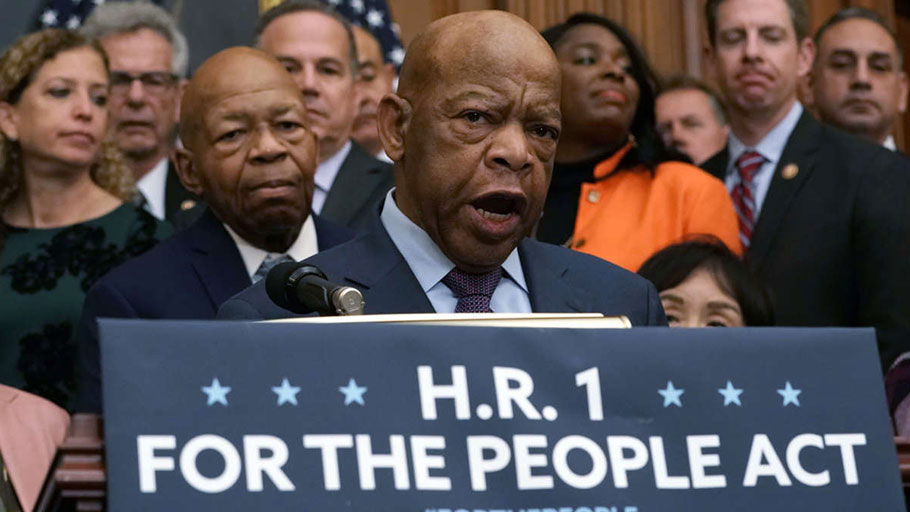

Civil rights icon Rep. John Lewis (D-Georgia) speaks in favor of the For the People Act, a sweeping, pro-democracy bill passed by the House in 2019 that combines measures to protect voting rights, curb Big Money influence, and strengthen ethics rules. (Photo by Getty Images.)

By Chris Kromm, Facing South —

Ten years ago, on a narrow 5-4 vote, the Supreme Court of the United States issued a decision that has reshaped our country’s democracy.

Citizens United v. FEC opened a new era in Big Money influence in politics, fueling a dramatic rise in election spending by super PACs and other shadowy outside groups: According to the Center for Responsive Politics, independent political organizations have poured $4.5 billion into federal elections since 2010, including more than $960 million in spending by groups that don’t have to disclose their donors.

“In our 35 years of following the money,” Sheila Krumholz, the Center’s director, recently said, “We’ve never seen a court decision transform the campaign finance system as drastically as Citizens United.”

Citizens United struck down caps on “independent” election spending by corporations, nonprofits and unions. Limiting donations made directly to candidates can be justified, the court reasoned, because donors can exert dangerous levels of influence. But the court held that political cash flowing to independent groups poses no such threat; in the words of former Justice John Paul Stevens, “independent expenditures, including those made by corporations, do not give rise to corruption or the appearance of corruption.”

Today, the public doesn’t believe that post-Citizens United politics are free of corruption. In fact, growing concern about Big Money’s corrupting influence is one of the few issues that unites voters. A 2018 survey by the University of Maryland found that 88 percent of voters want to reduce the influence of big donors over lawmakers, including 84 percent of Republicans and 92 percent of Democrats. Another 2018 poll in congressional swing districts found that 75 percent of voters believe that “ending the culture of corruption in Washington” is “very important,” ranking it as a higher priority than protecting Social Security and Medicare, or “growing the economy and creating jobs.”

Adding to the broad appeal of tackling political corruption is heightened awareness of how Big Money exacerbates inequality, especially along race and class lines. As a growing body of research shows, most big political donors are white and male, drowning out the voices of the country’s increasingly diverse electorate. What’s more, the skyrocketing cost of elections blocks many lower-income and people of color candidates from running for office.

As Daniel Weiner, an attorney at the nonprofit Brennan Center, noted:

“This is perhaps the most troubling result of Citizens United: in a time of historic wealth inequality, the decision has helped reinforce the growing sense that our democracy primarily serves the interests of the wealthy few, and that democratic participation for the vast majority of citizens is of relatively little value.”

But as concern about Big Money’s corrupting influence grows — including the role our money-driven political system plays in deepening inequality — reform advocates are building an inclusive movement to curb the undue influence of special interests, while connecting money in politics reform to a broader measures to strengthen democracy.

The donor class

The tidal wave of money flooding into politics has strengthened the influence of a narrow elite in our democracy: the donor class. A series of studies in recent years show that, while the voters and population of the South and country are becoming increasingly racially diverse, the class of big donors that shapes politics and policy continues to be overwhelmingly white.

In 2016, the policy think tank Demos released a report looking at the demographics of big political donors, which they defined as those giving $5,000 or more. From 2012 to 2016, 91 percent of these elite contributors to presidential campaigns were white. In the same time period, just 3 percent of high-level presidential donors were people of color; the share of non-white top contributors to congressional races was only 4 percent.

The dominance of white donors has continued into the 2020 presidential contest. An analysis by Alex Kotch and Donald Shaw for Sludge in August 2019 — when there were still 19 Democratic candidates – found that for all but three of the party’s White House hopefuls (Julian Castro, Tulsi Gabbard, and Andrew Yang), more than 85 percent of donors giving $200 or more where white.

Data from the state and local level reveal similar racial disparities in the donor class. A 2015 Facing South/Institute for Southern Studies analysis of North Carolina donors to federal campaigns in 2014 and 2016 revealed that 95 percent of big donors to key races were white, in a state where non-Hispanic whites make up only 65 percent of the population. Another report by Demos found that even in Miami-Dade County in Florida, which has an established and successful Latinx community, only 12 of the 500 biggest donors in 2014 were people of color.

Who donates to elections has real consequences. Donors play a big role in picking and reinforcing which candidates run for office and get elected; a recent analysis found the better-funded candidate wins more than 90 percent of the time. But elite donors also push an agenda that often serves their interests, which is often out of step with the broader public. The 2016 Demos study, for example, found that while 53 percent of people who didn’t contribute to campaigns supported the Affordable Care Act, only 44 percent of elite donors did. “Male donors are less supportive of reproductive justice,” Demos found, “And white donors are less supportive of immigration reform and action on climate change.”

The narrow makeup of the elite donor class also feeds another form of political inequality: who can afford to run for office. The escalating cost of campaigns represents a daunting obstacle to poor and working-class citizens interested in public service, especially women and people of color, who often struggle to gain backing from wealthy white donors. A’shanti Gholar, political director of the Democratic group Emerge America and creator of The Brown Girls Guide to Politics, noted, “Fundraising is going to be different for you because people are not going to see you as a viable candidate because of the color of your skin.”

As the Movement for Black Lives concluded in their 2016 policy agenda:

“The dominance of big money in our politics makes it far harder for poor and working-class Black people to exert political power and effectively advocate for their interests as both wealth and power are consolidated by a small, very white, share of the population … Black candidates are less likely to run for elected office, raise less money when they do, and are less likely to win.”

Building an inclusive reform coalition

Since the 2010 Citizens United ruling, democracy advocates and other allies have responded with a raft of proposals, some aimed at curbing Big Money’s influence and others at reversing the decision itself.

As of last year, 20 states and 800 municipalities had passed resolutions calling for Citizens United to be overturned. A resolution passed in the West Virginia Senate in 2013, for example, supports an amendment to the U.S. Constitution establishing that “corporations are not entitled to the same rights and protection as natural persons,” one of the underlying legal assumptions behind the court’s 2010 decision. Democrats in Congress file legislation each year calling for an amendment reversing Citizens United.

Polls have routinely found the public supports such measures: A 2018 survey showed that three-fourths of voters — including 66 percent of Republicans — back a constitutional amendment overturning Citizens United. But even the most optimistic advocates confess it will be a difficult feat to achieve: Amending the Constitution requires a two-thirds vote in both the U.S. House and Senate, and ratification by three-fourths of state legislatures.

Other reform efforts are tackling key problems in the money in politics system. Since Citizens United, spending by secretive groups that don’t have to disclose their donors has skyrocketed. Many states, especially in the South, have weak laws for disclosure of spending by independent groups.

In California, reformers pushed through a law that requires charitable nonprofits to confidentially disclose to state regulators all donors who give $5,000 or more. The Americans for Prosperity Foundation — the “charitable” arm of the Koch-backed political group Americans for Prosperity, which reported $17.3 million in revenue in 2018 — is challenging the law, a case that will be closely watched by other states.

In North Carolina, reformers are pushing for the state’s strong disclosure laws to be expanded to online advertising on platforms like Facebook and YouTube. While candidates and groups are required to disclose their backing of political ads on television and radio, state laws haven’t caught up to the new digital era. Despite bipartisan backing, a bill introduced in 2019 to close North Carolina’s digital loophole was pulled after pressure from groups backed by Art Pope, a major conservative donor.

Advocates are also pushing for reforms that, while leaving Citizens United intact, amount to major overhauls of how elections are funded.

In 2017, the city council in St. Petersburg, Florida, voted to prohibit spending by foreign-influenced corporations in city elections, and placed limits on contributions to political action committees, effectively abolishing super PACs in local elections. Another 2010 court case, SpeechNow.org v. FEC, drew on Citizens United in holding that federal laws limiting PAC contributions to $5,000 per person shouldn’t apply to “independent expenditures.” That decision was upheld in several appellate circuits, but not the 11th U.S. Court of Appeals, which covers federal cases in Alabama, Florida, and Georgia, opening the way for the St. Petersburg ban.

As John Bonifaz, president of the group Free Speech for People, which worked with local officials to pass the ban, said at the time:

“The City of St. Petersburg is leading the way in the fight to reclaim our democracy. Today’s vote by the St. Petersburg City Council marks a huge victory for the people all across the city who have stood up to demand an end to super PACs and foreign-influenced corporations threatening the integrity of their local elections. This ordinance will be a model for communities throughout the nation on how to fight big money in politics and defend the promise of American self-government.”

Another key reform aims not just to curb Big Money, but to expand the power of small donors. As of 2018, 24 cities and towns and 14 states had some version of small-donor public financing programs, in which small donations from local residents are matched by public funds. North Carolina was a pioneer in small-donor election funding, with successful programs for judges, council of state races, and a pilot city program in Chapel Hill; all were eliminated when Republican lawmakers, many funded by Big Money interests hostile to public financing, took control of state politics in 2013. Experiments in small-donor public financing have been tried in Alabama, Florida, Texas, and West Virginia.

Where small-donor public financing has passed, the results have been striking. Under North Carolina’s judicial public financing program from 2004 to 2012, donations by special interests plummeted from 73 percent of donations received by judges seeking office to just 14 percent. Curbing the influence of Big Money increased court diversity, too: All of the women and African-American candidates for the N.C. Supreme Court used the public financing program, leading to the state’s first female-majority higher court in 2011, and the election of the judge who is now the first African-American woman chief justice, Cheri Beasley.

Across the country, public financing has increased the racial, gender, and economic diversity of both political donors and candidates, lowering the financial barriers to candidates wanting to run for office.

Anti-corruption, pro-democracy

In the wake of Citizens United, perhaps the most promising development has been efforts by democracy advocates to link anti-corruption measures with broader, pro-democracy reform.

In 2019, shortly after taking office, the new Democratic majority in Congress rolled out H.R. 1: For the People Act, a broad package of measures that The Washington Post called “perhaps the most comprehensive political-reform proposal ever considered by our elected representatives.”

The bill was backed by a broad coalition including civil rights, labor, and environmental organizations, which helped build support for passage in the U.S. House, before it was blocked in the Senate. It has also been buoyed by recent polling by the group End Citizens United, which found that not only do the bill’s provisions enjoy strong public support, but packaging the anti-corruption, voting rights, and ethics reform measures together in a sweeping, pro-democracy package has increased voter support for each of the individual reforms.

Inspired by H.R.1, states are looking to pass their own broad-based democracy reform agendas, drawing on public outrage over corruption to shore up support for protecting voting rights, promoting fair districts, and other measures that strengthen the voice of ordinary voters.

Rajan Narang, who runs End Citizens United’s programs at the state level, says the popularity of H.R.1’s approach of linking together various pro-democracy measures holds great potential for advancing reform. Through their polling and analysis, Narang says, “We found that democracy reforms perform strongest as a group. When they’re mutually reinforcing, it helps voters understand that there’s a broader purpose here, to fix our entire system of government.”

This article was originally published by Facing South.