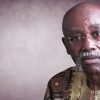

Obama reminded his audience at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign that the current troubles “did not start with Donald Trump. He is a symptom, not the cause.” Photograph by Scott Olson, Getty

By Jelani Cobb, The New Yorker —

One hazard of the trolling that the United States has been subjected to from the White House for the past twenty months is that even the most alarming patterns can be hard to discern, and the most prominent dots impossible to connect. Yet a seemingly different pattern preceded the speech that Barack Obama delivered on Friday, at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, in which he sharply rebuked Donald Trump and the forces that had created his Presidency. Six days ago, the sitting President was obliquely criticized by two former Presidents and the daughter of a deceased senator. Then, excerpts from “Fear,” a new book by Bob Woodward, were released, highlighting the extreme disarray in the White House and the disregard with which Trump’s aides view him. Within a couple of days, a “senior official” in Trump’s Administration had published an anonymous Op-Ed in the Times,detailing the steps that he or she said that a group of officials in that Administration have taken to rein in Trump in an attempt to avert disaster. Meanwhile, in a move that can only be considered corporate counter-trolling, Nike made Colin Kaepernick the face of a new ad campaign, following Trump’s months-long tirade against Kaepernick and the N.F.L. players who followed his lead in kneeling during the national anthem. Viewed in this context, Obama’s acerbic condemnation of Trump seems less like a departure from his policy of remaining outside the political fray—though it is that—and more like the logical culmination of a series of events displaying just how poorly Trump is regarded in many quarters of American life.

Stumping for Hillary Clinton in 2016, Obama frequently criticized Trump without deigning to utter his name. He didn’t mention him by name at John McCain’s funeral, either. But he did name Trump at Urbana-Champaign—twice. Obama reminded his audience of college students that the current troubles “did not start with Donald Trump. He is a symptom, not the cause.” He added, “He’s just capitalizing on resentments that politicians have been fanning for years, a fear and anger that’s rooted in our past but is also born out of the enormous upheavals that have taken place in your brief lifetimes.” And he noted that the threat to democracy “doesn’t just come from Donald Trump”—a formulation that suggests there may be multiple threats, but the current Commander-in-Chief is certainly one of them. Obama went on to ridicule Trump’s inept handling of Charlottesville—“We’re supposed to stand up to discrimination, and we’re sure as heck supposed to stand up clearly and unequivocally to Nazi sympathizers. How hard can that be?” He also said that the current state of affairs was “not normal,” described some of the goings on in the White House as “crazy,” and bluntly announced that we are living in “dangerous times.” As with the speech that Obama delivered in July, in Johannesburg, in which he began by explaining the grand narrative of twentieth-century history and the emergence of the Atlantic order, Obama opened his remarks in Illinois with an overview of the forces that, over time, had shored up and expanded American democracy. Throughout his Presidency, Obama tended to speak of contemporary problems in the context of history, but this time he sounded a little like an engineer who is shocked that he has to explain why it’s a bad idea to knock down a load-bearing wall.

Jason Stanley, a professor of philosophy at Yale, has just published “How Fascism Works,” in which he advances the argument that Fascist politics need not accompany a Fascist state or the rise of a Fascist party; they can exist in the context of democratic forms of government. Fascist politics bear particular and notably contradictory hallmarks: ideas of equality are used to cloak discrimination; demands for “law and order” camouflage growing corruption and official lawlessness. Those descriptions are increasingly applicable to the current state of affairs in the United States, and, more extraordinarily, they mirror Obama’s comments at Urbana-Champaign. “Demagogues promise simple fixes to complex problems,” he said. “They promise to fight for the little guy even as they cater to the wealthiest and the most powerful. They promise to clean up corruption, then plunder away. They start undermining the norms that insure accountability, try to change the rules to entrench their power further. And they appeal to racial nationalism that’s barely veiled, if veiled at all.” Obama did not say the words “Fascism” or “authoritarianism,” but his indictment of Trump and Trumpism was no less severe for it.

Obama’s own route to the Presidency was paved by his image as a purveyor of hope. Eight years in office familiarized the public with other aspects of his personality—a cerebral statesman, a sombre fellow-mourner in Newtown and Charleston, a chief executive whose faith in American better angels sometimes qualified as naïveté. But hope remained the core theme of his public pronouncements. The emergence of Donald Trump as a political force brought out another side of the first black President, one that spoke in increasingly dire tones about what was at stake in the 2016 election. That Obama fell silent on the morning after Trump was elected. We have not heard much from him in the nearly two years since he left office, leaving some to wonder if the former President quite shared their alarm at the inscrutable, bizarre behavior of his successor. What did the man whose success in public life was a product of his fierce allegiance to the idea of hope make of a man who both fixates on catastrophe and seems frighteningly prone to create one?

In Illinois, Obama finally and decisively answered that question. He was there to encourage students to vote, to become active in matters that affect them directly, and to believe in their own power to affect change. But for those students it was equally important that someone whose life has been a testament to American possibilities publicly endorsed the widespread concerns about American peril.