Activist Jason Jones celebrating with others after Trinidad and Tobago’s High Court ruled against the country’s anti-homosexual laws, outside the Hall of Justice, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, April 12, 2018. Photo by Andrea de Silva/Reuters

By Monique Roffey, NYR Daily —

On April 12, outside the Hall of Justice in downtown Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, the streets were alive with office workers going about their business, vendors hawking everything from CDs to shaved ice—the usual hubbub on a hot morning in the middle of the dry season. And yet, something unusual was taking place inside the Hall of Justice, and, as a result, over a hundred people had gathered on the steps outside, myself included. In 2017, a gay Trinbagonian man named Jason Jones had challenged the so-called “buggery law” of Trinidad and Tobago, the statute that had criminalized same-sex intimacy for more than four decades. After hearing from Jones’s counsel—the British lawyers Richard Drabble, a senior barrister, and Peter Laverack, a human rights specialist (Trinidadian lawyers Rishi Dass and Antonio Emmanuel had been crucial to the counsel’s initial consultations)—Trinidad and Tobago’s High Court ruled that these antiquated and explicitly anti-homosexual laws should be struck off the books once and for all, a historic win.

Section 13 of Trinidad and Tobago’s Sexual Offences Act, the “buggery law,” criminalized anal sex (both between two men and between men and women). In addition, section 16 of the act defined any gay sexual contact as “serious indecency.” These are colonial-era laws (revised over time) that still exist in many former British colonies. Jones and his team had struck at the heart of an arcane system of laws that were once put in place, without debate, to set standards of behavior under colonial control across the British Empire. But while England and Wales decriminalized consensual homosexual acts between two men twenty-one and older in 1967, many of Britain’s colonies, especially in the Caribbean, had already won their independence in the 1950s and early 1960s, with the sodomy laws still firmly in place.

Across the Caribbean two realities exist in conflict: the diversity and fluidity of beliefs and lifestyles having to do with sex and marriage within actual communities, and the staid and forbidding values touted by church leaders and politicians. Caribbean queer theorist Rosamond S. King—who just won Lambda Literary’s Lesbian Poetry Prize for her book Rock | Salt | Stone—explains in her 2014 investigation into sexuality in the Caribbean, Island Bodies: Transgressive Sexualities in the Caribbean Imagination, that while sexuality in the Caribbean is diverse—with multiple partnership relationships by both men and women, serial monogamy, informal polygamy, and same-gender and bisexual relationships—politicians and church leaders espouse conservative views to win votes. “If the realities of Caribbean sexualities are so flexible,” she writes, “then why do the region’s political leaders still act as though marital, heterosexual, monogamous nuclear families are—and should be—the norm? This behavior persists in part because the practice of espousing conservative (some would say Victorian, Brahmanic, Catholic, and Mohammedian) ideals allows political and religious leaders to promote a Caribbean cultural nationalism that is markedly different from the ‘loose’ morals perceived in the contemporary laws and popular culture of the global North.” In a chapter on homosexuality, King disputes the idea that the Caribbean is the most homophobic place on earth. She argues that homosexuality has always operated in the Caribbean region and does so under the structure of el secreto abierto, or “the open secret,” which not only permits but encourages acceptance of homosexuality in the region, as long as discretion is observed.

In their legal challenge, Jones and his team argued that section 13 and section 16 of Trinidad’s current law are unconstitutional and violate the rights to privacy, liberty, and freedom of sexual expression. Trinidad and Tobago’s constitution was written in 1976, when the country became a republic, severing the ties it had continued to maintain with Britain’s constitutional monarchy after the islands achieved independence in 1962. In 1986, its parliament amended the act, doubling the maximum penalty for sodomy between adults, and in 2000, increased the maximum penalty again to twenty-five years. But the amendment to the law also created an opening for Jones’s action, on the basis that the Sexual Offences Act nullified the “savings clause” written into the constitutions of former British colonies, which decreed that British laws could not be changed after independence. Since the Trinidadian government had amended the buggery law over the years, the law was open to reform. Because of this constitutional argument, Jones’s victory was not just a win for Trinidad and Tobago but has opened the way for similar legal challenges in the seven other Caribbean nations—and the thirty-six other countries in the Commonwealth—that similarly criminalize homosexuality. In fact, just yesterday it was announced that three Barbadians will be challenging their country’s own “buggery” laws, which, they argue, criminalize intimacy between consenting partners.

That April day outside the Hall of Justice was momentous. Over a hundred people held placards, signs, rainbow flags, all the usual paraphernalia of a Pride gathering. It wasn’t Port of Spain’s first open Pride event, but it was a rare public display for a community still fighting for wider acceptance. One woman held a large sign that read, “Nobody Knows I’m Gay.” Another’s said, “Closets are for Clothes.” There were well-known queer activists, as well as artists, journalists, filmmakers, and other supporters. There was also a strong showing from Trinidad’s conservative Muslim group, the Jamaat al Muslimeen, who came to protest against Jones.

Back in 1990, radical Muslimeen militants attempted a coup d’état in Trinidad, shooting and wounding the then-prime minister, A.N.R. Robinson, and holding parliament and the country hostage for six days while Port of Spain was laid to waste by looters. Yasin Abu Bakr was the mastermind of these events, and played an active part in capturing the national TV station, Trinidad and Tobago Television (TTT), in order to appear live to the nation in hourly broadcasts—until the army knocked him off the air. His role was to let the country know he’d replaced our prime minister. The coup ended, after six days of mayhem, only once the prime minister, with a gun to his head, had signed an amnesty agreement that allowed the gunmen to go free. At least twenty-four people lost their lives in the chaos, one of them a member of parliament, Leo Des Vignes. Shops and small businesses in downtown Port of Spain were burned to the ground—many people I know in Port of Spain know someone whose family business was destroyed. Bakr and his men were arrested on the spot, and awaited trial under lock and key for a short period of time. Unfortunately, Trinidad’s High Court upheld the amnesty, and when, four years later, the London-based Privy Council invalidated the agreement, Bakr and his men weren’t rearrested. Famously elusive, Bakr also refused to appear when called to testify at a 2010–2013 Commission of Enquiry into the coup.

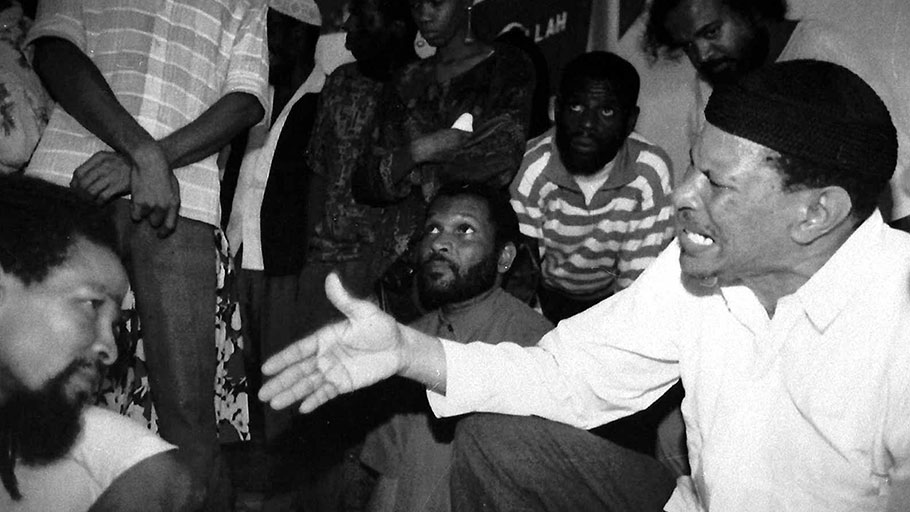

Yasin Abu Bakr with other members of the Jamaat al Muslimeen after his release in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, July 1, 1992. Photo by Willie Alleyne, AP Images

On this day, fifty or so members of Port of Spain’s Muslimeen arrived by bus and lined up, arms crossed, against the railings of Woodford Square, the famous scene of colonial independence protests in 1950s and, later, Black Power rallies in 1970. At one point, two women clad in jeans, black hijabs, and long gold earrings—striking figures among those waving rainbow flags—approached the steps of the Hall of Justice and proceeded to try to shout down and humiliate the most flamboyantly dressed—in some cases, barely dressed—among us. Soon after the women in hijabs retreated, I came face to face with Bakr.

In his seventies now, he is still a tall, vigorous, dapper figure. He was dressed in all white, his voice as rich and soft as butter. My 2014 novel House of Ashes examines the attempted coup, and I had spent much time speaking to those involved, but I had never managed to track down Bakr. And suddenly there he was, free as a bird. To encounter him there seemed an example of what Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier calls lo real maravilloso, a moment of authentic Caribbean magical realism. A man who had held the country at ransom, who had beaten and abused the prime minister, was there to decry the basic human rights and dignity of Trinidad and Tobago’s gay community. He was instantly mobbed by the local press. All I could do was stand and stare.

But this was not his moment. When the ruling was handed down, the crowd outside became jubilant. Inside the courtroom, Justice Devan Rampersad had spoken eloquently about human dignity, agreeing that the laws were indeed unconstitutional. Most people were tearful, including myself. Jason Jones’s legal challenge took courage—and it gave heart to the crowd. There was dancing, cheering. And then something strange happened: people started singing the national anthem, “Forged from the Love of Liberty.” We still sing the anthem at ceremonial events and functions in Trinidad and Tobago—but there, finally, the words side by side we stand seemed to truly express the island saying that “alluh we is one”—that we each might hope to find an equal place.

“It was a true postcolonial moment,” said my friend the well-known broadcaster Francesca Hawkins. “A day when human rights per se has been reset here in the region.” Colin Robinson, head of the Coalition Advocating for Inclusion of Sexual Orientation (CAISO), Trinidad’s grassroots LGBTQI organization, was among the first to emerge from the courtroom, giving a short speech that credited Jones’s bravery. I could see that Robinson was happy, smiling and shiny-eyed. When Jones appeared, my legs went weak—I was more than a little relieved. In late December 2015, he had been at a gathering at my flat in London when he quietly decided to forge ahead with the legal battle. That evening, we’d all read stories and poems to each other, as is my end-of-year tradition. I remember seeing Jason sitting on the floor, head in hands, deep in thought. He had come to the conclusion, that night, that this was a step that needed to be taken.

Outside the court, Jones spoke briefly to the press, saying, challengingly, that Prime Minister Keith Rowley should be proud of the progressive LGBTQI win, and he urged Rowley to stand with him when he attended the twenty-fifth annual Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting the following week in the UK, but Rowley remained silent on this issue. After leaving the Hall of Justice, I went for a beer with my friends Bonnie and Anna on Prince Street, where things seemed little altered. Reggae music boomed. The people of Port of Spain went about their business, as usual.

Many things have changed since the ruling. Perhaps the most significant outcome was British Prime Minister Theresa May’s strong public support of gay equality and human rights in the Caribbean and throughout the Commonwealth, and outright denunciation of the homophobic laws: “They were wrong then and they are wrong now.” Within days of the victory, however, the leader of Trinidad’s opposition party, Kamla Persad-Bissessar, called for a referendum to overturn the court ruling.

That proposal never got off the ground. But evangelical church leaders also damned the decision, as expected. Remarkably, though, the Catholic Archbishop of Port of Spain, Charles Jason Gordon, gave the ruling his public support. Days after the ruling, photos of Michelle-Lee Ahye, Trinidad’s track and field star and the gold medalist in the 100 meters at the 2018 Commonwealth Games, with her long-term girlfriend, Chelsea Renee, were leaked online and made front-page news in the Trinidadian press. This aggression backfired, as many of her countrymen and women rallied around her in support. Weeks later, Ahye married her girlfriend in the US. Another national hero, the calypso singer David Rudder, has also openly supported the ruling, an incredible shift in consciousness away from the music scene’s old cultural tropes of machismo and homophobia.

But the victory didn’t come without backlash. Trinidad and Tobago’s attorney general, Faris Al-Rawi, appealed the ruling immediately. Dozens of LGBTQI people in Trinidad and Tobago have lost their jobs, been thrown out of their homes by their parents or evicted by landlords, and targeted with death threats, cyber-bullying, harassment, and violence. The Caribbean Equality Project, a diaspora organization, has recently relaunched a solidarity campaign for an online fundraising benefit for Friends For Life, an LGBTQI group in Port of Spain who are currently coordinating temporary housing for those who’ve become homeless. On May 13, evangelical church groups came together, yet again, to march through Port of Spain and protest the ruling.

Jones, born and bred Trini to de bone, didn’t have much support from grassroots LGBTQI groups in Trinidad or in the UK. He crowd-funded his legal campaign, received grants, and lived on a shoestring for two years. A seasoned human rights activist, in the late 1980s Jones had participated in marches against section 28, a Thatcher-era British local government law that prohibited the “promotion of homosexuality” in schools, including “the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.” In the 1990s, he was on the board of the United Kingdom Lesbian and Gay Immigration group, which lobbied for, and won, the right of abode in Britain for the same-sex partner of a UK citizen. Back in Trinidad, he had also set up an LGBTQI advocacy group named I Am One, which is still in operation, now led by Zeleca Ztime Julien.

Groups in Trinidad had been caught, for years, in what they saw as a tactical straightjacket; act too fast and face a backlash, or even violence. Their plans for action had always been dominated by the need to keep community members safe. Jones, indeed, faced numerous death threats during his lonely campaign, demonstrating how hard, if not impossible, it would have been to live in Trinidad and Tobago during his challenge. Jones currently lives in the UK and flew to Port of Spain for the court appearances only. “Watching the backlash is heartbreaking and heart-lifting at the same time,” he said. “As someone who was made homeless myself by my own family, I totally empathize with those members of the community who suffered the same fate after my historic judgment.”

Despite that judgment, the work is not over. Attorney General Al-Rawi’s appeal will go all the way to the UK’s Privy Council, whose judicial committee acts as the highest appellate court for Commonwealth countries like Trinidad and Tobago. Jones and his team are confident the Privy Council will rule in favor of Justice Rampersad’s ruling. This, however, will take time—up to four years. Only then will the removal of sections 13 and 16 from the Sexual Offences Act, it is expected, be confirmed. In the meantime, Jones is adamant that his campaign is far from over. He recently told me: “The work ahead is to ensure that this landmark win doesn’t stagnate LGBT advocacy.… I am working now on putting into action a number of different projects to ensure that this historic achievement creates an unstoppable momentum that leads to further human rights being granted to our community.”

Six weeks after the ruling, what sticks in my mind are the words chanted that day by many of those outside the Hall of Justice: “Love is love.” The public appearance of Yasin Abu Bakr, Trinidad’s most notorious and once most dangerous man, was a grim specter of the past, but what it demonstrated was that, today, Port of Spain is not afraid of him, let alone interested in his opinions. The winds of change are blowing. I think of what Rosamond S. King calls the “open secret” of homosexuality in the Caribbean, and look forward to the day when Caribbean men and women can openly love whomever they want.