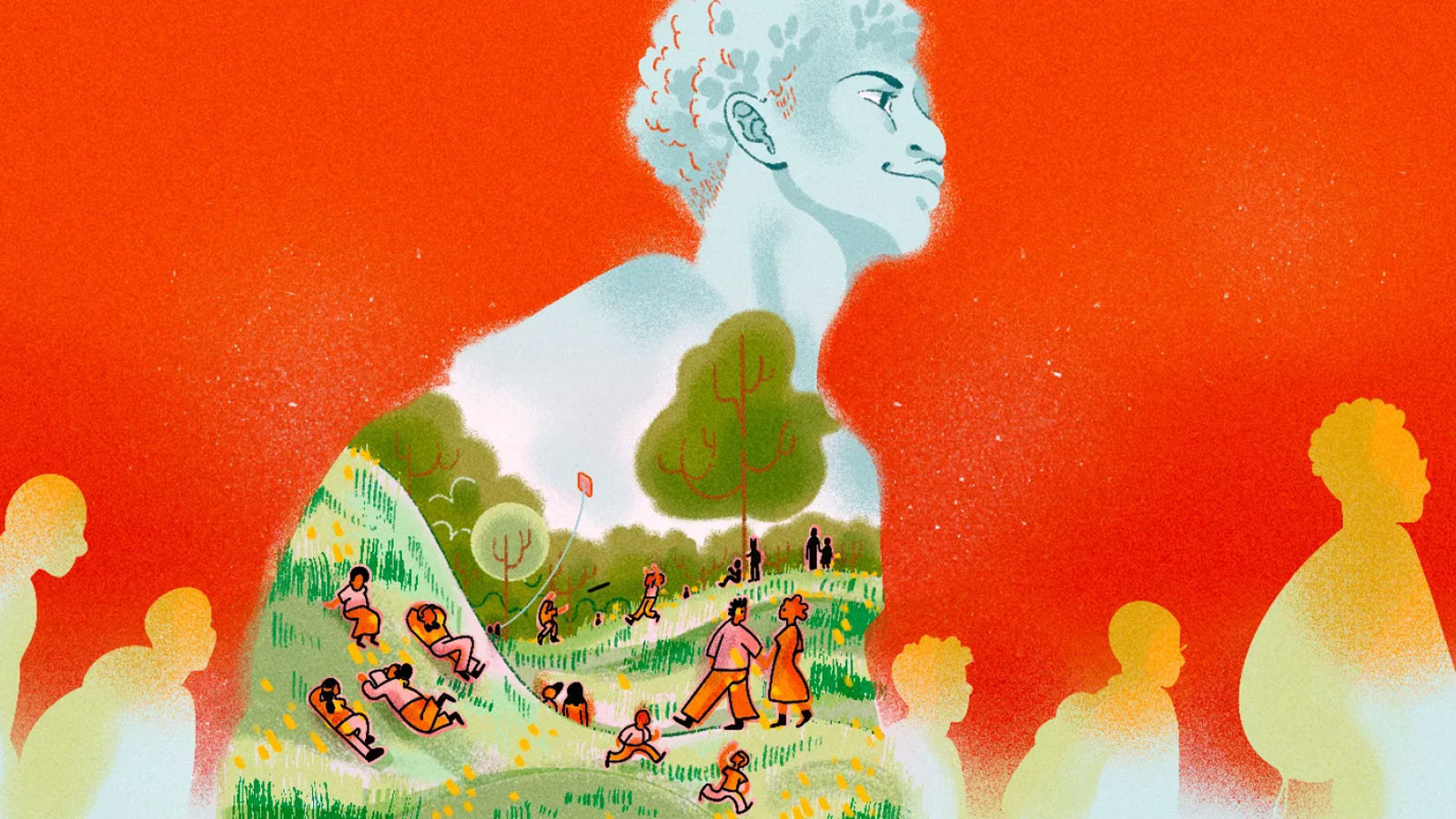

Investing in programs, resources, and physical spaces by and for Black youth is critical to narrowing generationally inherited disparities in wealth, health, and beyond.

By Torie Weiston-Serdan, YES! —

The issue of providing reparations to the descendants of enslaved Africans has become a deeply divisive topic. Sparked in part by the high-profile deliberations of California’s Reparations Task Force, debates over accounting for the wrongs of slavery and systemic racism are taking place in state houses and Congress nationwide. The battle over a legal definition of reparations for Black people is also part of a global conversation about the need to repair and restore a people who have been historically looted, displaced, and exploited. Financial reparations could soon become a reality worldwide.

This debate intersects with a growing grassroots movement to build youth-centered spaces where Black youth leadership is intrinsically tied to a Black freedom dream fueled by reparations owed to their ancestors. Providing spaces for youth power and healing is essential, and while money alone cannot fully remedy racial trauma, investing in programs and resources to support Black youth is critical to narrowing disparities in wealth, health, and beyond. Youth-centered community spaces, in particular, can foster connection, personal growth, and identity development and help mitigate the adverse effects of structural racism—serving as an impactful, nonfinancial form of reparations.

Most cities in the United States have too few youth-centered spaces and even fewer Black youth-led ones, offering a unique opportunity for Black youth to build and thrive in spaces that can be called their own. Some advocates argue that demonstrating to young people that they can play, rest, and experience joy in appealing spaces that they themselves direct is possible through land obtained via reparations. In their view, this illustrates control of one’s fate by using areas as needed without worrying about affordability or displacement. “Today’s Black youth need access to social services, access to financial resources, and a sense of ownership over beautiful land and spacious buildings,” says Steve Vassor, a mentoring and youth development champion based in New York. “They need alternatives to schools, with education rooted in community, to better know themselves. For the sake of their identities, they need affirming spaces filled with love and support.”

One example of a Black youth-led space that embodies a reparative approach to community is the Black Youth Project (BYP) of Chicago. According to its website description, BYP started first as a research project and shifted into a thriving youth-led organization that studies the lived experience of young Black people, amplifies their perspectives, and mobilizes them and their allies to make positive change. BYP has centered Black youth progressive politics, organizing, and narrative change, and has produced preeminent activists and scholars such as Charlene Carruthers, author of the acclaimed book Unapologetic: A Black, Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements. While BYP is a blueprint and a model for Black youth spaces, the fact that it is an offshoot of a University of Chicago institute means it’s still physically housed in a historically white institution.

The Bay Area-based Kingmakers of Oakland (KOO) is a nonprofit organization “unapologetically focusing on Black Boys” that is shifting the educational landscape for Black youth through innovative and African-centered education curricula. Its programs center youth voices, youth-led media projects, and arts education to engage and empower the young people it serves. The organization purchased a building in 2022 for a program called the KOO Labs Design Center and Production House. The purpose of the space and the work happening within is to foster creativity and provide youth with resources to create content with positive and affirming narratives.

According to KOO’s founder and CEO, Christopher Chatmon, the space is dedicated to “supporting and accelerating creativity and imagination.” Chatmon describes his underlying hope for the space as one that will “accelerate content in the areas of music, film, animation, video production, podcasting, and fashion design.” He adds that the goal is “to teach young people workforce development skills, owning your masters, owning your content, and creating passive residual income while still doing other things they want to do.”

What Chatmon describes is a veritable utopia of culture production in which young Black voices are not only creators and purveyors but also owners. Physical space plays a vitally important role in KOO’s ability to do this.

KOO’s future plans include purchasing 200 to 300 acres of wilderness for outdoor education and a space for retreats to remedy the dismal lack of access to African-centered outdoor and rest spaces for Black communities. Groups such as KOO need direct funding and land grants to help them construct permanent transformative spaces tailored to Black youth without relying on traditional, white-led philanthropic institutions.

Investments in groups like KOO, which are proximate to and trusted by Black communities, can align with the restorative spirit of reparations. Chatmon proposes that investments as a form of reparations could help fund the group’s future plans. He says, “We need to leverage reparations money to build parallel institutions that get us thinking from a diasporic standpoint,” adding that such funding could help KOO “to acquire land, to expand our social capital, to increase our net worth, to connect folks throughout the diaspora, to help radically shift our young people’s world view.” According to Chatmon, such investments embody reparations’ true purpose and promise: uplifting and transforming the community.

Youth activists in Charlottesville, Virginia, are also attempting to build Black youth-led spaces by challenging encroaching developers and hoping to purchase a church as a convening and organizing hub in a historic Black area called Dairy Market. Leading an intergenerational campaign against a Charlottesville developer, a group of young Black leaders launched an effort called #RespectTheNeighborsCampaign.

As part of a multiracial and intergenerational movement to reclaim gentrified space, organizers are crafting a proposal to purchase part of the historic area. Zyahna Bryant, one of the campaign’s leaders, believes reparations can help young people secure intergenerational spaces in their communities. “Young people are energized to make spaces that are dedicated to building community in a way that centers the needs and perspectives of youth,” says Bryant.

If Bryant and her fellow organizers succeed, they would be among only a handful of successful cooperative projects that reclaim Black spaces specifically for youth and model radical forms of collective ownership that upend the traditionally capitalist, individualist ownership model. When asked about how reparations funding would be helpful in supporting their endeavor, Bryant responds that “growing up on 10th and Page, the need for intergenerational placemaking has become increasingly clear in order to hold on to some of those elements that have made the neighborhood all that it is.” She explains that, “In order for youth to lead and take up space, we need support. Reparations could be a method for getting the resources in the hands of those who need it the most—young Black leaders.”

There are examples of youth-led projects serving as a form of reparations that have already achieved success. In 2023, the California-based nonprofit Youth Mentoring Action Network (YMAN) purchased a one-acre estate in the Inland Empire in order to transform it into an oasis for Black youth and young people of color. [Full disclosure: the author of this article is YMAN’s chief visionary officer]. The group upended the historical usage of the space; it had only ever been owned by private white families before. The lush property, the Youth Power Hub, is now a dedicated public space for youth liberation. The estate integrates mentoring, wellness, and education with spaces like a garden where young people can engage in garden therapy, a lab filled with computers, music, and video production equipment for content creators, and a wellness room with meditation pillows and blankets. In its first year, the space hosted various groups using it as a retreat within a Black-owned and youth-centered space. Groups like the Black Land Ownership organization demonstrate that Black land ownership is about more than just acreage—it represents cultural power and reclaiming space in the face of historic land dispossession.

When YMAN came across the one-acre estate, the group realized that one of the key ingredients to innovation in youth development is having physical spaces that can be awe-inspiring. According to YMAN board member Tunette Powell, “Giving Black youth beautiful spaces to dream, play, and experience joy is critical in pushing past the survival mode solution that most spaces with a clinical feel tend to offer.” She worries that “Black folx and young people are losing the most ground to forces of gentrification and industrialization. They need their own spaces.”

The concept of land ownership is critical, especially for young people who are under-resourced and living in urban areas that lack spaces with the potential to inspire them. Often, youth have to settle for spaces not designed with them in mind, in locations that reproduce the harm they are already familiar with.

Direct funding for youth-led groups and land access can be a form of reparations or, in the words of author and professor Robin D. G. Kelley, a Black “freedom dream” for Black youth, empowering them to construct permanent, tailored spaces. The organizations working to center youth and to construct youth-focused spaces offer potential templates for building radical Black futures and creating ideal environments for youth enduring oppression, even on a global scale.

Torie Weiston-Serdan is co-founder and chief visionary officer of the Youth Mentoring Action Network (YMAN), a youth power-building organization located in California’s Inland Empire. She currently serves as a board member at The California Endowment, and her work has been featured in Blavity, Forbes, Inside Philanthropy, and Philanthropy Women.

Source: YES!

Featured image: Illustration by Islenia Mil/YES! Media

Watch: How Black youth benefit from dedicated spaces

The racial wealth gap in the United States has been a persistent feature of the national economy, largely because there was never proper compensation paid to Black people for historic and contemporary racial harms. Consequently, Black youth remain disadvantaged compared to white kids, who benefit from generational wealth and other privileges.

In a new piece for the YES! digital series “Realizing Reparations,” youth advocate Torie Weiston-Serdan begins with this context to assert that “providing spaces for youth power and healing is essential, and while money alone cannot fully remedy racial trauma, investing in programs and resources to support Black youth is critical to narrowing disparities in wealth, health, and beyond.”

Weiston-Serdan is co-founder and chief visionary officer of the Youth Mentoring Action Network. She spoke with YES! Senior Editor Sonali Kolhatkar on YES! Presents: Rising Up With Sonali about her story, “Spaces As Reparations for Black Youth.”

Video Source: YES!