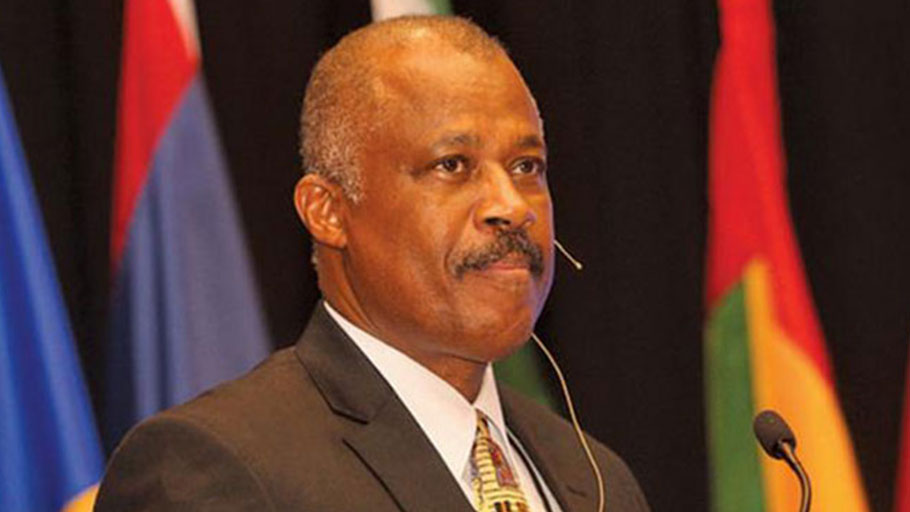

By Sir Hilary Beckles —

Circumstances are rapidly maturing that are demanding our conception of the need for both a new style International Monetary Fund (IMF) and a 21st century post-IMF Caribbean economy.

The elements of the regional dialogue are coming together. They might constitute at this time a blurred image of an alternate Caribbean economy, but they are calling attention to the growing regional interest in a serious focus upon economic sustainability and resilience, and nation building — phase two.

The growth in social and economic inequality across the region in recent decades under IMF tutelage has been identified as a major concern. The recent United Nations Development Programme Caribbean Economic Report tells the starkest version of the story. It shows that while approved fiscal and financial arguments, and corresponding analytic tools, can explain the significant upward social mobility of the immediate post-independence, pre-IMF period, we seem impotent to prevent and understand the consequences of the daily descent into poverty from the middle class since the normalisation and domestication of the IMF.

The Caribbean is not only experiencing the systemic erosion of earlier social mobility gains, but the eruption of a new mental construct in which more citizens, seized in the grip of economic decline, are focused upon “getting out” and “getting even” with the nation.

Citizen versus State is emerging as a primary political feature of the IMF-ruled Caribbean. More citizens are feeling abandoned by the State-IMF alliance and consider it, in some places, an opposition force. We are seeing this anti-nation sentiment playing out in our cricket culture, and the deepening conflictual nature of urban living.

The sustainability of the nation seems imperiled without either violent repression or IMF reinforcements. This circumstance called into question the role of the IMF in the future of Caribbean democracy. For sure, the public perceives that IMF official thinking and tutelage place it on the battlefront where the social effects of its fiscals are fiercely felt.

Either way we look at it, IMF economics, while desired and accepted for macro stability, continue to problematise how the propertyless majority is marginalised in the economy they are keenly ready to kick start.

In effect, then, while we have effectively put in place IMF-inspired “Economic Czars” to drive the economic growth agenda, a strategy to be publicly supported, we are also desperately in need of “Social Czars” to keep the bottom from dropping out of democracy ideal.

To prevent this, the IMF top-down fiscal focus should be accompanied by an indigenous “middle out” and “bottom up” economic vision that sees social growth and a prerequisite for, rather than a consequence of, economic growth.

Where will the new entrepreneurship come from to stabilise our economies and lay the foundations for innovative, competitive industry drivers in the next two decades? The elite economy will continue to hold its own and this is necessary to keep structures and instructions viable. However, the global lessons of recent decades show that the middle and bottom have greater creative energy for the economic uplift that is required.

In addition to this there is the monumental matter of the IMF not wishing to bend its ear to hear of the colonial mess the region has inherited from European wealth-extractive colonialism. Neither does it wish to hear of the reparatory role these developed countries have a moral and legal duty to play in the enormous cleaning up task that has overwhelmed the region.

The IMF proceeds on the basis that Caribbean economies began in 1962 when Jamaica led the path to independence. It does not wish to know of inherited structures and values. As the fiscal and financial voice of these developed nations it might not be able to unblinker itself.

It is our duty to tell it over and over again that the interface of history and economics has dealt the region an awful hand. And, despite our noblest efforts, cleaning up of colonial debris is overwhelming us.

When Sir Arthur Lewis stated in 1938 that the 200 years of unpaid slave labour Europe took out of this region must be accounted for, and considered a debt to be paid, he had good reasons to imagine that institutions of the future, such as the IMF, would have taken this reality on board. This was not to be.

So here we are. A holistic Caribbean development model, post-IMF, has to be imagined as we are currently spinning in mud and going nowhere very fast. There is room in future thinking for a revised 21st century IMF. The one we have at the moment is still embedded in post-colonial thinking that sees the new nations of the Caribbean as places to be tightly policed for their independence audacity.

Everywhere in the Caribbean is now at risk on account of current IMF development thinking. The region sought to convert its colonials into citizens by spending on health, education, urban development, that is, cleaning up the colonial mess they did not create. The IMF demands that such entitlements are beyond its means, and has no policy framework to facilitate social and economic growth simultaneously.

But should a new, revised, 21st century IMF not be an advocate for a Marshall plan for the post-colonial Caribbean? Should a new, more relevant IMF not be a facilitator of a reparatory approach to economic growth with social growth?

The IMF as we know it today might consider itself fit for purpose but the truth says something more — that by failing to fathom the real depth of the inherited Caribbean economic problem it is at best a band aid operation rather than a growth generator. As the young people would put it, “I am just saying.”

Professor Sir Hilary Beckles is vice chancellor of The University of the West Indies