By Keith Magee —

Writing to fellow clergy from a Birmingham Jail (The Negro Is Your Brother), Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. – gravely concerned about all who were poor and experiencing inequality – said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

The world, especially, America, will pause this weekend to honour Dr. King’s 90th birthday and his life as a global humanitarian. Would not the greatest birthday gift to share be to truly identify the other as our brother, sister, family? How does one really love and heal a world if they don’t see their neighbour as themselves?

Let us explore the world’s events in this regard. The global crisis of the poor has affected the consciousness of both the UK and America. The UK has wrestled to the ground Brexit with no deal.

Meanwhile, America is in waiting to determine whether the one who was deemed the “White hope”, will be exposed as a traitor. And he remains in a temper tantrum as the government remains shut down.

This mutiny is because, from former U. S. President Barack Obama to former UK Prime Minister David Cameron, few seem to adequately identify the group that is rapidly becoming visible among the least of these. The poverty data of the U.S. Census Bureau reported, on September 12, 2018, that roughly 12.8 million America children lived in poverty in 2017, with 4,026,000 being White. Likewise, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation report of December 4, 2018, indicates there are 4.1 million children living in poverty in the United Kingdom with 1,271,000 of them being White.

In the book, “Black Reconstruction in America”, W.E.B. Du Bois introduced the concept of the psychological wage. Du Bois noted that while White labourers received a low wage, “they were compensated in part by a sort of public and psychological wage.” They were given, “public deference and titles of courtesy because they were white.” I’m not so sure that, in today’s reality of White, having the access to public parks, pools and water fountains matters so much; when they, along with other non-white groups, are equally striving to feed, clothe and house their children.

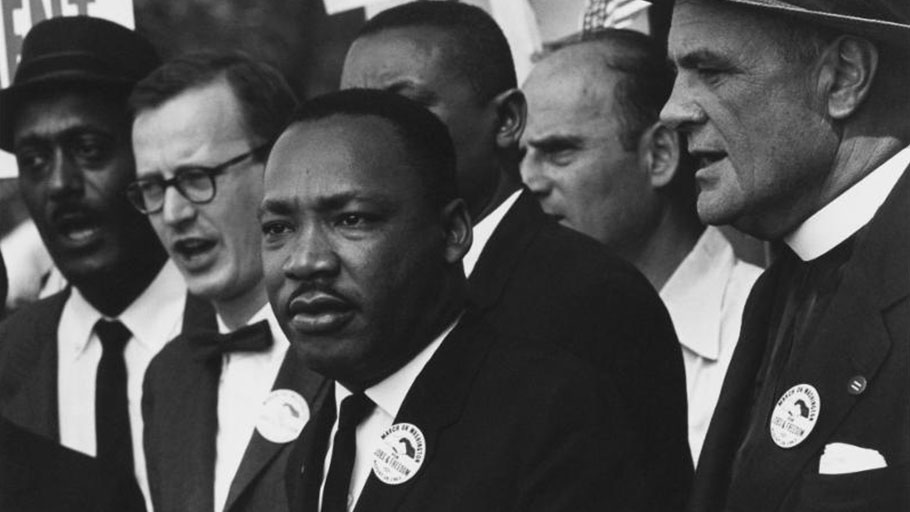

The March on Washington was actually the awakening of the ‘Poor People’s Campaign.’ Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr and his allies were going to the nation’s capital to ask America to be true to the huge promissory note that was signed years ago.

King said that, “we are coming to engage in dramatic non-violent action, to call attention to the gulf between promise and fulfilment; to make the invisible visible.” In the UK, as in America, those who have become invisible are forcing open the eyes of those who have forgotten them.

This year, 2019, marks 400 years since the first African immigrants – freedmen and indentured servants – arrived in Jamestown. The British had landed, three years earlier, having departed England as King Henry VIII had declared himself head of the new Church of England. These individuals desired a return to a simpler faith and wanted to purify the Church. However, these Puritans would use, in part, their religious system to oppress the Africans, forcing them into slavery. And, yet, these slaves would look for a saving grace from an individual depicted in the like image of their oppressor. That grace would have in it the power to forgive and mount up for civility for themselves and all of humanity.

Unlike America, the UK has no separation of church and state. In fact, 26 Bishops are in the House of Lords which includes the Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby. Recently he said that, “The burden of proof is on those that are arguing for no deal, to show that it will not harm the poorest and most vulnerable … How we care about them and how our politics affects them is a deeply moral issue.”

In the cause of bringing freedom to those invisible ones who suffer, the church has at times been oppressor and in its better moments, a harbinger of liberation. For the Puritans, the desire to establish a true Christian faith while maintaining an allegiance to the corruptive power of White supremacy, rendered their faith in fact anti-Christian. In the case of King, his commitment to Christ, the liberator and the kingdom he proclaimed, motivated his refusal to accept the unjust status quo which weighed heavily on the poor and to act for the sake of justice.

The UK looks to the legacy of William Wilberforce, the abolitionist, or the current impact of churches who care for the needy through foodbanks and debt counselling or organized homes for refugee families. Selina Stone, lecturer in political theology at St Mellitus College, asks the pertinent question: “How will churches respond in the UK and in America, to those with their backs against the wall?”

Again, I ask, how does one really love and heal a world if they don’t see their neighbour as themselves? Or in the words of Dr. King, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Keith Magee is a public intellectual with a focus on social justice and theology. He is currently senior fellow in culture and justice at University College London and is in pastoral leadership at The Berachah Church, Dorchester Centre, MA. For more information visit www.4justicesake.org or follow him on social media @keithlmagee.