By Amy Ongiri, Los Angeles Review of Books —

Just out of sheer curiosity (I might regret this but): Why are people making comparisons between the Black Panther Party and the movie Black Panther? Like where did this expectation come from that because the movie is called Black Panther that it should in some way reflect the BPP? What am I missing?

Just out of sheer curiosity (I might regret this but): Why are people making comparisons between the Black Panther Party and the movie Black Panther? Like where did this expectation come from that because the movie is called Black Panther that it should in some way reflect the BPP? What am I missing?

— Alicia Garza, Facebook post, February 20, 2018

WHEN ALICIA GARZA raised the question of the relationship between Ryan Coogler’s 2018 film Black Panther and the legacy of the Black Panther Party, intellectuals, activists, and cultural influencers from across the political spectrum of black radicalism answered. Garza, as one of the founders of the Black Lives Matter movement, has a large stake in understanding the relationship of media culture to political culture.

One of the people who responded to Garza’s post, Crystal M. Hayes, is the child of a still-incarcerated member of the BPP, Robert Seth Hayes. Hayes lamented that while a meme showing her father and other still incarcerated members of the BPP superimposed over an image of the movie poster had 50,000 shares on Facebook, she was still having a hard time raising $10,000 for a legal defense fund. Others noted the ways in which cast members of the film perpetuated and flirted with the legacy of the Party, posing with imagery that invoked it on the covers of GQ and Rolling Stone. Influential journalist Davey D. Cook noted that given the movie’s prominent themes and its director’s hometown of Oakland, California, which was also the birthplace of the BPP, comparisons between the film and the organization were not only unavoidable but also completely necessary.

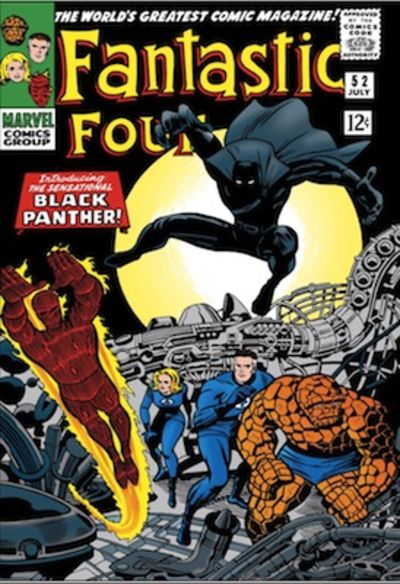

The character Black Panther first appeared in 1966 in Fantastic Four #52, and he became an Avenger two years later. He was the first black superhero in the Marvel universe, and the first African superhero as well. The Panther was among the first of the wave of black characters who began appearing in mainstream comics in the mid-1960s, in response to the changing climate brought about by the Civil Rights movement and its demand for the integration of African Americans into mainstream American culture.

In 1965, Dell Comics had published Lobo, the first US comic series to star an African-American hero. The series was cancelled after just two issues, as it proved too controversial for popular sale. But following the Panther, other black superheroes slowly took the stage. The Falcon, who appeared in Captain America#117 in 1969, was Marvel’s first African-American superhero. DC’s Teen Titansintroduced a recurring (although not initially superpowered) African-American character named Mal Duncan in 1970, and in 1971 the Panther’s co-creator Jack Kirby introduced DC’s first black superhero, the Black Racer, in Kirby’s series New Gods. 1972 saw the debuts of Marvel’s Luke Cage and John Stewart, an African-American member of DC’s Green Lantern Corps. In 1975, the Kenyan mutant Storm — the first black superheroine in mainstream comics — debuted in Giant-Size X-Men #1.

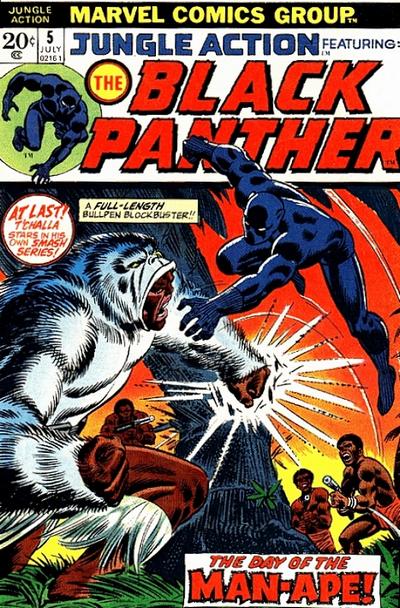

Though there were many different cultural, political, and social forces shaping the visual rhetoric of the black power movement during this period, the BPP, founded in Oakland in 1966, was one of the first groups to popularize the phrase “Black is Beautiful.” They did so in response to the paucity and stereotypical quality of black images reflected across all forms of popular culture in the United States, including comic books. In 1973, Marvel reacted to the changing climate brought about by the BPP and others by seeking to rebrand one of its comics, called Jungle Action, that now seemed too racist for changing times.

Jungle Action had originated at Marvel’s 1950s predecessor Atlas out of the tropes of the Tarzan movies and other popular jungle serials — tropes that were painfully outdated when Marvel decided to reprint the series in 1972. Jungle Action’s characters Lorna Queen of the Jungle, Tharn the Magnificent, and Jann of the Jungle are white adventurers whose stories play out against the backdrop of non-specific African jungles. The Africa that they occupy is peopled by a wide variety of exotic plants and animals, European and American mercenaries, and black characters who — even when they play central roles, such as Lorna’s mentor M’Tuba — are depicted as primitive stereotypes.

Jungle Action #5, the first to feature the Black Panther on the cover, included a story written by Don McGregor called “The Day of the Man-Ape.” As this title suggests, the issue had its own problems. Its cover features the problematic visual thematics that have historically tied people of African descent to savagery and troubling animal imagery, designating them as inhabiting an evolutionary stage in a human development closer to apes than to other men. The comic also plays on mythical associations of Africa with cannibalism, having the Man-Ape character bathe in the blood of a sacred white ape and eat its flesh in order to gain its strength.

Coogler’s film, of course, artfully renders the character as a symbol of black pride, eschewing the Man-Ape name and referring to him only as M’Baku, and even giving the actor Winston Duke a joke about cannibalism that he delivers to Martin Freeman’s CIA Agent Ross. M’Baku is, moreover, the only character to openly resist Agent Ross (who didn’t appear in the comics until 2000).

Coogler’s film, of course, artfully renders the character as a symbol of black pride, eschewing the Man-Ape name and referring to him only as M’Baku, and even giving the actor Winston Duke a joke about cannibalism that he delivers to Martin Freeman’s CIA Agent Ross. M’Baku is, moreover, the only character to openly resist Agent Ross (who didn’t appear in the comics until 2000).

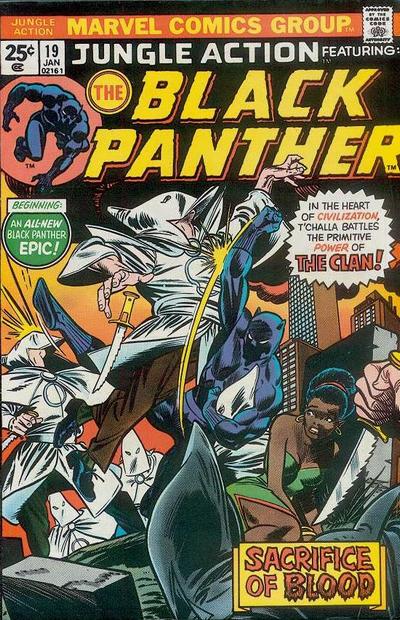

Yet under McGregor, and at the center of his own story line, Black Panther made great strides. By the end of McGregor’s run, he was in the United States taking on the “primitive” Ku Klux Klan. McGregor is generally credited as laying the groundwork for future black writers of the series, such as Christopher Priest, Reginald Hudlin, and Ta-Nehisi Coates.

But there are other ways to think about the relationship between the Black Panther and the Black Panthers than through the politics of black affirmation. Bobby Seale, who co-founded the BPP with Huey P. Newton, wrote about the inspiration for the Party’s name and symbol in a 1970 book entitled Seize the Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton. When he and his co-founders first conceived of the symbol, Seale claims, they were confronted by other African Americans at the poverty center where they worked who would ask them, “Why do you want to be a vicious animal like a panther?” Huey P. Newton would reportedly reply by explaining the complex simplicity of the panther iconography. “The nature of the panther is that he never attacks. But if anyone attacks him or backs him into a corner, the panther comes up to wipe that aggressor or that attacker out, absolutely, resolutely, wholly, thoroughly, and completely.” Seale laments the reaction of the group on hearing the explanation: “They didn’t want to understand that.”

But there are other ways to think about the relationship between the Black Panther and the Black Panthers than through the politics of black affirmation. Bobby Seale, who co-founded the BPP with Huey P. Newton, wrote about the inspiration for the Party’s name and symbol in a 1970 book entitled Seize the Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton. When he and his co-founders first conceived of the symbol, Seale claims, they were confronted by other African Americans at the poverty center where they worked who would ask them, “Why do you want to be a vicious animal like a panther?” Huey P. Newton would reportedly reply by explaining the complex simplicity of the panther iconography. “The nature of the panther is that he never attacks. But if anyone attacks him or backs him into a corner, the panther comes up to wipe that aggressor or that attacker out, absolutely, resolutely, wholly, thoroughly, and completely.” Seale laments the reaction of the group on hearing the explanation: “They didn’t want to understand that.”

With this emphasis on self-defense, it is perhaps no surprise that Newton and Seale borrowed their symbol from the nonviolent Civil Rights movement. The symbol was drawn, according to Seale, from the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. In 1965, this organization was attempting to register voters in a county that was 80 percent African American, but did not have one registered black voter. Organizer Stokely Carmichael realized that registering black voters had the potential to totally upend the power hierarchies of the United States. Because so many of the voters were deeply disenfranchised not only from voting but from education as well, the organizers chose a powerful visual symbol so that a potentially semi-literate population would know what they stood for.

But while the Civil Rights movement had nonviolence at its core, the politics of the Panthers was evolving to include the use of strategic, performative violence alongside the Civil Rights movement tactics of demonstrations, boycotts, and moral suasion. Though the BPP has come to be associated with a mythology of armed militancy, it was very intentionally named The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. As in Coogler’s Wakanda, that is, the Black Panthers’ original plan for arming themselves was not one of aggression or militarization, but rather one of proactive self-preservation.

McGregor’s multi-story narrative arc “Panther’s Rage” is said by many scholars to be one foundation for the contemporary graphic novel, and it is a key source for Coogler’s movie. “Panther’s Rage” provides a complex meditation on power, privilege, responsibility, and leadership, as Black Panther battles many rivals — including, in his first appearance, Killmonger — for control of Wakanda. Unlike the cartoonish villains common in other comics of the time, each of these foes harbors a somewhat legitimate claim to power in Wakanda. The Black Panther also brings his African-American girlfriend, Monica Lynne, to Wakanda, leading both her and the Wakandans to question whether she has any real place in the ruling hierarchy of the African kingdom. In one of the series’s most iconic stories, Jungle Action #11’s “Once You Slay the Dragon!,” Lynne advises Black Panther about the dangers posed to Wakanda by the encroachments of the outside world, warning him, “It’s more than a conflict of ideologies.”

Released in September 1974, at the tail end of the conflict in Vietnam, “Panther’s Rage” also explores the cost of warfare on both warriors and their communities. By this time the BPP had become a global movement, with organizations calling themselves “Black Panthers” as far away from Oakland as Polynesia and Palestine. It had also already helped to spawn an underground, proactively military organization called the Black Liberation Army. In a history that finds echoes in both the cinematic and comic book representation of the Black Panther, it was discord within the leadership of the party that led to the formation of the Black Liberation Army. In 1971, Minister for Information Eldridge Cleaver was expelled from the party over a conflict between himself and Huey P. Newton about the efficacy of armed struggle. Cleaver’s expulsion broke the party into sometimes-warring factions. BPP co-founder Newton was more much more wedded to the idea of armed self-defense and change on the local level than Cleaver, who saw armed struggle and internationalism as the way forward. There are echoes of this conflict in both “Panther’s Rage” and in the film’s representation of Erik Killmonger as a lost son of the African diaspora.

The history of the Black Liberation Army is still largely unknown and untold, in part because even now its membership still faces aggressive prosecution when they surface. Some of its most public members are able to be public because they have been incarcerated for decades, with no possibility of parole. And even while incarcerated, they face retribution. Russell “Maroon” Shoatz, one of the most vocal writers and intellectuals who participated in the movement, was held in solitary confinement for over 20 years of his sentence. Shoatz continues to write about the Black Panthers, the Black Liberation Army, and his thoughts on the possibility of Black liberation from prison. In his history “Black Fighting Formations: Their Strengths, Weaknesses and Potentials,” he quotes Carl von Clausewitz’s oft-repeated adage that “[w]ar is an extension of politics […] it is politics by different means” to critique the inability of black fighting formations in the 1960s and 1970s to build a sustainable aboveground political apparatus.

But perhaps Black Panther’s cinematic revival and massive success proves that the politics of revolution have never really gone out of style. “Panther’s Rage” writer Don McGregor, Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, and many others who worked on the original Black Panther comics series had served in the US military, with Kirby seeing actual fighting during World War II. They knew the cost of modern warfare, though not of the type experienced by the BPP or the Black Liberation Army. Perhaps that’s why they were able to imbue Black Panther’s adventures with such complexity of feeling in relationship to acts of war. By contrast, the movie’s fantasy of redemption beyond this cost, where all warriors shake hands and are at peace with each other, may ultimately be its most troubling legacy.

Mark Lofgren, a senior double major in History and Film Studies at Lawrence University, assisted with the research for this essay.

Amy Ongiri is associate professor and the Jill Beck Director of Film Studies at Lawrence University.