Xiomara Castro’s administration won’t have it easy: Corrupt networks permeate every branch of government.

You could hear the shouting inside the Buenos Aires voting center from almost a block away. It was nearing 6 PM on November 28, and arguments began spilling out from the school-turned-polling-place onto the street. In this poor neighborhood in Tegucigalpa, the vote facilitators, who belonged to the ruling right-wing National Party, were preventing voters from casting their ballots. Just minutes remained before the cutoff for the presidential elections. Many had been waiting in line since the morning.

During the last election in 2017, the National Party appeared to be losing until a countrywide power outage took down the voting system. When electricity returned, the ruling party had inexplicably gained the lead. The election was condemned internationally for widespread voter fraud. Residents weren’t going to let an election be stolen again.

“¡Cachurecos!” the crowd jeered, using the pejorative for supporters of the ruling party. “They’re all Cachurecos! They won’t let us vote!” Over a dozen soldiers with M-16s loitered about the building. Outside, police with automatic weapons guarded the metal door, and a truck full of military police in riot gear rolled past. Many here were not allowed to vote, and throughout the country, monitors documented election irregularities.

But it didn’t matter. As the news filtered in, the crowd inside the voting center grew excited: Xiomara Castro—a self-proclaimed democratic socialist and the wife of Manuel Zelaya, a leftist former president ousted in a 2009 coup—was beating Nasry Asfura, right-wing candidate for the National Party and close associate of the current president, Juan Orlando Hernandez.

Before the vote, many were anxious: Upscale businesses boarded their windows in anticipation of violence. Inside the Buenos Aires voting center, a group of young men told me that they were ready to construct barricades and fight the military police if they thought the election was being rigged.

Instead, unease turned to celebration as it became clear Castro would win. Nearly a thousand people gathered in front of Castro’s Liberty and Refoundation (Libre) party headquarters to celebrate, and fireworks exploded over Tegucigalpa into the early hours of the morning.

“This has been the chronicle of a death foretold of a narco-dictatorship here in Honduras,” Siloe Rey, one of the many at the Libre offices, shouted over the fireworks. “It’s done, and they’re going. Honduras is finally going to go forward.”

Honduras had been ruled by three successive right-wing presidents since the 2009 coup, the last two of whom US prosecutors had labeled likely state drug traffickers. The National Party siphoned money from the public health care service into election campaign funds, failed to respond to natural disasters, and formed elite military police units accused of human rights abuses. Poverty levels are the second highest in the hemisphere behind Haiti. These accumulating crises caused migration to spike. The number of Hondurans apprehended at the US border increased from 100,000 in 2018 to over 250,000 in 2019.

“Hondurans had never felt hopeless before [the 2009 coup],” said Farrid Sierra, a high school teacher in Comayagua. “There was always poverty, but people felt like they would make it, that they would be all right. But in these 12 years, you would see caravans of your brothers and sisters leaving, people saying, ‘We’re leaving before we’re going to die here.’”

So deep was the distrust that until Castro’s victory was official, people in Tegucigalpa waited for something to go wrong—for the voting system to “glitch” or for the military, long favored by the National Party, to emerge and launch another coup.

“A lot of us had a lot of fear there would be another fraud,” said Daniela Muñoz, a feminist activist from Tegucigalpa. “Many people even bought food to last for several months, because people knew there could easily be total chaos in the country.”

But Muñoz added that Castro’s win “represents a victory for all of Honduras’s women, because it means that we’re retaking spaces in society that historically men here have stolen from us.”

Castro’s political plans have remained somewhat vague, but a significant number of her policies entail rolling back the legacies of right-wing rule. She has proposed a constituent assembly to rewrite the Constitution in order to make it more inclusive, and has said she wants to loosen Honduras’s draconian abortion laws. She has also suggested strengthening diplomatic relations with Beijing. Notably, she has said she will reverse the imposition of Employment and Economic Development Zones, the quasi-autonomous corporate enclaves that many Hondurans consider to be a way of selling off national sovereignty.

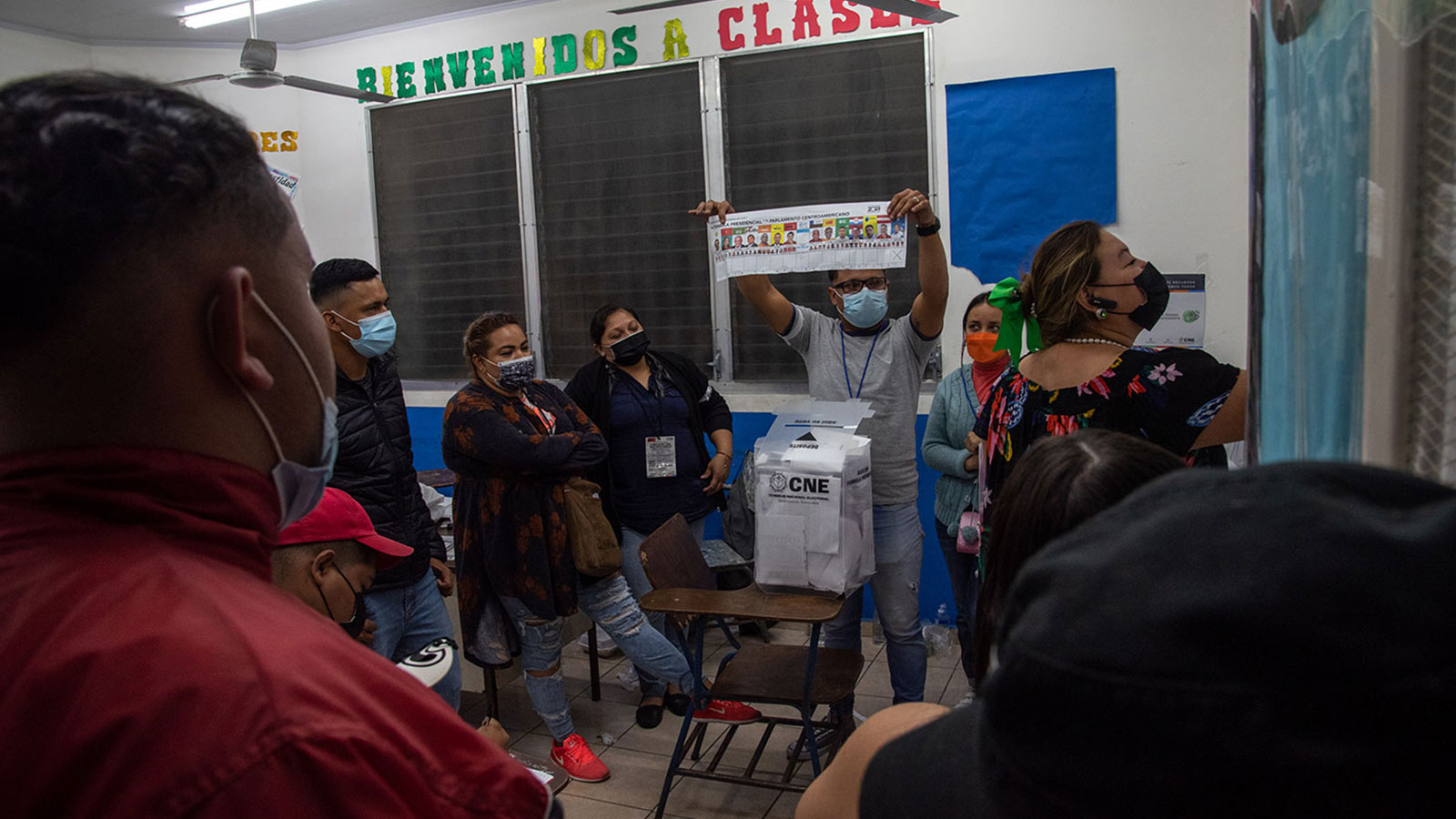

A poll worker displays a finished ballot to voters in Tegucigalpa, Honduras. (Seth Sidney Berry)

It wasn’t clear that Castro had a chance to win until several other opposition candidates decided to support her. Asfura, the National Party candidate, held a narrow lead until Salvador Nasralla, the popular liberal candidate and TV presenter from whom the election was stolen in 2017, threw in his lot with Castro. When I interviewed Manuel Zelaya in 2019, he said that the weakness of the Honduran left was that it lacked the organizational capacity of the National Party, something that would only be overcome if the opposition parties united. Two years later, just downstairs from where we spoke, his wife walked out to a crowd of thousands and a flutter of camera lenses to announce her victory in the presidency. Zelaya had been right.

The Castro government won’t have it easy: Corrupt networks have been entrenched for decades and permeate every branch of government. Hilary Goodfriend, a journalist and doctoral researcher from the National Autonomous University of Mexico, told me that the 2009 election of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, the leftist guerrilla organization turned political party in El Salvador, is an important precedent.

“One of the clearest lessons from 2009—both from the coup in Honduras and FMLN in El Salvador—is that executive power is not the same as taking power, capital P,” Goodfriend said. She explained that the Salvadoran right’s control over congress, the courts, and much of the media constrained and destabilized the FMLN. She expects Libre will face similar challenges.

Goodfriend said it’s a difficult moment for any left-of-center government to come to power in Central America. Many leftist governments depended on high commodity prices to finance social spending, but those prices plummeted after the 2008 financial crash. To stay in power, Castro will likely be forced to negotiate and broker agreements with transnational capital. Nonetheless, Goodfriend said, “history has already been made by the fact that Honduras elected its first woman president, and that that woman was the wife of the democratically elected president of a man ousted in a coup.”

LIBRE party supporters celebrate in Tegucigalpa, Honduras after their presidential candidate, Xiomara Castro, was leading in the first polling results. (Seth Sidney Berry)

Jose Carlos Cardona, a Honduran historian and member of Libre, emphasized the uncharted political territory Castro will have to traverse. “Our country has never been governed by the left,” he said. “The narrative of the elites will be to blame us for every minute error, and, above all, make the country believe that the crisis we’ve inherited is our fault.”

I heard repeatedly that people hope the Castro administration will provide an opportunity for the United States to alter its relationship with the country, which many Hondurans say remains asymmetrical and exploitative. “The US continually dictates whatever goes on in this country,” said Audrey Majomar Lomas, a business owner from Tegucigalpa. “Nothing gets done without the embassy’s approval.”

Paola Raquel, a Honduran student currently studying in China, pointed out that Castro’s interest in strengthening diplomatic relations with Beijing could allow Honduras to demand a more balanced relationship with the United States: “The US will definitely want to help Xiomara’s government [because of that], and have good relationships to end drug trafficking.”

For anyone who opposed the National Party—and it wasn’t just the left; the last 12 years of misrule created enemies across the political spectrum—the election of Castro was an emotional event. On a roundabout in front of a gas station the night of November 29, more than a hundred residents parked their cars, danced, waved red Libre flags, and sprayed each other with champagne bottles. It was a scene that repeated itself on the streets hundreds of times across Tegucigalpa over the past week.

Emanating from someone’s car was the 2017 song “JOH, Es Pa’ Fuera Que Vas,” whose syrupy folk rhythm became part of the soundtrack of resistance to the government. The song about JOH, or Juan Orlando Hernández, translates to:

I’m finally leaving my country

I can’t stay any longer

Because if I decide to stay here

I’ll probably die of hunger.

JOH, you are going away!

JOH, you are going away!

Jalvin Sandoval, a teacher from Tegucigalpa, smoked a cigarette on the hill above the party, overwhelmed by the National Party’s defeat: “All of this right now grows out of the suffering we’ve lived through since the coup d’état. They humiliated the people, they mistreated them. This vote [for Castro] was for all of the deaths since then.” he said through tears. “I finally feel free.”

Source: The Nation

Featured image: Libre party presidential candidate Xiomara Castro acknowledges her supporters after general elections, in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, on November 28, 2021. (Photo by Seth Sidney Berry / SOPA Images / Sipa USA)