The American police are in crisis. Here, we use the term crisis as Thomas Kuhn did in his influential book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.1 It refers to a necessary stage in the process of revolutionary reform. According to Kuhn, “normal” practice—in science or institutions—occurs within a paradigm. The paradigm is the conceptual framework that unites a profession. It helps the community of practitioners identify problems or “puzzles” worthy of the profession’s attention. And it provides exemplars of good practice. Over time, insoluble problems and anomalies arise. Attempts to resolve them within the paradigm fail, and a stage of crisis occurs. The crisis, then, is the crucible from which speculations about new paradigms emerge.

For more than a century, the paradigm that has united the American police has centered on controlling crime and maintaining social order through law enforcement. In fact, the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program was established in the late 1920s to provide a scorecard for this work, which in turn reinforced this paradigm. Today, the terms police and law enforcement are used interchangeably, conflating the profession with a single authoritarian task and preventing us from envisioning the police in a more effective public safety role.

For more than 60 years, the American police have faced allegations of abuse, including over-enforcement (leading to mass incarceration), excessive force, and racial discrimination. The profession has also struggled to find comprehensive solutions to crime and to significantly improve crime clearance rates.2 Since the 1960s, nearly all

police reform efforts in the United States, including presidential commissions, U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) pattern-or-practice investigations, court-ordered consent decrees, law enforcement accreditation, and civilian oversight, have sought to address these issues without fundamentally shifting the underlying paradigm. This has led to the current crisis and speculations about new ways forward, including defunding or abolishing the police. The revolutionary reforms we envision and are currently testing in Baltimore do not eliminate the police or the law enforcement function of the police. Instead, it identifies a desired outcome for all police activity—i.e., strong, safe neighborhoods. The enforcement of laws becomes one of many tools in the police toolbox for officers to use judiciously and strategically in furtherance of this desired end.

Speculating about Paradigms

Over the past three decades, social scientists have examined the relationship between collective efficacy—defined as “cohesion among residents combined with shared expectations for social control in public space”—and the presence of disorder and crime.3 Many of these studies demonstrate that, among neighborhoods with similar characteristics, those with higher levels of collective efficacy exhibit significantly lower crime rates.4 In his 2012 Presidential address to the American Society of Criminology, Robert Sampson, a leading figure in the study of collective efficacy, asked the question “…what role can the police play in building collective efficacy?”5 This is an interesting question, because building neighborhood-level collective efficacy is not closely aligned with the logic of law enforcement.

A concrete example of this occurred in Baltimore, where in 2017 the federal government issued a consent decree after finding that the Baltimore Police Department had engaged in a pattern of discriminatory practices against African Americans.6 By invitation from the city, Morgan State University faculty designed the Police and Community Engagement (PACE) program. It was grounded in an epidemiological criminology framework,7 and involved the police and community members in sustained dialogue on issues of procedural justice, perceived legitimacy of the law, perceived legitimacy of the police, and self-reported willingness to cooperate with the police. Despite positive feedback from participants regarding PACE’s contributions to community safety, the program was not sustained. This is the fate of many non-law enforcement programs in police agencies. They simply do not align with the priorities of the law enforcement paradigm.

We wondered if PACE—and collective-efficacy building programs like it—would be prioritized if the role of the police shifted from law enforcement to helping communities remain safe and strong. So, we changed the typical evidence-based research question from “what works in policing” to “what makes neighborhoods and communities safer, and how can the police help make that happen?”

Neighborhood Dynamics and the Neighborhood Atmosphere

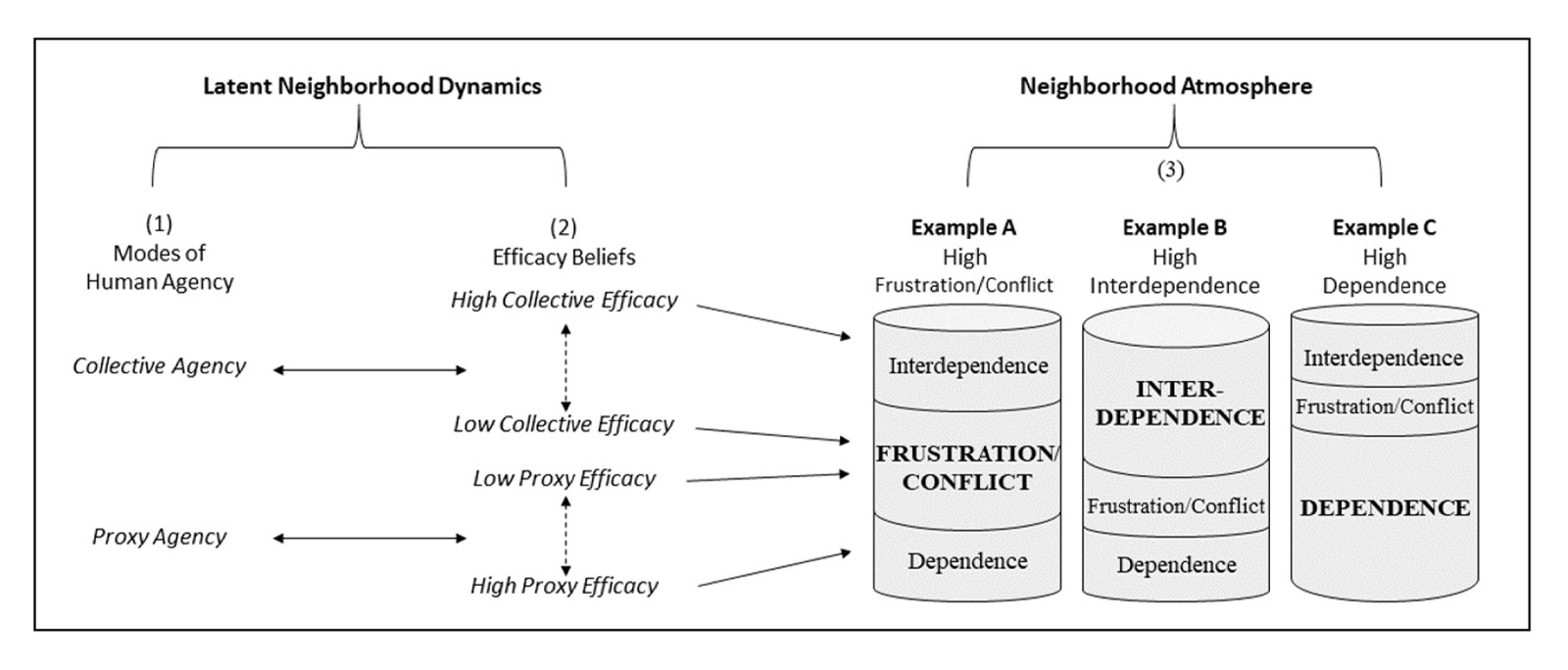

The concept of collective efficacy is tied to a belief in human agency, i.e., the capacity of individuals and groups to intentionally exercise control over the nature and quality of their lives.8 The two modes of human agency relevant to policing are collective and proxy (column 1 of Figure 1). This is where the expectations the police and community have of each other are rooted.

For our purposes, collective agency refers to the police and residents viewing themselves as collaborative partners in public safety. Collective efficacy, then, refers to the shared belief in their collective power to keep a neighborhood safe. On the other hand, proxy agency means the police are expected to control crime and maintain order on behalf of the community. Proxy efficacy refers to shared beliefs about the competence of the police in achieving this task. These dynamic processes are depicted in (1) and (2) of Figure 1. This creates an atmosphere (3) in local neighborhoods that is associated with crime, violence, and many other social problems.

The neighborhood atmosphere is depicted as a receptacle containing varying levels of three substances: interdependence, frustration/conflict, and dependence. Interdependence refers to residents knowing and trusting each other, along with a willingness to work together and with the police to resolve community problems. Frustration/conflict is the degree to which residents avoid each other, do not work well together, or do not trust or like the police. Dependence is the degree to which residents trust the police to act effectively on their behalf. High collective efficacy beliefs create interdependence. High proxy efficacy beliefs create dependence. And low collective or proxy efficacy beliefs create frustration/conflict. The three barrels in Figure 1 represent the varying nature of these three components.

Figure 1. Neighborhood Dynamics and the Neighborhood Atmosphere

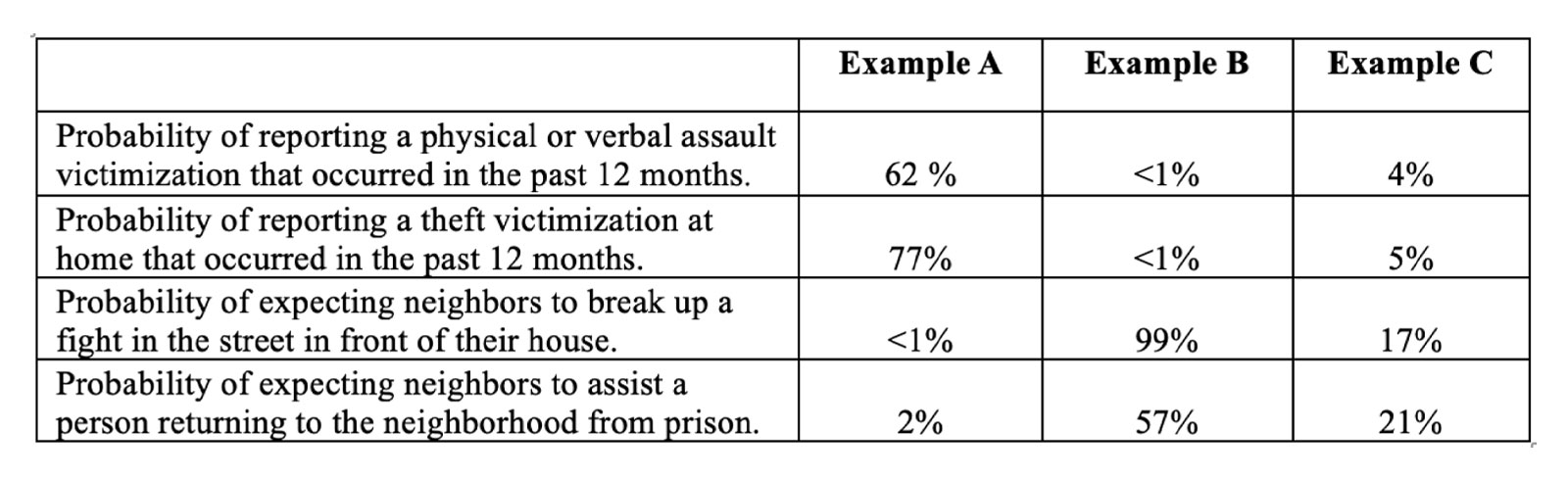

Table 1 illustrates the importance of these ideas, using data from the 2021 West Virginia Social Survey (WVSS).9 The WVSS is a mail survey of households in West Virginia randomly selected from each of the state’s fifty-five counties that asks various questions about community bonds, trust in police and government, and experiences with social, physical, and emotional problems. Using this data, we computed10 for each of the three neighborhood examples from Figure 1 the probabilities of crime victimization within the past year, the expectations of neighbors for informal social control (i.e., responding to break up a fight in the street), and the expectation that neighbors would assist a person returning from prison.

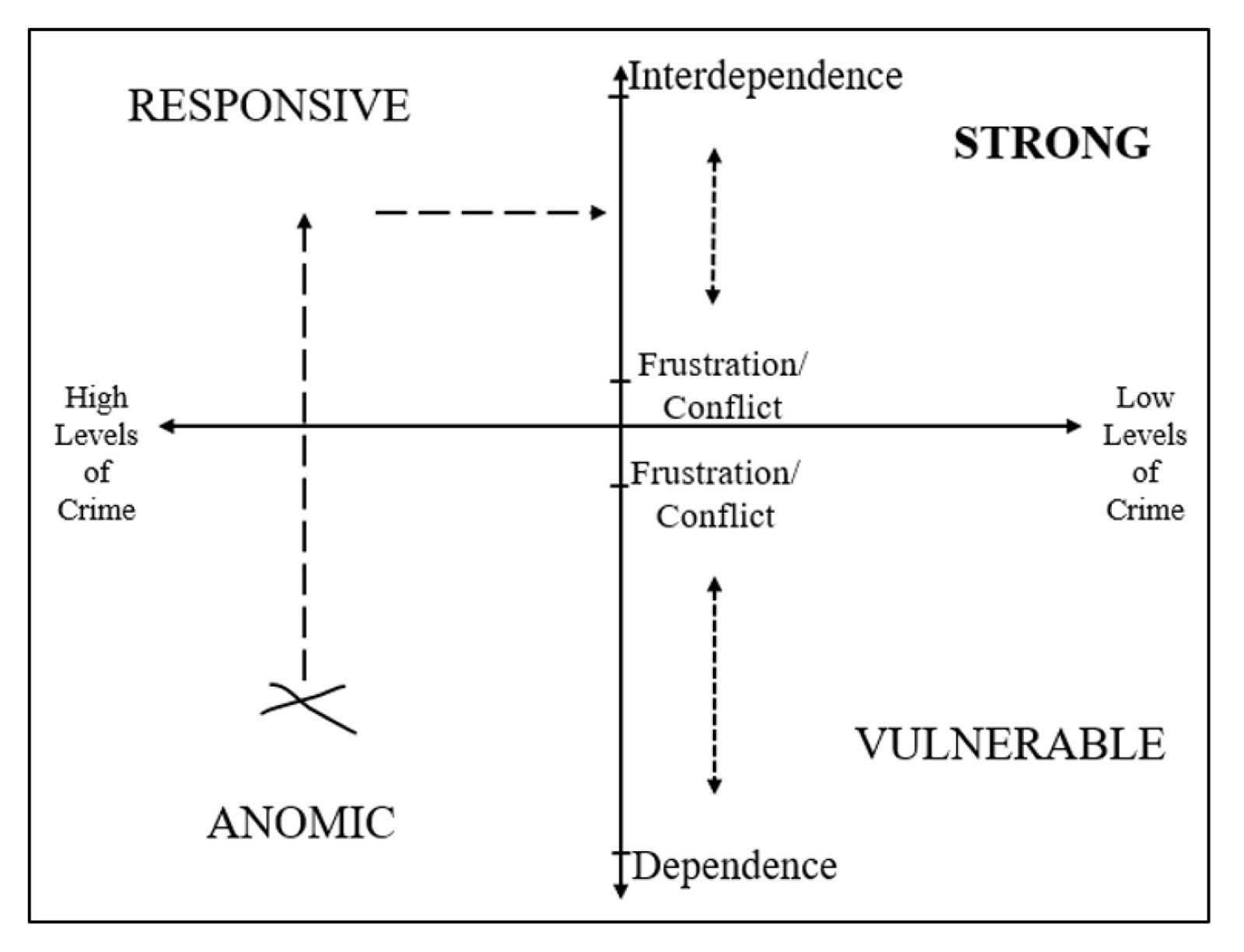

atmosphere on a vertical axis and levels of crime on a horizontal axis. By doing this, four neighborhood types emerge: anomic, responsive, vulnerable, and strong.11 Each of these neighborhood types provides a context for tailoring policing strategies with an eye toward the strong-neighborhood ideal. For example, if the starting place for a police intervention is an anomic neighborhood, a successful policing strategy might include police-community dialogue to discuss ways to secure the area and then mobilize more people and resources. If successful, this would move the neighborhood toward the responsive quadrant. Once there, and with more people and resources involved, comprehensive plans could be developed to reduce crime levels. If

Table 1. Neighborhood Atmosphere: Crime, Informal Social Control, & Prison Reintegration

The analysis reveals the importance of neighborhood atmosphere for public safety. Neighborhoods with high levels of frustration and conflict (example A) are the most dangerous of the three examples. These are places where the risk of crime is high and where residents are least expected to intervene to stop a fight or help someone return to the neighborhood from prison. The opposite is true in interdependent neighborhoods. This is where the risk of crime is lowest, and where neighbors are most expected to act to prevent harm or assist a reintegrating offender (example B). And

dependent neighborhoods (example C) are mixed. The risk of crime in these neighborhoods is low, but the expectation of neighbors to break up a fight in the street or help returning offenders is also low.

Figure 2. Situational Policing

Situational Policing

By broadening our gaze to include both levels of crime and the neighborhood atmosphere, we can envision a new approach to policing, as shown in Figure 2. In Figure 2, we represent the neighborhood successful, this would move the neighborhood toward the strong neighborhood type. This is the desired outcome of police action in a situational policing framework.

A Test in Baltimore

With funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF),12 our team from Morgan State University and West Virginia University is conducting a randomized control trial in four anomic neighborhoods in Baltimore. Two will receive the PACE treatment and two will not. We want to know 1) the impact of the neighborhood atmosphere on crime in Baltimore, and 2) if PACE—cast within a situational policing frame—could successfully change a neighborhood from anomic to responsive. To do so, we employ participatory action research (PAR) methods in our survey work, recruiting and compensating residents as co-researchers. These community members help collect, analyze, and interpret data, and collaboratively generate hypotheses about what might improve local conditions. In this way, the research process itself becomes an integral component of the intervention in the treatment neighborhoods.

At the time of writing, nearly half of the neighborhood surveys are now completed, and the PACE intervention is underway in two neighborhoods. Preliminary findings are consistent with the data in Table 2, showing that neighborhood atmosphere has a significant effect on the risk of crime in our four project neighborhoods. As levels of interdependence increase in these Baltimore neighborhoods, the odds of having been the victim of a violent assault in the neighborhood decrease by 31%, and the odds of having had something stolen at home decrease by 37%. Moreover, as frustration and conflict increase by one standard deviation, the odds of having recently been assaulted with a weapon increase by 231%, and the odds of having experienced a recent theft increase by 58%.

While earlier analysis provides evidence of the importance of neighborhood atmosphere for public safety, it is still too early to tell whether PACE will create higher levels of interdependence and transform neighborhoods from anomic to responsive. We expect to gain more insight in the coming year as we begin the second round of surveys.

Implications for Police Reform

Solutions to contemporary problems in American policing are limited by the law enforcement paradigm itself. By expanding our view of crime control to include neighborhood dynamics, atmosphere, and community outcomes, a different framework emerges that offers new ways to think strategically about police work. Programs like PACE, as well as other community- and problem-oriented initiatives, become useful tools in doing “real police work.” Finally, a framework like this can also help evidence based police researchers by enabling new research questions within varying neighborhood types. It also provides an opportunity to retest the law enforcement programs deemed successful to assess their impact on the neighborhood atmosphere.

Endnotes

- Kuhn, T. (2012). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Nolan, J.J., Ryan, H., Freeman, M. (2025). Police abuse and reform

in America: Examining the facts. New York: Bloomsbury. - Sampson, R. J., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1999). Systematic social

observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology, 105(3), 603–651 (qt. 603). - For example: Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S., & Earls, F. (1997).

Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective

efficacy. Science, 277, 918– 924; Uchida, C.D., Swatt, M.L., Solomon, S.E., & Varano, S. (2014). Neighborhoods and crime: Collective

efficacy and social cohesion in Miami-Dade County. Washington, DC:

National Institute of Justice. - Sampson, R.J. (2013). The place of context: A theory and strategy

for criminology’s hard problems. Criminology, 51, 1–31. (qt. pg. 22). - https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/

justice-department-announces-findings-investigation-baltimorepolice-department. - Akers, T.A., Potter, R.H., and Hill, C.V. (2013). Epidemiological

criminology: A public health approach to crime and violence. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. - Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective.

Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26. - West Virginia Social Survey Reports. Survey Research Center at

West Virginia University. Morgantown, West Virginia. https://survey.wvu.edu/west-virginia-social-survey/reports. - The details of this calculation are presented in Nolan, J.J. & Hinkle,

J.C. (2021). Community dynamics, collective efficacy, and police

reform. In Nolan, J.J., Crispino, F., and Parsons, T. (Eds.) Policing

in an age of reform: An agenda for research and practice. London:

Palgrave Macmillan. - Nolan, J.J., DeKeseredy, W.S., & Brownstein, H.H. (2022). Police

ethics in rural contexts: A left realist consequentialist view. International Journal of Rural Criminology, 7(1), 1–23. - NSF Award Number 2222511.

About the Authors

James J. Nolan, PhD, is a Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at West Virginia University and a former police officer. Natasha C. Pratt-Harris, PhD, is a Professor of Sociology and Anthropology and coordinator of the Criminal Justice Program at Morgan State University. Bishop Kevin Daniels, PhD, is an Associate Professor of Social Work at Morgan State University. Paul C. Archibald, DrPH, LCSW (NY), LCSW-C (MD), is Associate Professor and MSW Program Director in the Department of Social Work at the College of Staten Island, CUNY. Henry H. Brownstein, PhD, is Distinguished Research Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at West Virginia University. Kimberly Glanville, BA, MS, is a PhD Student at Morgan State University and a former police officer. Raiana Davis, MPH, MS, is a PhD Student at Morgan State University.

Source: From the Fall 2025 issue of Translational Criminology, published by the Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy (cebcp.org)