By Norimitsu Onishi and Selam Gebrekidan, The New York Times —

UMZIMKHULU, South Africa — Their fear faded as they raced back home, the bottle of Johnnie Walker getting lighter with each turn of the road. Soon, Sindiso Magaqa was clapping and bouncing behind the wheel of his beloved V8 Mercedes-Benz, pulling into familiar territory just before dark.

Minutes later, men closed in with assault rifles. Mr. Magaqa reached for the gun under his seat — too late. One of his passengers saw flashes of light, dozens of them, from the spray of bullets pockmarking the doors.

The ambush was exactly what Mr. Magaqa had feared. A few months before, a friend had been killed by gunmen in his front yard. Then, as another friend tried to open his front gate at night, a hit man crept out of the dark, shooting him dead. Next came Mr. Magaqa, 34. Struck half a dozen times, he hung on for weeks in a hospital before dying last year.

All of the assassination targets had one thing in common: They were members of the African National Congress who had spoken out against corruption in the party that defined their lives.

“If you understand the Cosa Nostra, you don’t only kill the person, but you also send a strong message,” said Thabiso Zulu, another A.N.C. whistle-blower who, fearing for his life, is now in hiding.

“We broke the rule of omertà,” he added, saying that the party of Nelson Mandela had become like the Mafia.

Political assassinations are rising sharply in South Africa, threatening the stability of hard-hit parts of the country and imperiling Mr. Mandela’s dream of a unified, democratic nation.

But unlike much of the political violence that upended the country in the 1990s, the recent killings are not being driven by vicious battles between rival political parties.

Quite the opposite: In most cases, A.N.C. officials are killing one another, hiring professional hit men to eliminate fellow party members in an all-or-nothing fight over money, turf and power, A.N.C. officials say.

The party once inspired generations of South Africans and captured the imagination of millions around the world — from impoverished corners of Africa to wealthy American campuses.

But corruption and divisions have flourished within the A.N.C. in recent years, stripping much of the party of its ideals. After nearly 25 years in power, party members have increasingly turned to fighting, not over competing visions for the nation, but over influential positions and the spoils that go with them.

The death toll is climbing quickly. About 90 politicians have been killed since the start of 2016, more than twice the annual rate in the 16 years before that, according to researchers at the University of Cape Town and the Global Initiative Against Transnational Crime.

The murders have swelled into such a national crisis that the police began releasing data on political killings for the first time this year, while the new president, Cyril Ramaphosa, has lamented that the assassinations are tarnishing Mr. Mandela’s dream.

But Mr. Ramaphosa is struggling to unite his fractious party before elections next year and has done little to stem the violence. His administration has even resisted official demands to provide police protection for two A.N.C. whistle-blowers in the case surrounding Mr. Magaqa’s murder, baffling some anticorruption officials.

The funeral for Sindiso Magaqa, the most prominent African National Congress politician assassinated so far, in Umzimkhulu last September. Credit – Thuli Dlamini/Sunday Times, via Getty Images

The recent assassinations cover a wide range of personal and political feuds. Some victims were A.N.C. officials who became targets after exposing or denouncing corruption within the party. Others fell in internal battles for lucrative posts. In rural areas — where the party has a near-total grip on the economy, jobs and government contracts — the conflict is particularly intense, with officials constantly looking over their shoulders.

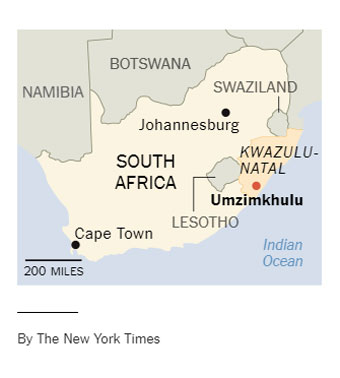

Mr. Magaqa’s province, KwaZulu-Natal, is the deadliest of all. Here, 80 A.N.C. officials were killed between 2011 and 2017, the party says. Even relatively low-level ward councilors have bodyguards, and many politicians carry guns themselves.

“It was better before we attained democracy, because we knew the enemy — that the enemy was the regime, the unjust regime,” said Mluleki Ndobe, the mayor of the district where Mr. Magaqa and five other A.N.C. politicians have been assassinated in the past year.

“Now, you don’t know who is the enemy,” he said.

More than any other, the death of Mr. Magaqa, the most prominent politician assassinated so far, has focused attention on the deadly scramble within the party that helped bring democracy to South Africa.

A rising star in the A.N.C. who had become a national figure, Mr. Magaqa returned to local politics in his hometown, Umzimkhulu. After accusing party officials of pocketing millions in the failed refurbishment of a historic building, Mr. Magaqa and two of his allies were killed in rapid succession.

Many others have suffered similar fates. This month in Pretoria, the capital, an A.N.C. councilor who had called for an inquiry into government housing was gunned down while driving her car with her three children. A few months earlier, a party official in a neighboring ward was shot dead near his home after exposing the shoddy quality of public housing.

In Mpumalanga, the province of Deputy President David Mabuza, an A.N.C. city council speaker was gunned down in front of his son outside his home after exposing corruption in the construction of a soccer stadium.

Here in KwaZulu-Natal, an A.N.C. councilor critical of corruption was shot to death last year while escorting a friend to her car. In March, an A.N.C. municipal manager known to be tough on corruption was gunned down behind a police station by two hit men. And this month, in a rare arrest, an A.N.C. councilor and the son of an A.N.C. deputy mayor were charged in the killing of an A.N.C. official who had led protests against corruption.

But few other political figures have been arrested in such killings, adding to a widening sense of lawlessness.

President Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa, center, waving to supporters at an A.N.C. event near Durban this month. Credit – Rajesh Jantilal/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

“The politicians have become like a political mafia,” said Mary de Haas, an expert on political killings who taught at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. “It is the very antithesis of democracy, because people fear to speak out.”

For good reason. After Mr. Magaqa’s death, Mr. Zulu, the whistle-blower now in hiding, loudly condemned corruption in Umzimkhulu. The impoverished municipal government spent a large chunk of its budget to refurbish a historic building called the Memorial Hall. But after five years and more than $2 million in public money, the project was a sinkhole of dubious spending, with little to show for it.

For breaking the code of silence, Mr. Zulu and another party official are now in grave danger, according to a 47-page report released in August by the Office of the Public Protector, a government authority that investigates corruption. The two whistle-blowers, the report said, fear that “they may be assassinated at any time.”

The Public Protector’s office urged the national police to provide security for the whistle-blowers and reprimanded Mr. Ramaphosa’s police minister for being “grossly negligent” in failing to do so. But the police minister rejected the report and moved to challenge it in court.

The Public Protector had a message for Mr. Ramaphosa as well: The president should “take urgent and appropriate steps” to protect the whistle-blowers. But Mr. Ramaphosa has not responded. Khusela Diko, his spokeswoman, said the president is consulting his police minister.

The government’s inaction reflects the A.N.C.’s inability — or unwillingness — to stop the internal warfare because it could expose the extent of corruption and criminality in its ranks, current and former party officials say.

“These allegiances go all the way to the top of the party,” said Makhosi Khoza, a prominent former A.N.C. politician who works at OUTA, an organization fighting graft. “That’s why the A.N.C. is not interested in this, no matter how many murders there are.”

For decades before the end of apartheid, different factions under the A.N.C.’s umbrella — communists, free marketeers, trade unionists, agents in exile — competed with one another, sometimes violently, as they fought white rule.

But the recent increase in killings inside the A.N.C. is a potent reminder of how far the party has strayed from creating, in the ashes of apartheid, a political order based on the rule of law.

The Public Protector’s investigation into the Memorial Hall has frozen the renovation. Umzimkhulu’s mayor, Mphuthumi Mpabanga, called the project a “dream” that would change “the lives of the people.”

But it has little resonance for many in Umzimkhulu, a vast municipality with pockets of extreme poverty. Margaret Phungula, 60, carries buckets to a muddy stream six times a day for water, adding spoonfuls of chlorine. Shown a photo of the Memorial Hall, she stared blankly.

“They’re not thinking of us,” she said of the town’s leaders. “We’re still suffering.”

From Idealism to Violence

The Memorial Hall in Umzimkhulu. After five years and more than $2 million in public money, there is little to show for the project. Credit – Joao Silva/The New York Times

In the arc of the A.N.C., Mr. Magaqa and his friends belong to the generation that includes Mr. Mandela’s grandchildren. Too young to have been politically active during white rule, they came of age in a new country — one forged by the party.

Their political lives, mirroring the A.N.C.’s post-apartheid trajectory, began with youthful idealism, followed by lost innocence and, ultimately, fratricidal violence.

Mr. Zulu, 36, the whistle-blower, always wanted to be an A.N.C. man. His grandmother took part in the A.N.C.-led potato boycott against apartheid in the 1950s, and he felt part of that legacy.

In his late teens, he fell in with a group of politically minded young men like himself. One of them stood out immediately: Mr. Magaqa, a skinny, stubborn teenager with a bright smile. The youngest in the group, he quickly became its leader.

Thabiso Zulu, left, an anticorruption activist and A.N.C. member, heard complaints from locals during a visit to KwaZulu-Natal Province. Credit – Joao Silva/The New York Times

Mr. Magaqa made a name for himself by leading a strike during high school. When students contributed money for a trip to Cape Town, the principal told them it had been put to other uses. Mr. Magaqa shut down the school for weeks.

The early 2000s were a hopeful time for the young men. Their elders in the A.N.C. had gained political freedom for black South Africans, so the young men turned their attention to breaking into an economy still dominated by the white minority.

Les Stuta — the second A.N.C. whistle-blower whose life is in danger, according to the Public Protector — was in the group as well. He recounted how they pledged to earn money to help their mothers, who worked as live-in maids for white families far away.

“Guys,” Mr. Stuta recalled saying often, “they must come back home.”

The young men traveled together across the vast stretches of the rural district to open youth league branches of the A.N.C., borrowing cars or hitchhiking.

Finally, in 2004, Mr. Stuta got a car — a beat-up white Ford Escort with a sputtering 1.3-liter engine. The young men stocked it with oil and water to deal with frequent breakdowns along the dirt and gravel roads to remote villages. When Mr. Stuta could not afford to replace the starter for six months, party meetings ended with the young men pushing the car back to life.

“That Ford Escort,” Mr. Stuta said, “was everything to us.”

Pattern of Kickbacks and Corruption

A.N.C. politicians, from left, Floyd Shivambu, Pule Mabe, Mr. Magaqa and Ronald Lamola in Johannesburg in 2011, when Mr. Magaqa held the No. 3 position in the party’s youth league. Credit – The Times, via Getty Images

By 2006, Mr. Magaqa and his circle got well-paid government jobs in Umzimkhulu. He got a car of his own, with a vanity plate: “Gogwana,” the grandmother who had raised him while his mother worked in Johannesburg.

When the A.N.C.’s youth league was established in Umzimkhulu, Mr. Magaqa became the chairman, beginning his rapid rise within the league — traditionally a springboard to leadership in the A.N.C. itself.

But something nagged Mr. Zulu. Within a few years, the overriding pursuit of positions and money consumed his peers. Suddenly, some were taking kickbacks, drinking rare whiskeys and prodding Mr. Zulu to drop his high-mindedness. Flipping Jesus’s teaching, they often asked him: Who can live on principle alone?

Soon, Mr. Zulu lost his government job and devoted himself to fighting corruption. But life was very different for his friend. At 27, Mr. Magaqa left the province for the national stage in Johannesburg. He became the A.N.C. youth league’s national secretary general, the No. 3 position, in 2011.

As soon as he was appointed, he went to a car dealership in a wealthy Johannesburg suburb where he bought an icon of South Africa’s moneyed class: a Mercedes-Benz sport utility vehicle, the ML 500 4Matic.

Mr. Magaqa raved about it to his friends back home — its V8 engine, the thunderous noise from the twin exhaust pipes.

“He felt like he’s got money,” recalled Phumlani Phumlomo, a childhood friend.

“He felt like he’s got money,” recalled Phumlani Phumlomo, a childhood friend.

How much money Mr. Magaqa made in Johannesburg — and how — were questions Mr. Zulu preferred not to ask.

“I don’t know how he acquired his money,” Mr. Zulu said. “Remember, he had access to everyone and anyone who’s big in the country.”

It only lasted a few months. Mr. Magaqa fell in one of the countless shake-ups within the A.N.C. and lost his position. He drove his Mercedes straight back to Umzimkhulu and put most of his money into a minor league soccer team, the Blue Birds. He recruited the best players, lodging them in a big house with cable and PlayStations. When his team won on the road — and it won a lot — he put up the players and coach in a hotel.

“But then his cash ran out,” said the coach, Mduduzi Ngubane.

With his money gone, Mr. Magaqa went back to what he knew best: politics.

A Hit List: ‘After Me, It’s You’

Relatives of Mr. Magaqa — including his mother, Khethiwe Dlamini, right — mourning his death, at his house in Ibisi. Credit – Joao Silva/The New York Times

In his political second act, Mr. Magaqa dove headlong into the issue that defined the A.N.C.: corruption.

Jacob Zuma, the party’s scandal-plagued leader, was president of the nation, and more than ever, local A.N.C. politicians began killing one another over positions, contracts and jobs.

In 2016, when Mr. Magaqa returned to politics, 31 politicians were assassinated, double the number from the year before, according to the tally by researchers. Of that total, 24 were killed in his province.

With the backing of regional A.N.C. power brokers, Mr. Magaqa became a councilor in Umzimkhulu and a member of its decision-making body, effectively becoming the leader of an insurgent A.N.C. faction.

The sudden return of a political star, someone who could still call on powerful figures in Johannesburg, was seen as an immediate threat to his party rivals in Umzimkhulu.

“He was too ambitious,” said the municipal manager, Zweliphansi Skhosana. “That was the problem that he had.”

Mr. Skhosana, a former high school teacher, knew Mr. Magaqa all too well. He had taught the young man from 10th grade through 12th grade. The two stood on opposing sides during the strike over money for the Cape Town trip.

Now they were facing off again. Regarded as the real power behind Umzimkhulu’s dominant A.N.C. faction, Mr. Skhosana still lived next to the old high school, in the area’s largest house, surrounded by a concrete wall and electrified barbed wire.

Right after joining the council, Mr. Magaqa zeroed in on the troubled renovation of the Memorial Hall. Little had been done to it, and the construction of a new annex was proving to be a disaster.

A few councilors had already raised concerns, calling it a classic public works boondoggle designed to siphon money into the pockets of politicians and their allies. Jabulile Msiya, a councilor whose ward included the hall, said she had been excluded from meetings on the project after asking too many questions.

Experts unconnected to Umzimkhulu’s politics, like Robert Brusse, an architect specializing in heritage buildings, agreed something was wrong.

A few weeks after being hired as a consultant for the project in 2016, Mr. Brusse went to see the Memorial Hall for himself.

“As I walked onto the site, I said, ‘There’s a rat here. This stinks,”’ he recalled.

The new building behind the Memorial Hall was “professionally incompetent” and a “complete waste of money for what is being produced,” he said.

Mr. Magaqa and his council allies demanded an independent audit — a motion quashed by the A.N.C.’s dominant faction in the municipality.

Mr. Skhosana, the municipal manager, dismissed any possibility of corruption. Mr. Magaqa, he said, was simply trying to stir up trouble to gain control over the local government.

Zweliphansi Skhosana, the municipal manager of Umzimkhulu, accused Mr. Magaqa of trying to stir up trouble to gain power. Credit – Joao Silva/The New York Times

He waved away accusations by councilors that the contractor had been chosen because of personal connections to a local official. The contractor simply had a “cash flow” problem, he said.

But the contractor, Loyiso Magqaza, contradicted him in a telephone interview, denying any cash flow issues. “They can never” blame me for the project’s failure, he said.

Mr. Magaqa, stuck in a deadlock with his former teacher, turned to someone his allies said he trusted fully: his old friend, Mr. Zulu.

Mr. Zulu had become a known corruption fighter in the province, gathering evidence and sharing it with officials he trusted. So Mr. Magaqa gave him what he described as official documents about the Memorial Hall.

The documents, which were reviewed by The New York Times, showed that after the contractor won the renovation contract in 2013, worth $1.2 million, the municipality paid the company and its subcontractor nearly two-thirds of the money, even though the project was far behind schedule.

Two years later, after the company and its subcontractor failed to finish, the municipality hired a different contractor for another $1 million.

In all, the documents do not unequivocally prove corruption on their own, but they show the municipality spent nearly all of the money it had budgeted for the hall — and ended up with little to show for it.

Mr. Zulu said he had grabbed the files and promised to pursue the case with his contacts in the police. But over the following months, Mr. Magaqa brandished the documents in the council and challenged leaders of the dominant A.N.C. faction, leading Mr. Zulu to wonder whether his old friend was also trying to use the issue to his personal political advantage.

The council speaker appeared to be moving over to Mr. Magaqa’s side, according to the speaker’s nephew, Mduduzi Thobela, an old friend who backed Mr. Magaqa during the high school strike. The speaker and Mr. Magaqa had been friendly, and were even related through marriage.

Then the killings started.

First came the warning: Three bullets pierced the storefront office where the council speaker worked.

A few weeks later, the speaker, Khaya Thobela, was sprinkling holy water in a religious rite in his front yard — and was gunned down where he stood.

A month later, the councilor expected to replace him, Mduduzi Shibase, was assassinated after opening the gate to his home. He had strongly supported Mr. Magaqa’s call for a forensic audit of the Memorial Hall.

Ms. Msiya, the councilor who had asked pointed questions about the project, got a worried call from Mr. Magaqa.

“‘Where are you? Don’t go out. I’m coming,’” she recalled him saying.

He showed her a “hit list” he got from a friend in a government intelligence agency, she said.

“‘It’s going to be me,’” Mr. Magaqa told her. “‘After me, it’s you.’”

‘We’re Not Safe’

Mr. Magaqa’s cousin Ntlantla Dlamini, right, with the politician’s bullet riddled car. Credit – Joao Silva/The New York Times

On July 13, 2017, a red BMW cased the neighborhood where Mr. Magaqa lived. His neighbors did not recognize the car. It had a license plate from Gauteng, the province where Johannesburg is.

Mr. Magaqa, accompanied by Ms. Msiya and other allies, had spent the day in a far corner of Umzimkhulu. But he was in a rush to head back home. The twin killings had shaken him, it was late afternoon, in the dead of South Africa’s winter, and the sun would be setting in no time.

“‘Let’s go, we’re not safe,”’ he said, recalled Nontsikelelo Mafa, a councilor and close ally.

As always, Mr. Magaqa drove his Mercedes himself and hid his gun under the driver’s seat. His bodyguard and another A.N.C. politician in the car also carried guns.

Talk of the killings soon gave way to more pleasant topics during the 45-mile drive. The car stereo played house music, blasting the Distruction Boyz’s “Omunye,” an instant hit about a party. The group was planning a party that evening, too, for Ms. Mafa’s 27th birthday.

By the time they got back, the music had Mr. Magaqa jumping in his seat. They pulled over at a hangout by the main road, where the red BMW had been waiting.

Mr. Magaqa spotted the hit men first.

“Don’t move,” he told the passengers in the back seat. Ms. Mafa saw two men with assault rifles approaching and Mr. Magaqa reaching for his gun.

Then, the flashes of light.

Sleeping in a Different Place Every Night

Mr. Dlamini, center, and friends, including members of a soccer team formed by Mr. Magaqa, visiting the politician’s grave in Ibisi. Credit – Joao Silva/The New York Times

Mr. Zulu’s cellphone rang minutes after the shooting. He reached out to senior police officials he trusted.

“The first one hour is decisive,” he said.

But the hit men weren’t caught, even though they drove a conspicuous car and had left witnesses: two women in the back seat survived with wounds to their legs.

Mr. Magaqa died about eight weeks later — from his injuries, the authorities said. His family insisted he had been recovering and was poisoned.

Of the nearly 40 politicians assassinated in South Africa last year, he was the most recognizable. The public broadcaster aired his funeral, five and a half hours long, live from a sports field. Hundreds came, including top A.N.C. politicians and a minister who flew in by helicopter.

The speeches were anodyne, or became rallying cries for the party. But Mr. Zulu had none of it. At a service beforehand, he said Mr. Magaqa had been killed for revealing corruption inside the party.

Today, fearing for his own life, Mr. Zulu sleeps in a different place every night. Two bodyguards, hired by his extended family, shadow him at all times. The three big men squeeze into his compact Volkswagen, which sinks a few inches every time they get in, as Mr. Zulu wages his one-man crusade against corruption.

“The A.N.C. is like an ocean that will cleanse itself,” he said, repeating it so often that he seemed to be trying to convince himself.

He, too, says he is fighting for what President Ramaphosa calls a “new dawn” for the nation. So why, he asked, has Mr. Ramaphosa remained silent on the Public Protector’s recommendations to provide him with security?

“I’ve been living like a hunted animal,” Mr. Zulu said.

In an empty, roofless room, wrapped in heavy blankets against the cold, Mr. Magaqa’s mother spoke about the promises A.N.C. officials made after her son died. His Mercedes sat in a corner of the backyard, riddled with bullets.

She was still waiting for the A.N.C. to solve the killing, to take care of her son’s four children, or even to fix his broken cars.

“Especially the Mercedes,” she said. “It’s destroyed our family, especially me. Each and every day, I see it, and everything comes back.”