. Generally speaking, everyone was consciously concerned with being a good member of the community. This spirit prevailed even while we as young people did “young people’s stuff”.

Black Power Has Always Been A Reality: Long Before It Was Named

My community was predominantly a working class community. In spite of that general designation, the doctors, “the undertakers”, the dentists and “the lawyer” lived among us. They provided for many of us the visual inspiration to do more and importantly to be more. This is not a hyperbolic description of life in a black community in central New Jersey in the 1940’s and 50’s. In those days, even the criminals would insure that all heavy criminal activity would be conducted “outside of the community” and everyone was a guardian of the elderly. This was the essence of “Black Power”, before it was so named. It existed long before the term was coined. “Black Power” was Black people working in relative solidarity and in concert with one another for the good of the whole. Addicted to the best logic of the human spirit our shoulder was “to the wheel” as we harbored the belief that we could make a way out of no way and build solid futures employing the principles that some of us would later adopt as the foundational principles of Kwanzaa. I am not so naive as to believe that my home town in central New Jersey was the universal experience reflecting Black life in America during this period of time. Regular family visits to the South, while growing up, made the inequity in the opportunity structure patently clear. Nevertheless, there existed a spirit of connection that superseded the geographical differences. When I moved permanently to the South at the end of the last century, community elders still existed who talked about “slavery times”.

The Historical Black Community Spawned the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement To Eliminate Policies and Practices That Oppressed Black People

The reference to slavery times was not to the slavery of the antebellum South, it was instead the slavery of post-Civil War reconstruction and “Jim crow” policies. It was the legal political and economic conditions that for centuries had served to debilitate and openly restrict Black life in America, well into the 1970’s and beyond. What makes their story so remarkable, in retrospect, is the fact that in spite of the oppression, and the legal and physical intimidation, it was this cohort of ordinary Black America that simply got tired of being sick and tired and who corralled the racial pride, the community solidarity and collective consciousness to create one of the most effective movements, to date, for the transformation of American society.

It must not be forgotten, that it was primarily this historical experience and the movement for social and political equality that spawned and then introduced the modern Civil Rights Movement. This was, in fact, Black Power. The Chapters in that history, that would become known as the Black Power Movement, was yet to be conceived. We had it long before we named it. Although the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement were both pro Black in orientation and architectural design, neither was philosophically anti-white in origin or objective. In spite of this fact, each phase of the movement that sought to eliminate policies and practices that oppressed Black people was met with brutal force and state sponsored violence. At the same time, any activity that was calculated to resist the violent practices being exercised under color of law or privilege were soundly condemned as the illegal and unwarranted use of violence. America was very boldly standing for white supremacy and against the idea that Black people, wherever we were to exist, had no claim to equal rights.

The very concept that Black people anywhere on the face of the earth might claim the moral right to resist physical force with physical force was unconscionable. The roots of this warped thinking are very deeply rooted in the psyche of America. In fact, this sickness is so deeply rooted in the social framework of American justice until it flourishes undisguised to this date. The dictate prevails that Black people should be patient, appreciative, hopeful, and never fight back against authority. Any other standard, even today, is either criminal or at a minimum rebellious.

America’s Violent and Divisive Response to the Black Power Movement

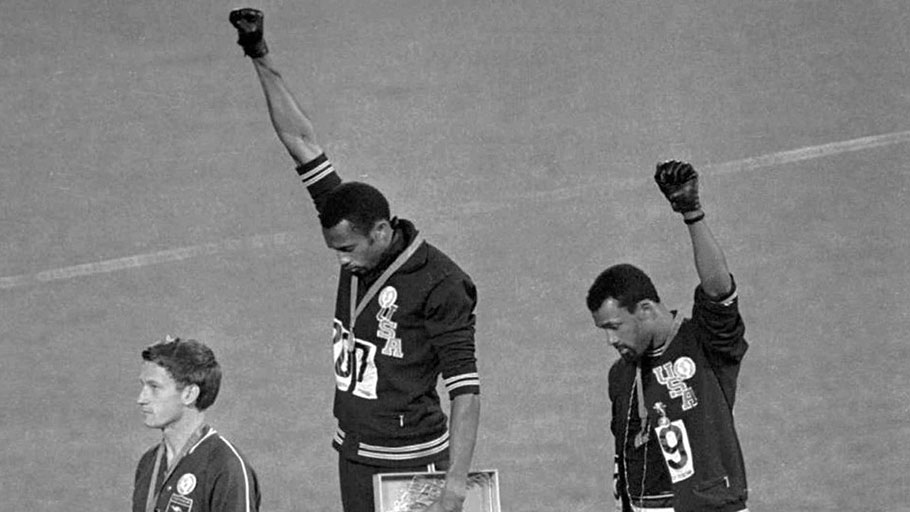

In spite of the dangers inherent in doing so, thousands of young Americans, to include African American first generation college aspirants, put their dreams and career plans on hold to stand in solidarity with unknown kin and fellow human beings who had been historically oppressed and marginalized. Their open commitment was to repair America, not to destroy it. Their strategies were “high minded” and conscious of the national and international impact that they would have on the world stage.

They framed America’s moral response with fire hoses, police dogs and vigilante killings that told the world and demonstrated to the world how “little” America thought that Black Lives mattered. The world was watching then and the world is watching now. This was happening in America, the Democratic bastion of the modern world, a century after the formal abolition of American chattel slavery. Interestingly, American citizens, who are still carrying the dossier for social justice and respect for the sanctity of black life, are still seen by the “state” as “irresponsible agitators”. The term “Slavery”, as it existed in different periods of American life, must never be used without descriptors of context or definition. To do so is to “normalize and de-fang” perhaps what was the most demonic system ever designed to rape an entire continent and systematically destroy a human population. I make this statement conditionally, out of the respect for the continuing suffering, abuse and devastation visited upon Native American Nations in the conquering of the North and South American continents.

The failure to incorporate an honest appraisal of American chattel slavery, and its lingering effects, into an analysis of the historic and contemporary challenge facing Black people the world over and to western civilization is to insure the inability to find a solution for repair. The Black Power Movement that evolved in this era literally scared the establishment. Fear, it could be argued, is the principal barrier that must be overcome in order to make advances in the struggle for social justice. Fear, is the standing enemy of Black Power. Fear of reprisal, fear of the loss of privilege, fear of the obligation to compete on equal terms.

Stokely Carmichael

These fears and others are all barriers to the creation of just and equitable societies. Long discussions were structured around the very simple and obvious meaning of the term “Black Power” that Brother Stokely Carmichael introduced into the conversation. The “establishment” never could manage to construct a logical, safe and comfortable translation of those two words. As often as not, community leaders of all colors and stripes seemed to be equally confused and offended by the term. The introduction of the term into the popular discourse of the Movement exacerbated tension and internal conflict. The Civil Rights Movement was maturing. The institutions of American society were neither prone to sleep or to accommodate that maturation. Due to the expansion of political consciousness in the society in general – particularly among the youth who were increasingly concerned with the Vietnam War – the “desegregation of lunch counters was rapidly creating a new movement energy and a broader focus on issues of international social and political justice. America had to respond and respond it did. It did so by using the successes of “the movement” to sow the seeds of division and adopt the time tested strategy of divide and conquer.

More importantly, and more directly, through the Counter Intelligence Program, it unleashed the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover. It allowed the FBI and American law enforcement to infiltrate, and to destroy by any means necessary – to include assassination – the opportunity for America to embrace the meaning of her creed. In brief, this plan destroyed coalitions, created suspicion, and generated new movement objectives. Government strategies segmented the civil and human rights struggle into a race for power, identity, and benefits among groups seeking Gay rights, Women’s rights, Indian rights, Black rights, Spanish rights etc. The negative but successful effects of this strategy were to be later reinforced through so called affirmative action programs and similar government sponsored activities. Black Power ultimately had to compete with “Green Power…$$$.” Green Power continues to be the great un-equalizer.

What Is The Next Step In The Movement?

What Black Leaders and Black Scholars need to study and understand is how to escape “the participation trap” and get back on “the empowerment track”. How did we wind up here? What are the factors and circumstances that resulted in the substitution of the word “Rights” for “Power” in our popular political vocabulary? How did a movement to secure “jobs and justice” turn in to a super-sized initiative “to integrate and foster brotherhood”?

More importantly, what accounts for Women’s Rights, Gay Rights, and white supremacy (however camouflaged) literally flourishing in this post movement era, while Black Rights and Indian Rights have yet to become a part of the modern “rights vocabulary” or thought process? Today, Black Americans have neither Black Power nor Black Inalienable Rights. This fact holds, in spite of the increased numbers of African American men and women who enjoy successful lives and careers. None of what can be responsibly identified as progress has served to sufficiently close the gap or to afford greater security and protection to Black life. The tea leaves are still relatively easy to read, if we dare to do so honestly. Social, political and economic inequality, continue to frame the lead paragraph in the message. Under-employment, under-education, mass incarceration and other forms of state complicit violence continue to provide the details for the rest of the story. The message now and for centuries has been recited without apology.

The question is whether or not we can accept the fact that the strategies for empowerment that we define and adopt cannot be constrained and defined by concerns that devalue collective Black self-interest. Neither can the conditions for Black political participation in the struggle to become self-determining, be subjected to the approval of the individuals and institutions who are also the architects of global Black oppression.

The Sankofa Moment

A “Sankofa moment” of reflection teaches that we must define new strategies and a new definition of Black progress. The trip to the top for a few has not been the blue print or the solution to provide the remedy for the masses. The evidence suggests that we must reconnect with the history of our past achievements and contributions to world civilization. The evidence further suggests that we must reconstruct the bonds of African solidarity that are so essential for global Black empowerment and for the elimination of global black marginalization. Finally, we must consciously seek to start a process to build a modern agenda for political, social, economic and educational Black empowerment. This foundational agenda must consistently be driven by the spirit of an earlier time when we proclaimed that we have “no permanent friends and no permanent enemies, only permanent interests”. The “scrubs” have been taken off and the report has been written. The conclusion accurately recites the fact that Black Power is dead. The cause of death is recited as abandonment and neglect. In spite of the death, what remains are a number of vital organs to be transplanted and a treasure trove of knowledge about how to better use and protect them in the next phase of the struggle. My prayer is that we will be wise enough, bold enough and free enough in our minds to do so.

Dr. William Small, Jr. is a retired educator, and a former Board Chairman and Trustee at South Carolina State University.