By Rev Jim Conn

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Here at the end of President Obama’s final term in office, we seem to be having the national conversation about race that he called for at the beginning of his candidacy in 2008. That this dialogue coincides with the opening – at long last – of a museum on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. dedicated to the African-American experience, certainly offers us another opportunity.

But so does this presidential race, in which Nixon’s dog-whistle slogan of “law and order” has been transformed into a generalized hostility toward the Other – toward the nonwhite, nonmajority, nonaffluent, nonconventional people of this country.

In this time of polarization, there may be only momentary snapshots of what dialogue might look like for Americans, but apparently, it’s the best we can do.

I am thinking about Gabby Douglas, the young African-American woman on the Olympics’ American gymnastics team who was accused in the media of making some sort of statement by not putting her hand over her heart during the national anthem after receiving her gold medal. The pictures that I saw showed a 19 year old ecstatic after her triumph. Instead of getting that moment of glory, she got called out for it.

Fortunately that bit of manufactured controversy was overshadowed just days later by the arrogance of a white Olympics swimmer, Ryan Lochte, and his pals who got involved in a gas station fracas while in a state of alcohol-induced bravado and then concocted a story about being robbed by gunmen posing as Rio de Janeiro cops. So America felt embarrassed by one of its shining knights.

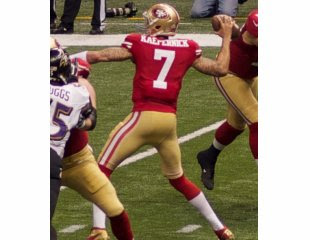

But just in time to shift our focus, Colin Kaepernick, a San Francisco 49ers quarterback, decided to sit through the national anthem to protest violence against people of color. “Everybody knows what’s going on, and this sheds more light on it,” he told reporters. At a subsequent game, a couple of L.A. Rams players raised their right fists during the anthem also.

Recently my wife and I saw a revival of A Raisin in the Sun, Lorraine Hansberry’s stage classic that debuted on Broadway back in 1959. The story centers on a family in which an insurance claim brings enough money for a down payment on a house. The best one they can afford sits across the line separating a black community from a white one. Despite the threat they know will be real, they decide to move. In the 1950s that was a courageous sign of hope against reality. It remains so today because we have not had that national dialogue.

These are just snapshots. They are not the extended conversation the president called for, and there won’t one be unless people keep pushing for it. Which is why the Movement for Black Lives coalition and consistent, local actions such as North Carolina’s Moral Mondays matter so much. Without continual pressure and public presence, these singular actions become a blip on the radar of American consciousness.

As momentarily powerful as they may be, nothing substitutes for real, sustained interaction between, and among, people from various racial groups. Projects like the Alabama-based Southern Poverty Law Center produce anti-bias workshops and materials that help teachers and youth workers cross divisions and respond to hate. The Long Beach-based California Conference for Equality and Justice – what my generation knew as the National Conference of Christians and Jews – focuses on the classroom. They know that diversity in the learning context contributes to child development. They also know that effectiveness requires intentional, consistent cross-racial conversations as well as actions.

One of my mentors in Los Angeles, the Rev. James Lawson, teaches students the power of nonviolent change and the value of cross-racial actions. Lawson trained the Nashville students for their desegregation campaign in the late 1950s, and Martin Luther King Jr. leaned on him for nonviolent strategies. Lawson has taught L.A. labor leaders and union members, because, as he puts it, we have an “unfinished agenda” of racial and economic justice in this country.

In our various enclaves, separated by racial, cultural and socio-economic divides, we lose touch with one another. We do not know one another. As our eyes glaze over from an overdose of spectacle, we do not see the divisiveness we perpetuate just by our passivity. Which is why a museum on the National Mall dedicated to the African-American experience – from slavery to high culture – carries such importance. It helps us remember what tasks as a nation – as people – that we still need to complete. A national conversation is one of them.