“The modern capitalist world would not exist without colonialism and the drain,” says Indian economist Utsa Patnaik

BRITAIN impoverished India over the course of its colonial rule by a staggering £9.2 trillion, laying the groundwork for modern international capitalism and holding back present-day India’s ability to escape poverty, a leading Indian economist has claimed.

Utsa Patnaik, Professor Emeritus at Jawaharlal Nehru University’s Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, voiced her conclusions in a recently published Columbia University Press essay, based on extensive research conducted into the fiscal relations between Colonial India and Britain during the days of empire.

Between 1765 and 1938, “the drain amounted to 9.2 trillion pounds ($45 trillion), taking India’s export surplus earnings as the measure, and compounding it at a 5 per cent rate of interest,” Professor Patnaik explained in an interview with Live Mint this week.

To put this in context, Britain’s 2018 GDP estimate is roughly £2.3 trillion, meaning that the scale of British impoverishment of colonial India was so vast, that an accurate reparations of the amount drained would collapse the modern UK economy several times over.

Professor Patnaik argues that the key factor was Britain’s control over both taxation revenues and India’s earnings from its booming commodity export surplus with the world, which were used to ward of poverty and starvation in Britain at the expense of the Indian people.

“During Britain’s industrial transition, 1780 to 1820, the drain from Asia and the West Indies combined was about 6 per cent of Britain’s GDP, nearly the same as its own savings rate.” Professor Utsa Patnaik

Explaining the mechanism by which the British Empire accomplished this in an article in the Hindustan Times, Professor Patnaik writes: “Simply put, Britain used locally raised rupee tax revenues to pay for its net import of goods, a highly abnormal use of budgetary funds not seen in any sovereign country.

“The East India Company from 1765 onwards allocated every year up to one-third of Indian budgetary revenues net of collection costs, to buy a large volume of goods for direct import into Britain, far in excess of that country’s own needs. Since tropical goods were highly prized in other cold temperate countries which could never produce them, in effect these free goods represented international purchasing power for Britain which kept a part for its own use and re-exported the balance to other countries in Europe and North America against import of food grains, iron and other goods in which it was deficient.”

When the British Crown took over from the East India Company in 1861, a “clever system” was introduced, according to Patnaik, which saw all of India’s financial gold and forex earnings from its commodity export surplus appropriated and taken into British control. In consequence, “Indians [were] deprived of every bit of the enormous international purchasing power they had earned over 175 years.”

Commenting on contemporary debates in India over what would constitute fair reparations from the UK for its colonial past, Professor Pataik commented in February this year that, were such reparations to accurately represent the amount of money drained, “Britain would collapse; it does not have the capacity to pay even a fraction of what it drained over 200 years.”

The effects of Britain’s theft of Indian wealth were far reaching; despite India registering as the second largest exporter of surplus earnings in the world, after the United States, for the three decades preceding 1929, there was virtually no per capita income in India between 1900 and 1946.

Over this period, poverty, disease and malnutrition were widespread, resulting in an Indian life-expectancy of just 22 years old in 1911.

Not only did the British system impoverish India, Professor Patnaik argues, but was essential to the system of international capitalism we live with today.

“The modern capitalist world would not exist without colonialism and the drain,” Professor Patnaik told Live Mint. “During Britain’s industrial transition, 1780 to 1820, the drain from Asia and the West Indies combined was about 6 per cent of Britain’s GDP, nearly the same as its own savings rate.

“After the mid-19th century, Britain was running current account deficits with Continental Europe and North America, and at the same time, it was investing massively in these regions, which meant running capital account deficits too. The two deficits summed to large and rising balance of payments (BoP) deficits with these regions.

“How was it possible for Britain to export so much capital—which went into building railways, roads and factories in the U.S. and continental Europe? Its BoP deficits with these regions were being settled by appropriating the financial gold and forex earned by the colonies, especially India. Every unusual expense like war was also put on the Indian budget, and whatever India was not able to meet through its annual exchange earnings was shown as its indebtedness, on which interest accumulated.”

As a result, not just Britain but the entire advanced capitalist world of the modern era benefited from the wealth taken from India and other colonies, as Britain itself was too small to absorb the entire drain, resulting in its development into the world’s largest capital exporter, without which the industrialisation and infrastructure development of Europe, the United States and Russia would not have been possible.

“Britain, in particular, morally owes reparations for the 3 million civilians who died in the Bengal famine, because it was an engineered famine.” Professor Utsa Pataik

Despite the impossibility of accurate reparations, Professor Pataik has argued that the advanced capitalist world should recognise its reliance on colonial drain by setting aside a portion of its GDP for unqualified annual transfers to developing nations, with priority given to the poorest among them.

“Britain, in particular, morally owes reparations for the 3 million civilians who died in the Bengal famine, because it was an engineered famine,” Professor Pataik said.

Despite widespread calls throughout Indian politics for some form of reparations for the damaging actions of the British Empire, recent UK Governments have taken an increasingly firm line against such measures.

In 2015, then-prime minister David Cameron ruled out the possibility of reparations for Britain’s role in the historic slave trade during a visit to Jamaica, urging Caribeean countries to “move on.”

That same year, Indian MP former United Nations under-secretary general Shashi Tharoor argued in an Oxford Union debate that “Britain’s rise for 200 years was financed by its depredations in India.”

He continued: “We paid for our own oppression. It’s a bit rich to impress, maim, kill, torture and repress and then celebrate democracy at the end of it.”

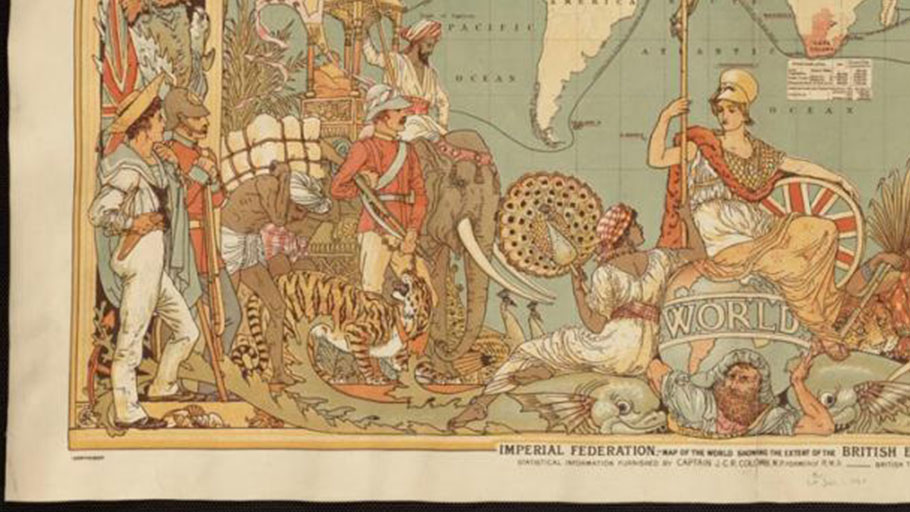

Picture courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center