Part 2.

Nana King, in defining his first practice of service, phrases it as “trying to love somebody,” which is a linking of two of the central pillars in his self-understanding and self-assertion in the world. It is important that he uses the humble and humbling phrase “trying to love.” I see that not only as a reflection of the moral modesty Nana King subscribed to, recognizing human frailty and moral failures, but also as his defining “loving” as a continuous effort and in some cases an outright struggle. Here we remember he makes a distinction between liking someone and loving someone or “somebody,” as he says. He concedes that some people are too mean and negative to be liked as a person. But he insists on the Christian concept of loving even an enemy. That is to say, he asserts, seeing all people as images of God and worthy of the highest respect as human beings. He knows that without this respect, this high valuing of others, which he calls love, we cannot and will not serve others in righteous and needed ways.

Nana Martin speaks of serving in his time by also trying “to be on the right side of the question of war.” He speaks here in the midst of the American war in Vietnam and condemns the massive destruction of the lives and the land of the people of Vietnam, the waste of valuable resources better used in the interest of “social uplift,” education, healthcare, housing and other essential needs of the people of America, especially the poor and most vulnerable. Speaking of today, I think he would condemn Russia’s atrocity-ridden invasion of Ukraine, but also criticize the selective morality of defending and funding Ukraine, welcoming its refugees, and denying equal consideration and treatment of needy and deserving peoples here and refugees of color, especially the Haitian people.

And he would call into moral question and condemn the hypocrisy of the hue and cry against the pitiless occupation of Ukraine while practicing and supporting the brutal occupation of Haiti, Palestine, Iraq, Afghanistan, and the savage and genocidal bombing of Yemen. And Nana King spoke of the “cruel irony” of us as a people, still not fully free from the vicious violence of systemic racism, “linked in a brutal solidarity” of a patriotism that supports America’s policies and practices of using “massive doses of violence to solve its problems (and) to bring changes it want(s)” around the world. And he challenges us, as a people, as a self-conscious moral and social vanguard, to reject this and pose a new paradigm of how humans ought to relate in reciprocal respect and mutual benefit.

Nana Martin tells us in his list of practices of service that he wants us to remember him also as one who tried to serve the vulnerable, “to feed the hungry, clothe the naked and visit the prisoner.” For he knows we measure the morality of any person, people or society by how they treat the most vulnerable among us. He ends his list of practices of service by telling us he wants also to be remembered as one who tried “to love and serve humanity” as a whole. Here he calls to mind Nana Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune’s assignment of us to be a moral and social vanguard, with a world-encompassing, world-transforming mission, saying “Our task is to remake the world. It is nothing less than that.” And this is in turn a reaffirmation of Nana Dr. Anna Julia Cooper’s assertion that “We take our stand on the solidarity of humanity. The oneness of life and the unnaturalness and injustice of all favoritisms, whether of sex, race, condition or country.”

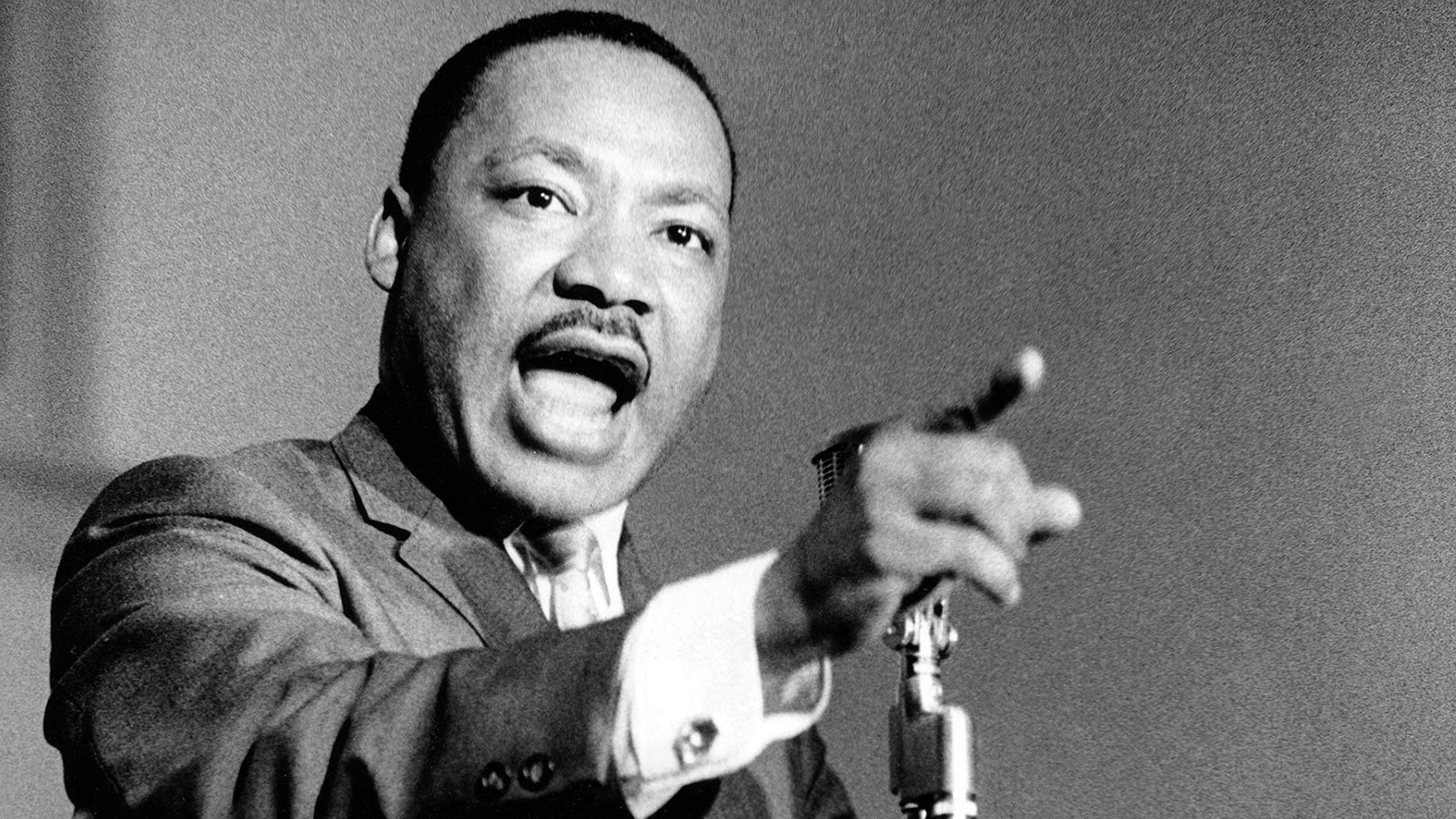

The call to social action and righteous struggle by Nana Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was a call which he combines with companion virtues and challenges. He speaks here of the Black Freedom Movement, our inclusive, righteous and relentless struggle for freedom, justice and equality. Dr. King brings with him the culturally grounded and morally infused audacity to believe the deservedness, justice and possibility of shared life goods for everyone in the world. He says, “I have the audacity to believe that peoples everywhere can have three meals a day for their bodies, education and culture for their minds and dignity, equality and freedom for their spirits.”

But again, we must dare to sacrifice, suffer and struggle to achieve this goal. Thus, he tells us “freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed,” i.e., struggled for. Indeed, he says, with the Movement, “freedom ain’t free.” In fact, he states, “Freedom has always been an expensive thing.” He reminds us that history teaches us, “that freedom is rarely gained without sacrifice and self-denial.” Here, he reaffirms Nana Fannie Lou Hamer’s teaching that in the fight for and toward freedom “you’ve got to fight every step of the way.” And his recognition of the cost of freedom also reminds us of Nana A. Philip Randolph’s admonition that “Freedom is never granted; it is won. Justice is never given, it is extracted.” And each of our ancestor teachers taught the centrality of sacrifice and struggle to achieve these shared human goals. Indeed, Dr. King’s friend, advisor and co-combatant, Nana Bayard Rustin, taught that “the proof that one truly believes is in action,” i.e., in righteous, relentless and transformative action.

In his last speech made in Memphis in support of the struggle of the Black sanitation workers, Nana King senses his impending martyrdom and he assured us of his willingness to sacrifice his life in the cause of the freedom of his people and the radical transformation of America. He noted that there were increased threats against his life and he did not know “what would happen to him from some of our sick white brothers.” And he said, “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do Gods’ will.” Indeed, in doing God’s will, he affirms that he does not fear anyone. And that Divine will is for him, the realization of the shared goods of freedom, justice and equality in the world.

This for him was the realization of the promised land, the concrete lived-experience and enjoyment of the essential and expansive shared goods of the world. Thus, he said that our spirituality and ethics must direct us toward earth as well as heaven, so we can improve the lives of the people in concrete material ways with food, clothing, housing, healthcare, education and economic security, etc. He tells us that “It’s alright to talk about the new Jerusalem, but one day God’s preachers must talk about the (new) New York, the new Atlanta, the new Philadelphia, the new Los Angeles, the new Memphis, Tennessee.” Indeed, he taught that “a religion true to its nature must be concerned about man’s social conditions,” not simply their souls, but also with “the social and economic conditions that scar the soul,” of the people, especially those “that damn them, strangle them and cripple them.” Any religion that ignores these conditions is “a moribund,” “dry-as-dust,” self-deceptive and decadent religion.

He notes that given the radically evil people stalking him, he might not get to this promised land of freedom, justice and equality for all, but he assures us that “we as a people will get to the promised land.” However, as we say in Kawaida, he and all our ancestors will get there, when we as a people do. For they live in us and will experience true freedom, real justice, and genuine equality when we do.

He ends, of course, with the practice we must engage in to achieve the promised land. He lists as indispensable: unity, institution building, financial discipline, economic boycott, a renewed readiness and a greater determination to stand up, struggle, win and continue to “move on in these powerful days of challenge to make America what it ought to be.” And in this radically transformative practice of achieving this vital goal of inclusive shared good for the world, Dr. King urges us to bear in mind that there is no alternative or substitute for morally compelling service, dangerously unselfish sacrifice, and courageous and uncompromising struggle.