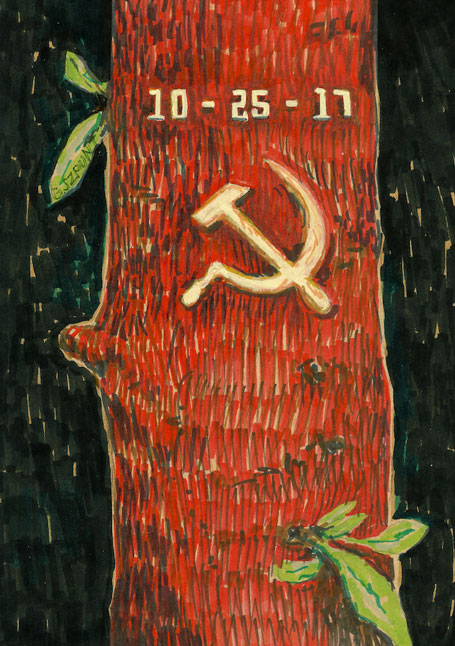

Image: A depiction of Lenin and his supporters by Vladimir Serov.

What we can learn from the triumph of the Russian Revolution and its subsequent demise.

By Pete Dolack —

History does not travel in a straight line. I won’t argue against that sentence being a cliché. Yet it is still true. If it weren’t, we wouldn’t be still debating the meaning of Russia’s 1917 October Revolution on its centenary, and more than a quarter-century after its demise.

Neither the Bolsheviks nor any other party played a direct role in the February revolution that toppled Tsar Nicholas II, for the leaders of those organizations were in exile abroad or in Siberia or in jail. Nonetheless, the tireless work of activists laid the groundwork. The Bolsheviks were a minority even among the active workers of Russia’s cities then, but later in the year, their candidates steadily gained majorities in all the working-class organizations — factory committees, unions and soviets. The slogan of “peace, bread, land” resonated powerfully.

The time had come for the working class to take power. Should they really do it? How could backward Russia, with a vast rural population still largely illiterate, possibly leap all the way to a socialist revolution? The answer was in the West: The Bolsheviks were convinced that socialist revolutions would soon sweep Europe, after which the advanced industrial countries would lend ample helping hands. The October Revolution was staked on the prospect of European revolutions, particularly in Germany.

We can’t replay the past, and counterfactuals are generally sterile exercises. History is what it is. It would be easy, and overly simplistic, to see the idea of European revolution as romantic dreaming, as many historians would like us to believe. Germany came close to a successful revolution, and likely would have done so with better leadership and without the treachery of the Social Democrats who suppressed their own rank and file in alliance with the deeply undemocratic Germany army. That alone would have profoundly changed the 20th century, and provided impetus to the uprisings going off across the continent.

The revolution survived. But the revolutionaries inherited a country in ruins, subjected to embargoes that allowed famines and epidemics to rage.

Consider the words of British Prime Minister David Lloyd George in 1919 as he discussed his fears with Georges Clemenceau, the French prime minister: “The whole of Europe is filled with the spirit of revolution. There is a deep sense not only of discontent, but of anger and revolt among the workmen against prewar conditions. The whole existing order, in its political, social and economic aspects is questioned by the masses of the population from one end of Europe to the other.”

Russia was the weak link in European capitalism, and the stresses of World War I added to the conditions for a revolution. Revolution was not inevitable. Leon Trotsky’s analogy of a steam engine comes to life here: “Without a guiding organization, the energy of the masses would dissipate like steam not enclosed in a piston-box. But nevertheless what moves things is not the piston or the box, but the steam.”

The October Revolution wouldn’t have happened without a lot of steam; without masses of people in motion working toward a goal. The revolution faced enormous problems, assuming it could withstand the counter-assault of a capitalist world determined to destroy it. It was a beacon for millions around the world, inspiring strikes and uprisings across Europe and North America. Dock and rail workers in Britain, France, Italy and the United States showed solidarity by refusing to load ships intended to be sent to support the counterrevolutionary White Armies. Those armies, assisted by 14 invading countries, massacred Russians without pity, seeking to drown the revolution in blood.

The revolution survived. But the revolutionaries inherited a country in ruins, subjected to embargoes that allowed famines and epidemics to rage. The cities emptied of the new government’s working-class base and the new nation was surrounded by hostile capitalist governments. There was one thing the Bolshevik leaders had agreed on: Revolutionary Russia could not survive without revolutions in at least some European countries, both to lend helping hands and to create a socialist bloc sufficiently large enough to survive. The October Revolution would go under if European revolution failed.

Yet here they were. What was to be done? With no road map, shattered industry, depopulated cities, and infrastructure systematically destroyed by the armies hostile to the revolution — and having endured seven years of world war and civil war — the Bolsheviks had no alternative to falling back on Russia’s own resources. Those resources included workers and peasants. For it was from them that the capital needed to rebuild the country would come, as well as to begin building an infrastructure that could put Russia on a path toward actual socialism, to make it more than an aspirational goal well in the future.

Without economic democracy, there can be no political democracy.

The debates on this, centering on the tempo of transition and how much living standards could be shortchanged to develop industry, raged through the 1920s. Russia’s isolation, the dispersal of the working class, the inability of a new working class assembled from the peasantry to assert its interests, and the centralization necessary to survive in a hostile world — all compounded by ever-tightening grasps on political power by ever-narrowing groups that flowed from the country’s isolation — would culminate in the dictatorship of Joseph Stalin.

Stalin would one day be gone, and the terror he used to maintain power gone with him. But the political superstructure remained — the single party controlling economic, political and cultural life, and the over-centralized economic system that steadily became a more significant fetter on development. The Soviet system was overdue for large-scale reforms, including giving the workers in whose name the party ruled much more say in how the factories (and the country itself) were run. Once the Soviet Union collapsed, and the country’s enterprises were put in private hands for minuscule fractions of their value, the chance to build a real democracy vanished.

A real democracy? Yes. For without economic democracy, there can be no political democracy. The capitalist world we currently inhabit testifies to that. What if the people of the Soviet Union had rallied to their own cause? What if the enterprises of that vast country had become democratized — some combination of cooperatives and state property with democratic control? That could have happened, because the economy was already in state hands. That could have happened, because a large majority of the Soviet people wanted just that. Not capitalism.

Illustration by Gabriella Szpunt

They were unable to intervene during perestroika. Nor did they realize what was in store for them once the Soviet Union was disbanded, and Boris Yeltsin could impose shock therapy that threw tens of millions into poverty and would eventually cause a 45 percent reduction in gross domestic product — much deeper than the U.S. contraction during the Great Depression.

A revolution that began with three words — peace, bread, land — and a struggle to fulfill that program ended with imposed “shock therapy” — a term denoting the forced privatization and destruction of social safety nets coined by neoliberal godfather Milton Friedman as he provided guidance to Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. Millions brought that revolution to life; three people (the leaders of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus) put an end to it in a private meeting — with the financial weapons of the capitalist powers looming in the background, ready to pounce.

The Soviet model won’t be recreated. That does not mean we have nothing to learn from it. One important lesson from revolutions that promised socialism (such as the October Revolution) and revolutions that promised a better life through a mixed economy (such as Nicaragua’s Sandinista revolution) is that a democratic economy and thus a stable political democracy have to rest on popular control of the economy — or, to use the old-fashioned term, the means of production.

Leaving most of the economy in the hands of capitalists gives them the power to destroy the economy, as Nicaragua found out in the 1980s and Venezuela is finding out today. Putting all of the enterprises in the hands of a centralized state and its bureaucracy reproduces alienation on the part of those whose work makes it run. It also puts into motion distortions and inefficiencies, because no small group of people, no matter how dedicated, can master all the knowledge necessary to make the vast array of decisions that make it work smoothly.

The world of 2017 is different from the world of 1917. For one, the looming environmental and global-warming crisis of today gives us additional impetus to transcend the capitalist system. Unlike a century ago, we need to produce and consume less, not more. We need the participation of everyone, not bureaucracy, and planning from below with flexibility, not rigid planning imposed from above. But we need also learn from the many advances of the 20th century’s revolutions — the ideals of full employment, culture available for everyone, affordable housing and health care as human rights and dignified retirement, and the notion that human beings exploiting and stunting the development of other human beings for personal gain is an affront.

The march forward of human history is not a gift from gods above nor a present handed us by benevolent rulers, governments, institutions or markets. It is the product of collective human struggle on the ground. If revolutions fall short or fail, that simply means the time has come to try again and do it better.

Pete Dolack is the author of It’s Not Over: Learning From the Socialist Experiment(Zero Books, 2016), which includes a study of the Russian and German revolutions after World War I and the development and fall of the Soviet Union, with a focus on retrieving this history for emerging and future movements that seek to overcome the political and economic crises of today.