A job fair in Washington DC in August. In April 2019, when the overall unemployment rate was 3.6%, the white unemployment rate was 3.1% while the black unemployment rate was 6.7%. Photograph: Andrew Harrer, Bloomberg via Getty Images.

Unemployment rate tells a different story about the economy when race is considered, even when job numbers are strong.

By Lauren Aratani, The Guardian —

What I’ve done for African Americans in two and a half years, no president has been able to do anything like it,” Donald Trump boasted in August, the latest in a series of statements in which he has claimed to be the best president for black Americans in history. Bahiyyah Dixon, 36, of Newark, New Jersey, isn’t feeling it. Even during a period of historic economic growth, the numbers are stacked most heavily against black Americans, like Dixon.

Back in April when the US unemployment rate fell to 3.6% – the lowest it has been since 1969 – Trump wasted no time celebrating. Dixon meanwhile was reeling from losing her job.

Dixon had been working at a commercial laundry service, making $9.50 an hour for washing, folding and packaging large loads of sheets for hotels in a factory outside Newark. At the factory, workers were starting to feel overworked. Many, including Dixon, were working overtime trying to make a wage they could live on, and employees were ordered to work quickly because of staffing shortages.

“They were trying to make us work faster and faster every day. We had overtime that was almost mandatory, just to meet our everyday needs,” Dixon said. “All of this was overwhelming, so we decided we needed help.”

Dixon and one of her co-workers decided they should try to unionize. They connected with the Laundry Distribution and Food Service Union (LDFS), a local chapter of the Service Employees International Union, and started to collect addresses from their co-workers to start the process of organizing.

When Dixon’s employer learned that she was trying to unionize her fellow employees, she was fired. It took months for Dixon to find another job. In the meantime, she ate into her savings to support herself and her 13-year-old son during her job hunt, stalling her dream of owning a house.

“I’m just looking for my family to be comfortable, able to live. My son has an education because I do want him to go on to college, I do want to be able to pay for my child’s education,” said Dixon. “I’m not looking to be rich, I’m just looking to be comfortable.”

When race is considered, the unemployment rate tells a different story about the economy, even when job numbers are strong. Historically, the black unemployment has always been almost double that of the white unemployment rate. For example, in April 2019, when the overall unemployment rate was 3.6% – the lowest it has been in 40 years, the white unemployment unemployment rate was 3.1%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The black unemployment rate was 6.7%.

Even as the black unemployment rate hit a record low of 5.5% in August it was still over 2% higher than the white unemployment rate.

The disparity has existed since the unemployment rate was first disaggregated by race in 1972. A report from the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) published in March said there “has historically been a wide gap in unemployment rates between black and white prime-age adults” led primarily by disproportionate unemployment between black and white males.

Back in April when the US unemployment rate fell to 3.6% – the lowest it has been since 1969 – Trump wasted no time celebrating. Photograph: Bill O’Leary, The Washington Post, Getty Images.

The CEA said that its review of research points to differences in education levels, discrimination in the labor market, the “first fired, last hired” effect – which is the widely documented phenomenon that black Americans are the first to experience the effects of the recessions and take the longest to recover – and the effects of mass incarceration as the main factors between the employment disparities.

By this point, experts say the inequality has become the unspoken double standard in the American economy.

“If we were still with a national [unemployment] rate of 6%, we wouldn’t think it’s that great,” said Valerie Wilson, director of the Race, Ethnicity and the Economy program at the Economic Policy Institution in Washington DC.

“We’ve sort of normalized this inequality and we expect the black unemployment rate to be double the white rate, so in that context, it’s easier for people to think that [the overall rate] is a great thing.”

The higher-than-average black unemployment rate is just one of many data points that show a booming economy does not mean equality for black Americans. There is a serious wealth gap between white families and black families. The median white family has 12 times the amount of wealth than the median black family. Income disparity exists across all education and income levels. A study published in 2018 that used an unprecedented amount of data – 20m records from Americans – showed that black men who were born into low-income families were more likely to end up low-income themselves than any other gender or race.

Much of the wealth gap can be attributed to disparities in home ownership. About 43% of black families own a home, compared with 72% of white families. Black homeownership has actually decreased since 1987, while white, Asian and Hispanic homeownership all increased during the same time period, according to a 2018 report from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies.

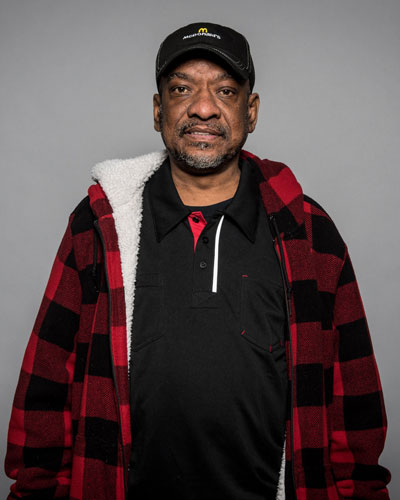

George Thomas, who works at a McDonald’s in Chicago for $13 an hour, has taken on a second job to subsidize his bus fare to get to his McDonald’s job. Photograph: Courtesy Christopher Dilts, SEIU.

There is also a stubborn wage gap between black and white Americans. In 2016, black Americans made 82 cents to every dollar that a white American made. The disparity is even worse for black women who make just over 60% of white men’s earnings and 89% of black men’s earnings.

“Inequality is costly on the people who are burdened by it,” said Andre Perry, a fellow at the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution.

“When you’re not making the kind of commensurate income, you’re living farther away, you have more commute time, you have less discretionary time, you’re spending more money on various transactions that you wouldn’t have to spend.”

George Thomas, 52, of Chicago works at a McDonald’s for $13 an hour. He is usually scheduled to work shifts that run from 6am to 2pm, but the store often sends workers home if it is not getting foot traffic. With unstable hours, Thomas has taken up a second job working as a washroom attendant at a restaurant in downtown Chicago, mostly to subsidize his bus fare to get to his job at McDonald’s.

“I love to work – I work seven days a week, but I have no ‘off’ days, and it still isn’t good enough,” Thomas said. “I don’t have a car, but I do have a place to live. So I either have to get a car and live in the car or get an apartment, and I can have access to a restroom and all of that.”

For the last four years, Thomas has been a part of Chicago’s Fight for $15 movement, pushing Illinois to adopt a $15 minimum wage. In February, the state passed a law that would gradually increase the minimum wage by 2025 – a victory for the local movement – making it one of five states that promise to implement a $15 minimum wage in coming years.

Along with increasing the minimum wage, experts say that diversity initiatives that prevent and address racial discrimination in hiring, targeted job training, stronger unions and general policies that can help black Americans built their wealth and assets will be necessary to eliminate the persistent economic racial gaps.

But the first step to progress may just be changing the way we talk about the economy.

“If you don’t ever look at an economy … by race, then you’re really not trying to get a full picture of the economy,” said Perry, of the Brookings Institution.

“We have to figure out ways to close disparities, but you can never do that if you are constantly saying how great the economy is.”