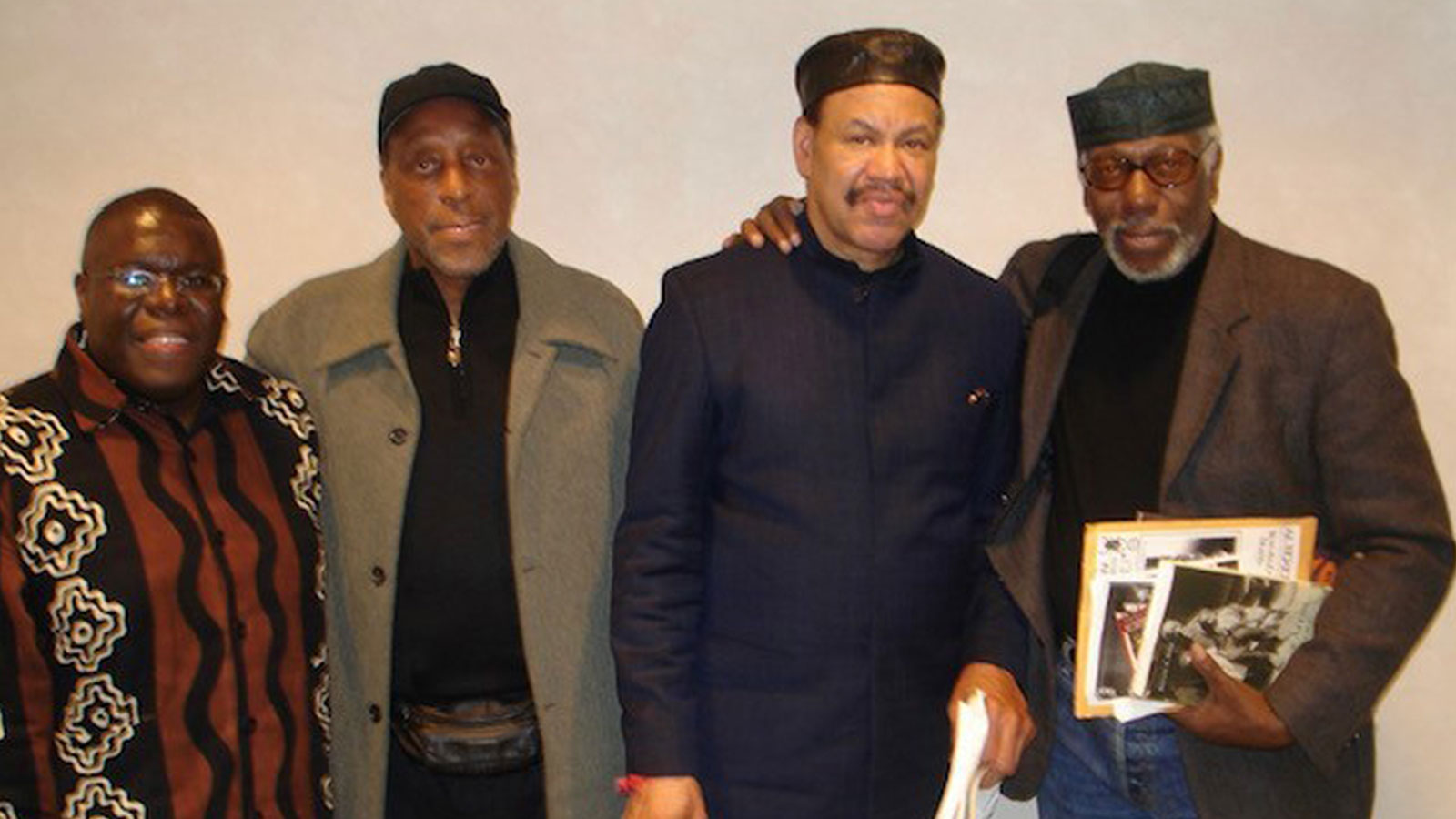

Featured image: L-R: Dr. Anthony Browne, Dr. James Turner, Rev. Clemson Brown, and Herb Boyd At Hunter College in a tribute to Dr. John Henrik Clarke in 2007.

A torrent of compassionate encomiums for Dr. James Turner showered the African American academic community when the word spread that he was an ancestor. Even more occurred last Saturday, Aug. 13, at Bangs Funeral Home in Ithaca, where Dr. Turner resided with his family. It was in this community at Cornell University that he cultivated and expanded his immense knowledge of Africana Studies, sharing it with students, colleagues, and a growing coterie of aspiring scholars. He died on August 6 and was 82.

When Dr. Turner arrived at Cornell in 1969, Black Studies was just emerging from its official chrysalis, but under his guidance—and recasting it as Africana Studies—the program quickly became a significant flagship. He was able to nurture such a process because he paid close attention to his mentors, including the wisdom of Malcolm X. “He was a master teacher,” Dr. Turner said of the great thinker. “You couldn’t listen to him and not come away with something. It was more than charisma, it was the way he was able to use the language of our people and make [them] understand.”

This was just one facet of Malcolm’s teaching that Dr. Turner delivered in the classrooms, at conferences and symposiums, both at home and abroad. The lessons he imparted were always delivered in a slow, well thought out manner, taking care to make sure his students, his audiences knew exactly where he was coming from. And where he was coming from was a place in Harlem where not only Malcolm’s learned voice resonated , but where W.E.B. Du Bois, Dr. John Henrik Clarke, and countless others he had heard on the streets of Harlem.

Dr. Turner was born January 31, 1940 in Brooklyn, New York, but was raised in public housing on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. His father was a laborer. James grew up with the expectation that he would work in the garment trade and industry. That occupation may have been the incentive to attend the High School of Fashion Industries, from which he graduated in 1957, and subsequently being employed at Ripley’s Clothing Store.

Four years later, after a brief stint in the field of social work at Columbia University in their Mobilization for Youth program, he coded data on the activities of youth gangs in the city. But he finally acceded to a higher calling and he and his wife, Janice, moved to Michigan where he earned a bachelor’s degree from Central Michigan University. Then in rapid succession came a master’s degree in African Studies from Northwestern University, a certificate in African Studies from the school’s African Studies Center, and a Ph.D. from Union Institute & University.

As a graduate student at Northwestern University, he, like many highly informed students and activists in the late sixties, was soon as much involved in the classroom as he was on the frontline protesting societal and academic inequities. In 1968, he led more than 100 students in a two-day sit-in demanding the university end its discrimination and improve conditions on campus. Out of this tumult came the creation of the school’s African American Studies Department.

With the momentum Black Studies spreading across the country, James became a prominent speaker. After he delivered a profoundly moving speech at Howard University, the Cornell University administration in 1969, invited Dr. Turner to join the faculty where he became the founding Director of the Africana Studies and Research Center. His appointment was the result of direct action by Black students who demanded that the university support the inclusion of Black Studies under Dr. Turner’s directorship. During his tenure, he created a space for the kind of intellectual discourse and “specialization of expertise” that students and young professionals had been waiting for. His work focused on designing curriculum; individual and group study opportunities; policy development; and recruiting and mentoring cadres of committed faculty who understood the critical importance of authenticity and truth in the continued development of scholarly work on Black life throughout the African Diaspora. The Center became a hub of education and intellectual productivity where generations of scholars and practitioners interacted and thrived. Dr. Turner treasured the relationships he nurtured with students, their families, colleagues, communities and organizations. He was particularly thrilled to meet generations of students from the same family in some of his classes. This was a new venture for him and the school and he let it be known upon acceptance to take the position that it would be one of “the most far-reaching, imaginative and creative programs in the country.” Embodied in this promise was one of the mottos he had adopted from Du Bois, and one that would inform his educational vision for the next generation or two, that “Our objective is to examine the record, clarify, and verify, the complexity and richness of the history and culture of African peoples.”

And this he accomplished without reservation or concession, even after the school on April 1, 1970, just seven months after its inception, was destroyed in a suspected arson attack, David Nutt, wrote in the Cornell Chronicle. Despite the challenges and turmoil, Dr. Turner was unwavering in his commitment, particularly to his students. “Brother James Turner,” said John Higginson, “was a soldier in our army of liberation. He knew when to stand up and when to listen.”

In the words of Dr. Anthony Browne, chair of the Department of Africana, Puerto Rican and Latino Studies at Hunter College, a close associate, said “Dr. Turner’s life was spent in the service to people of African descent around the globe. He was a visionary institution builder who coined the term Africana Studies to reflect the discipline’s Pan-Africanist commitment.”

Dr. Turner in Lynette Chappell-Williams’ estimation was “always a gentle giant and true renaissance man…and a catalyst for change at Cornell, and in my role of advancing diversity, was a true inspiration for continuing the difficult work.”

Some of those burdens will be shouldered by his immediate family who survives him, including his wife, Janice, and his three children, Hassan, Sekai, and Tshaka. A memorial service will be announced at a later date.