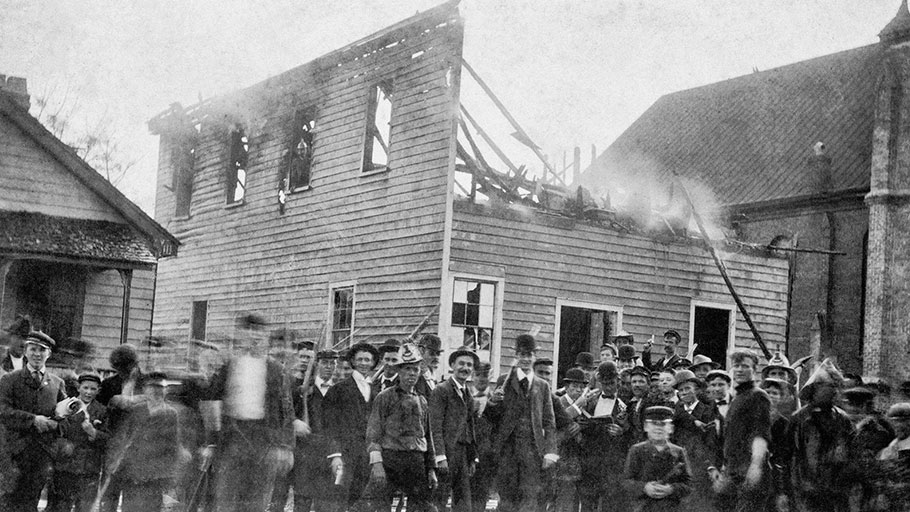

A mob of white men posing in front of the office of the black-owned Daily Record newspaper after burning it down, Wilmington, North Carolina, November 10, 1898. (Alamy)

Uncovering the truth about the 1898 massacre of black voters in Wilmington, North Carolina.

Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy by David Zucchino. Atlantic Monthly, 426 pp., $28.00; $17.99 (paper; to be published in January 2021)

Political violence, especially around elections, has a long history in the United States. In the antebellum era, white nativist Protestants often rioted against Catholic immigrants because of the perceived threat of Irish voters and their “popery.” In the New York City draft riots of 1863, white mobs murdered African-Americans over conscription into the Union Army. During Reconstruction, political terror and murder became an almost normal part of southern politics. In 1871 white mobs in Meridian, Mississippi, killed approximately thirty blacks in political violence that first broke out during a court trial. In 1873 in Colfax, Louisiana, as many as 150 African-Americans were killed, many execution-style, as white mobs rejected the results of a gubernatorial election.

But the coup in Wilmington, North Carolina, in November 1898 may deserve first place in this nineteenth-century gallery of horrors. That month there was a concerted, carefully planned, and successful effort to violently suppress the black vote, eliminate black elected officials, and restore white control of the city of Wilmington, as well as the entire state, to the Democrats for the cause of white supremacy. Leaders of the coup employed tactics ranging from vicious newspaper propaganda and economic intimidation to arson and lynching. Dozens of African-Americans were killed and black political life in the area was snuffed out in a matter of days: 126,000 black men were on the voter rolls of North Carolina in 1896; by 1902, only 6,100 remained.

What happened in Wilmington has long been a highly debated problem in historical memory, with the facts obscured for generations by the coup’s perpetrators and their apologists. David Zucchino’s engaging and disturbing book, Wilmington’s Lie, not only vividly reconstructs the events of 1898 but reveals the mountain of lies that has stood in the way of a truer, if not a reconciled, history. All those in America who do not understand the old and festering foundation of contemporary voter suppression should read this book. The Democrats of 1898 in North Carolina had the same aims, and some of the same methods, as today’s Republican vote suppressors, scheming and spending millions of dollars to thwart the right to vote with specious claims about “voter fraud.”

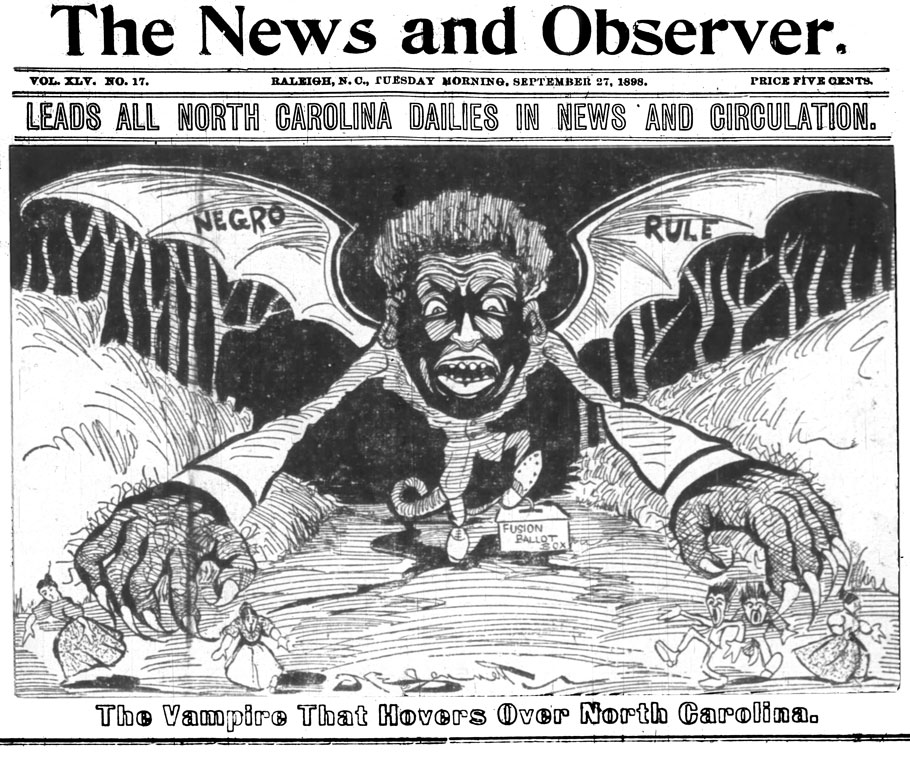

September 27, 1898

Wilmington’s bleak story of voter suppression stems from a tale of two Reconstructions. One involved the experience of defeated white Confederates and their sons and daughters; the other rested in the achievement of civil and political rights for emancipated black North Carolinians. By 1865 360,000 slaves had been liberated in North Carolina. But as Zucchino notes, “any civil liberties envisioned by the Emancipation Proclamation had not materialized by the summer and fall,” and soon Wilmington’s former mayor, “an ardent white supremacist,” was back in his post, with a police force led by a Confederate general and composed mainly of Confederate veterans. An emissary from President Andrew Johnson reported, “Wherever I go—the street, the shop, the house, the hotel, or the steamboat—I hear the people talk in such a way as to indicate that they are yet unable to conceive of the Negro as possessing any rights at all.”

In the decades following the Civil War, white Democrats, the oldest of whom still remembered the Nat Turner slave insurrection of 1831 in southeast Virginia, preferred to fixate on the short period between 1866 and 1868 when they were in power, after the state legislature passed a Black Code that, Zucchino says, “restored blacks to near-slave status” and refused, by a vote of 138–11, to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship to former slaves born in the US and guaranteed equal protection under the law. Blacks and their Republican allies preferred to remember the five thousand black men from North Carolina who formed the African Brigade in the Union Army during the war, as well as the state’s constitutional convention in 1868, gathered under the authority of the Reconstruction Acts, when among the 120 delegates, 107 were Republicans, thirteen of them black. With nearly 80,000 black men registered to vote in the state (compared to 117,000 white men), the radical constitution, enshrining black suffrage, won approval that year by a vote of 93,086 to 74,086 statewide, despite a vigorous campaign of intimidation by the Ku Klux Klan.

From that day forward, for the white supremacists of North Carolina, black voters became a contagion to be wiped out. The Democrats won back the state legislature in 1870, and within six years regained the governorship too, “congratulat[ing] themselves,” Zucchino writes, “on redeeming the state in the name of white supremacy.” They undermined the black vote by, among other things, eliminating the popular election of county commissioners and using procedural ruses to disqualify black voters. As Zucchino puts it:

Well before the close of Reconstruction in 1877, the vengeance of the Redeemers had essentially suspended the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments in North Carolina. White supremacy was triumphant. For the next seventeen years, the Redeemers ruled North Carolina.

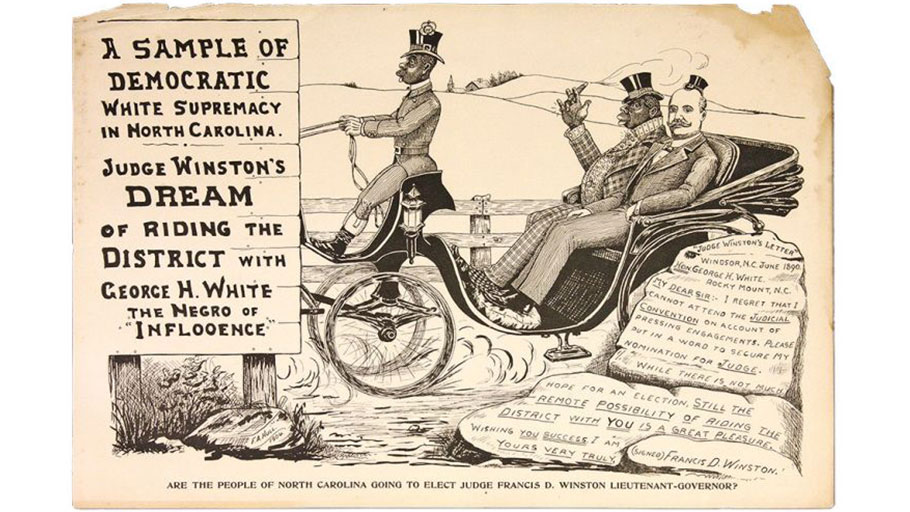

Yet North Carolina was an exception in many ways among former Confederate states. Even with the Redeemers in charge, the lights never went out on its black political life in the 1880s. The freedpeople had white allies in the Republican Party, as well as in the Fusionist movement of the early 1890s, in which some Populist whites joined with Republican blacks in imagining a “New South” of shared economic progress. By 1894 an interracial coalition of Republicans and Populists controlled the state legislature, and the second congressional district (including Wilmington) had elected a black man, George H. White, as its representative. The “Black Second” was a source of pride to Carolina African-Americans, as were the three black aldermen on Wilmington’s ten-person city council, the city’s ten black policemen (out of twenty-six), and its black coroner and health inspectors.

A family of African Americans photographed in Wilmington, 1898

Zucchino’s writing is crisp and declarative. Some of the book reads like in-depth reporting, yet he also expresses a careful level of moral indignation against the blunt racism he uncovers. His portraits of the three principal leaders of the white supremacy campaign in 1898 are particularly skillful. They were Josephus Daniels, a viciously racist and talented propagandist who owned and edited the Raleigh News & Observer; Furnifold Simmons, the chair of the state Democratic Party and the organizational mastermind of the coup’s operations; and Alfred Moore Waddell, a former Confederate officer, congressman, and popular orator. The three of them together were exceptional opportunists with fierce political ambitions. With the help of thousands of “Red Shirts”—bands of heavily armed men adept at intimidation and ready to kill—they sought the liquidation of black men from political life and the overthrow of the state of North Carolina. With arsenals of guns, big and small, the campaign declared its aims overtly; as a Simmons deputy put it with precision, “We must either outcheat, outcount or outshoot them!” They accomplished all three ambitions.

Daniels and Simmons were what the historian Joel Williamson once called the “children of Reconstruction,” haunted by memories of the loss experienced by their parents during the Civil War. They, and thousands like them, practiced a radical racism that demanded vengeance against “the menace of the freed slave”—first through the humiliation of black people and then through their political eradication. They believed in fixed racial traits and spread the idea that black Americans had somehow degenerated into dangerous behavior since liberation from slavery, manifested in aggression, especially sexual assaults on white women. These lethal concoctions of race and sex in the minds of radical racists formed a “psychic core,” wrote Williamson, of a new, violent redemption.

While Simmons built alliances and Daniels kept up a drumbeat of virulently racist cartoons and editorials full of misinformation throughout the run-up to the election of November 8, 1898, Waddell was the rhetorician of this movement. A generation older than Daniels and Simmons, he was called “colonel” though he had never attained the rank, came from white planter-class aristocracy, and mouthed their grievances. He found white supremacy his path back into politics. He voiced a ferocious brand of paternalistic racism. At huge rallies Waddell transformed Simmons’s two-hundred-page handbook of white supremacy methods and electoral strategies into rousing oratory that had working-class white men on their feet with their Winchester rifles held high.

The black man, preached Waddell to an audience of nearly a thousand people in Wilmington on October 24,

has never, during all these 30 centuries, exhibited any capacity for self-government…. Whenever he has been civilized by white men and then left to himself, he has invariably reverted to a condition of savagery…. If a race conflict occurs in North Carolina, the very first men that ought to be held to account are the white leaders of the Negroes!

At another rally before eight thousand people on November 7, Waddell called them to arms: “Go to the polls tomorrow,” he shouted, “and if you find the negro out voting, tell him to leave the polls. And if he refuses, kill him! Shoot him down in his tracks!” The campaign ran training sessions on how to stuff ballot boxes and met with employers to make sure white men had the day off to vote.

The bloodlust for the Wilmington white supremacy campaign came, says Zucchino, from the “core white conviction that any sex act between a black man and a white woman could only be rape.” This old but pervasive canard drove political organization and white frenzy more than some readers may grasp. There was also the threat that, as Zucchino puts it, “a black man who could vote or hold public office was a man who might…become a rival for the affections of white women.”

F.A. Hull, 1904. The “Negro of ‘Inflooence'”

The population of Wilmington all lived within the bitter restrictions of segregation. The Wilmington city school district spent $858 a year per school for whites and $523 per black school. Most black children attended school only through sixth grade, whites through twelfth. Modern technology had arrived in Wilmington, but the first telephones and electric trolleys were not shared between black and white neighborhoods. De facto Jim Crow quietly sauntered into town before his de jure big brothers loudly took over.

One person in the middle of the drama was the young journalist Alexander Lightfoot Manly. Born in 1866, he was the grandson of an antebellum North Carolina governor, Charles Manly, and one of his enslaved women, Lydia; though he could pass for white, he refused to. Manly grew up in a stable working-class environment, worked as a housepainter, attended the Hampton Institute in Virginia, and by the early 1890s brought his political passion to a newspaper, the Record, in Wilmington, which he built with his brothers into what he claimed was the only black daily in the world.

As early as 1895 Manly audaciously reminded white Carolinians that black voters outnumbered them in Wilmington. In August 1897 he wrote a column about race, sex, and lynching after a group of black Baptist ministers near Raleigh published a statement that condemned lynching but also, according to Zucchino, “accepted the entrenched white supremacist principle that no sexual union between a black man and a white woman could possibly be consensual.” Manly attacked them without reserve, reminding the clergy that white men had for generations raped black women without consequences, and arguing that laws punishing rape should apply equally to blacks and whites.

In the summer of 1898, with Daniels raving in Raleigh about an “incubus” of black rapists that “must be removed,” the pro-lynching activist Rebecca Latimer Felton, the wife of a Georgia congressman, weighed in with a widely publicized speech about “poor white girls on…secluded farms” preyed upon by black farmhand rapists. “If it needs lynching,” shouted Felton, “then I say lynch; a thousand times a week if necessary.” North Carolina newspapers reprinted the speech in August, and Manly struck back with an editorial that would be his undoing.

“Every Negro lynched is called a ‘big, burly, black brute,’” he declared in the Record,

when in fact many of those who have thus been dealt with had white men for their fathers, and were not only “black” and “burly” but were sufficiently attractive for white girls of culture and refinement to fall in love with them as is very well known to all.

He denounced Felton and all her accomplices as “a lot of carping hypocrites” and did not pull a single punch. “Don’t think ever that your women will remain pure,” he concluded, “while you are debauching ours. You sow the seed—the harvest will come in due time.”

“The whites of Wilmington had never read anything like it,” Zucchino writes. “A black man had mocked the myths that had sustained whites for generations, piercing the buried insecurities of Southern white men.” By challenging Felton in print, Manly endangered his life and livelihood as well as the marriage and family he had anticipated. He had courted and become engaged to Carrie Sadgwar, the daughter of a black man he had worked for as a painter. Manly had achieved status in the community as a Sunday school teacher and deputy registrar of deeds. In this dangerous racial environment, he laid everything on the line to expose the South’s oldest taboo.

When it came to race and sex in the South, speech was not free. When Furnifold Simmons read Manly’s editorial, Zucchino writes, “he believed Manly had handed whites a perfectly valid pretext to lynch him and torch his newspaper.” But Simmons and his team of plotters resisted screams for Manly’s immediate lynching:

Simmons recognized the value of timing white outrage for maximum political impact. August was too early. Simmons advised the city’s white elite—planters, politicians, lawyers, and merchants—to suppress the explosion of white rage until closer to Election Day.

In his Record Manly tried to stand firm while some blacks begged him to apologize. The days surrounding the election took place, writes Zucchino, as a kind of “carnival” of terror and racist catharsis. Simmons’s patience paid off when well-planned violence broke out on the day of the coup, two days after the election itself.

Black men in Wilmington risked their lives to vote on November 8; only about half of those registered actually cast their ballots. Democrats stuffed ballot boxes in gerrymandered black precincts and destroyed Republican ballots while white men, as Zucchino puts it, “accosted blacks at gunpoint in some wards, forcing them to turn back as they tried to reach polling stations.” In white neighborhoods, rumors spread of black violence—rumors that Zucchino states were “pure fiction”: “Virtually all the armed men who remained on the streets throughout the night were white, not black.”

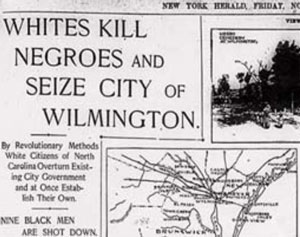

Newspaper headlines the following day announced the Democrats’ victory: “Our State Redeemed—Negroism Defunct,” said the Wilmington Messenger; “White Supremacy Receives a Vote of Confidence,” wrote the Raleigh News & Observer. Nearly a thousand white men gathered that morning inside the courthouse “to set in motion,” Zucchino writes, “the long-standing plan to overthrow the city government…and ensure that black men never again held office in Wilmington.” Zucchino quotes a Washington Post correspondent marveling at the “candor” of the leaders, who acted with the “stateliness of a Greek tragedy.” With Red Shirts ready to thwart a supposed “black insurgency” that never occurred, Waddell called in a jerry-rigged committee of black men to accept seven Orwellian “resolutions” of surrender. The preamble to this document carried the grandiose title “Wilmington Declaration of Independence.” One resolution boldly announced that blacks would be treated “with justice and consideration” as long as they obeyed “the intelligent and progressive portion of the community.”

On the morning of November 10, a mob of more than five hundred white men, led by Waddell, gathered at the armory. Zucchino allows the words of these American terrorists to tell the truths they and their successors would suppress for decades. Shouting “Victory! White Men!” as though trying to convince themselves, the mob, which had grown to over a thousand people, went in search of Manly to stage a spectacle lynching; denied satisfaction because Manly had slipped town, they burned the building that had housed his newspaper and stood for a group photograph. Soon men from the mob began to fire their guns throughout the neighborhood.

Estimates vary as to how many people were murdered. There may have been up to sixty bodies, found all across town, many shot in the back, some humiliated first on their knees, some dying near or fleeing from their homes. Droves of black families fled into nearby swamps, cemeteries, and pine forests. After coup leaders forced resignations from the mayor, police chief, and board of aldermen, Waddell was declared the new mayor. The Democratic city clerk dutifully kept the “minutes” of the coup itself, a banality of evil conducted without the slightest sense of irony.

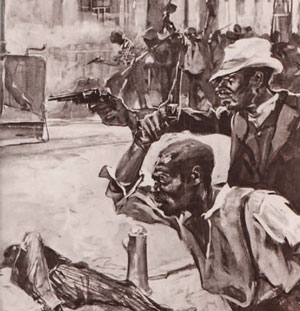

Black resistance to the racist massacre was strong… but not enough to fight off the larger racist mob.

Zucchino is at his best as he builds the historical infrastructure of lies from which the story of Wilmington emerged. These kinds of lies, as we have learned in our own historical moment, are the particular stock-in-trade of demagogues who believe their power is unchecked, or who dissemble them before and after their acts of suppression. Waddell and Daniels rushed to declare their handiwork “strictly in accordance with law,” claiming that blacks were the ones who most benefited from the white supremacists’ takeover. A hastily conducted coroner’s jury concluded that no one could be prosecuted for the killings of November 10 because “the said deceased came to their deaths by gunshot wounds inflicted by some person or persons to this jury unknown.” The truth was whatever the coup leaders said it was.

Amid parades and bands playing “Dixie,” a narrative of victory poured forth from press and pulpit. A Reverend James Kramer delivered a sermon on the Sunday after the coup in which he held that “God from the beginning of time intended that intelligent white men should lead the people and rule the country.” In the violence, Kramer contended, “the negro was the aggressor. I believe that the whites were doing God’s services.” Another minister, Reverend Peyton Hoge, who had himself carried a rifle during the violence, said Wilmington had been, like Jerusalem, “redeemed for civilization, redeemed for law and order, redeemed for decency and respectability.”

After the 1898 massacres the Democratic Party swiftly took over the entire state of North Carolina. Simmons went on to a long career in the US Senate, while Daniels rose to national stature eventually in President Woodrow Wilson’s cabinet, along with other staunch segregationists. A wave of disfranchisement and other Jim Crow laws flowed from the state legislature. Manly left the state, part of a black exodus from North Carolina.

The successful destruction of Wilmington’s black community and the political decapitation of its leadership is the essential tragedy of the coup. John Dancy, the county registrar of deeds and a conservative follower of Booker T. Washington, tried against the odds to accommodate to the white supremacist threat, futilely counseling patience and good order. William Henderson, fair-skinned and mostly Cherokee, was an intrepid lawyer who had fled to Wilmington’s more welcoming environment in the mid-1890s after being run out of Salisbury, North Carolina, for defending a black man accused of murdering a white man. He made his name as a Republican Party organizer, then, with his family under dire threat, fled the state after the coup. George H. White, the sole black member of Congress, fled too, and hoped for federal intervention in the aftermath of the Wilmington murders as he also fought (unsuccessfully) against the wave of Jim Crow laws that followed.

In Washington, D.C., only months after the massacres, Manly came out of hiding to lobby President William McKinley (a Republican) for federal intervention in Wilmington. But McKinley kept utterly silent about the coup, in obedience to states’ rights; a cursory Justice Department investigation went nowhere. Charles Aycock proudly announced in 1900, the year he was elected governor of North Carolina, that Democrats had “taught them [i.e., whites and blacks alike] much in the past two years in the University of White Supremacy.” More than six decades passed before North Carolina began to officially unlearn that education.

From the opening sentence—“The killers came by street car”—to the concluding lines about how irreconcilably this story looms in American history, Zucchino’s work is both enlightening and painful. At times the reader feels some whiplash from being pushed back and forth through history. His explanation of the election of 1876 as an end of Reconstruction is a bit simplistic. The story of the political success of blacks in North Carolina by the 1890s needs some comparison to the Readjuster movement in Virginia in the 1880s, which for a few years promised, though failed to attain, interracial politics. But Zucchino is a marvelous writer. Only at the end of the book does he draw any direct comparison to today’s voter suppression in North Carolina and elsewhere, but one feels that treacherous legacy on nearly every page.

Jane Cronly, a white woman who kept a diary during the coup, was horrified by what she witnessed. Her viewing of several killings prompted this recollection:

The whole thing was with the object of striking terror to the man’s heart, so that he would never vote again. For this was the object of the whole persecution; to make Nov. 10th a day to be remembered by the whole race for all time.

Newspaper clip

The Wilmington events have gone by several names: “riot,” “coup,” “massacre,” or, over the decades by its defenders, “victory.” By any measure they might also be called a pogrom. Last year, in an essay about the pogrom against the Jewish population of Kishinev in 1903, the philosopher Avishai Margalit argued that some instances of mass violence become symbolic because they have received lasting representation in art—for example, Guernica, Picasso’s 1937 painting protesting the fascists’ bombing of civilians in Spain; The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, Franz Werfel’s 1933 novel about the Turkish genocide against the Armenians; or “Babi Yar,” Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s poem about the massacre in Kiev in 1941.

To that list Americans might add poems, songs, and novels about lynching.

The Wilmington coup inspired at least two novels by black writers in its immediate aftermath: Charles Chesnutt’s The Marrow of Tradition (1901) and David Bryant Fulton’s Hanover; or Persecution of the Lowly, Story of the Wilmington Massacre (1900).

But it took a 1951 doctoral dissertation by Helen Edmonds, a 1984 book by H. Leon Prather, and extensive public history activism to finally launch a major revision of the Wilmington crisis.

Zucchino’s book, indeed, owes a great deal to historian Timothy B. Tyson’s extraordinary 2006 exposé, “The Ghosts of 1898,” published in the Raleigh News & Observer, which showed us the price we all pay for events we comfortably leave “long shadowed by ignorance and forgetfulness.”

Tyson’s essay, and the News & Observer’s apology for its pivotal part in fomenting the coup, finally led to the creation of a monument and memorial park in 2008 that directly acknowledges the facts of what happened. Increasingly, North Carolinians and Americans generally are learning this sordid story from the Jim Crow era. Thanks to David Zucchino and the scholars, journalists, and activists before him, the coup has surged from the periphery to near the center of our national story, although today’s Republican vote suppressors have either ignored it or simply do not care to look into this historical mirror. In a pandemic of unending and frightful consequences, mismanaged from high places with astonishing political venality, and in a new age of voter suppression buffeted by widespread protests against systemic racism, we need these lessons more than ever.

Source: NYREV

David W. Blight is Sterling Professor of American History at Yale. His biography of Frederick Douglass, Prophet of Freedom, received the Pulitzer Prize for History. (November 2020)